|

The

foundering of the hopes of Greek participation at the Dardanelles after Admiral

Kerr’s discouraging report of 9 September 1914 seemed, for the moment, to

spell the end of any Allied attempt to force the Straits. Although one of the

earliest dispatches to mention the possibility of forcing the Dardanelles

(Ambassador Mallet’s telegram of 18 August)

referred only to the fleet, by September Churchill had received opinions from

various naval and military sources on the spot – Kerr, Limpus, Cunliffe-Owen

– all of whom agreed that any attempt must be accompanied by military

operations. Churchill himself was later to argue that, at the time, he no longer

considered the forcing of the Straits by ships alone a practicable proposition;

yet this is precisely what he subsequently attempted to do. Although the saga of

the ‘drift to the Dardanelles’ has been told before, new evidence, never

before used, now makes it possible to offer an alternative interpretation in

which Churchill’s main aim, initially, was to humour Fisher and so prevent his

resignation at a critical juncture; and in which information about Goeben

plays a far greater part than previously acknowledged.

There is no doubt that the Dardanelles was one obvious place at which to

assault the Turks; but it was not the only one. When emphasizing the dangers on

27 August 1914 Cunliffe-Owen, the British Military Attaché in Constantinople,

advocated operations in the Persian Gulf or Syria, ‘where Turkish forces are

almost negligible.’ What then were the attractions of the Dardanelles? For

Churchill, who ascribed to the commonly held belief that, by cutting out the

heart – Constantinople – the extremities would soon die, they were fourfold:

first, the Straits offered the quickest route by which the Turkish capital could

be threatened; second, any proposed operations re-opened the possibility of

bringing Greece in; third, the fact that the navy would be involved prominently;

and, lastly and more speculatively, it was the shortest distance to reach and

attack Goeben. This last point should

not be overlooked: as punishment for making the First Lord look a fool the Turks

were subjected to the fatuous bombardment of the Dardanelles forts in early

November. By then the prospect of Greek aid had withered and Goeben

was busy in the Black Sea. Churchill might have written off Turkey (despite his

speculative statement to Asquith on the last day of 1914 that he had wanted

Gallipoli attacked on the Turkish declaration of war)

had it not been for a lucky shot from one of Carden’s ships. In evidence at

the Dardanelles Commission Churchill later stated:

It

is obvious that the ideal action against Turkey if she came into the War, was at

the earliest possible moment to seize the Gallipoli Peninsula by an amphibious

surprise attack and to pass a fleet into the [Sea of] Marmora …When at the end

of August I formed the opinion that our diplomacy would fail to keep Turkey from

joining our enemies, I immediately began to make enquiries from the War Office

about the possibility of such an operation…I was perfectly well aware that the

right and obvious method of putting a British fleet into the Marmora was by an

amphibious attack on the Gallipoli Peninsula. This view was general at the

Admiralty — all my advisers shared it. Indeed it was so obvious, that it

scarcely needed discussion, but for this an army was wanted, and no army was

forthcoming…Like

most other people, I had held the opinion that the days of forcing the

Dardanelles were over; and I had even recorded this opinion in a Cabinet paper

in 1911. But this war had brought many surprises. We had seen fortresses reputed

throughout Europe to be impregnable collapsing after a few days’ attack by

field armies without a regular siege…

Furthermore,

whatever else he may subsequently have said, when asked at the Commission

hearings to explain the object of the November bombardment, Churchill answered

that, as far as he could recollect, it ‘was to see what the effect of the

ships’ guns would be on the outer forts — whether they would injure them.’

How much importance, Churchill was then asked, did he attach to what had

happened at Liége and Antwerp? The then former First Lord, who had come in for

much criticism as a result of his forlorn attempt to hold Antwerp in October

1914 at the head of the half-trained Royal Naval Division, replied, ‘Certainly

the destruction of the first class fortresses in a few days by the fire of heavy

howitzers was a great and surprising fact.’ Churchill also maintained that a

gunnery expert at the Admiralty had examined the effect of artillery fire

against the forts.

The destruction of Fort Sedd-el-Bahr on 3 November had a rousing effect

not only on those who witnessed it, but also in London.

Churchill promptly began to press Admiral Carden for further ways of injuring

the enemy; the Admiral could only suggest another bombardment, to which

Churchill concurred on 16 November before, apparently, being dissuaded by

Admiral Oliver who was concerned that the ships’ guns might not have enough

life remaining to use full charges.

A week later, at what became the first meeting of the ‘War Council’

following Asquith’s desire to have ‘a small conclave on the Naval and

Military situation’,

Churchill’s advocacy of the Dardanelles operation was confined to proposing a

feint to relieve pressure on Egypt in case of a Turkish attack. An attack on the

Gallipoli Peninsula, he admitted then, ‘was a very difficult operation

requiring a large force.’

Yet, less than a fortnight later, Asquith confessed privately that Winston’s

‘volatile mind is at present set on Turkey & Bulgaria, & he wants to

organise a heroic adventure against Gallipoli and the Dardanelles: to which I am

altogether opposed.’

What had happened?

In truth it is hard to see: Churchill had blown hot and cold on the issue

since the start of the war. His attempts to initiate planning for an attack

early in September fell foul of a lack of enthusiasm at the War Office

and the internal struggles in Athens. Equally, his bizarre scheme to ship 50,000

Russians from Archangel or Vladivostock to Gallipoli, was quickly discounted.

Then, in October, following the receipt of a further appraisal from Cunliffe-Owen,

in which the Military Attaché deprecated naval action alone, General Callwell,

the D.M.O. (according to his memoirs) outlined the dangers in a meeting with

Churchill and Fisher.

The preliminary bombardment of 3 November was borne as much out of frustration

as for any other motive. It would not be until three days after Asquith’s

comment above that Sturdee’s victory at the Falkland Islands on 8 December

removed the last major German surface threat from the seas, leaving only such

minor units as Dresden and Konigsberg to

be dealt with. This, in turn, freed a number of British ships which were not

necessarily required in the North Sea and now lacked a rôle. Nevertheless, it

was clear to Churchill at this time that troops would not be available to

participate in any Gallipoli operations,

and besides, as he admitted to Fisher when congratulating the Admiral after the

Falkland Islands’ victory, ‘I am shy of landings under fire — unless there

is no other way.’

Perhaps it was simply the case that, having mentioned the option of a

Dardanelles attack, and having appreciated the difficulty involved, Churchill

then set to work to overcome that difficulty.

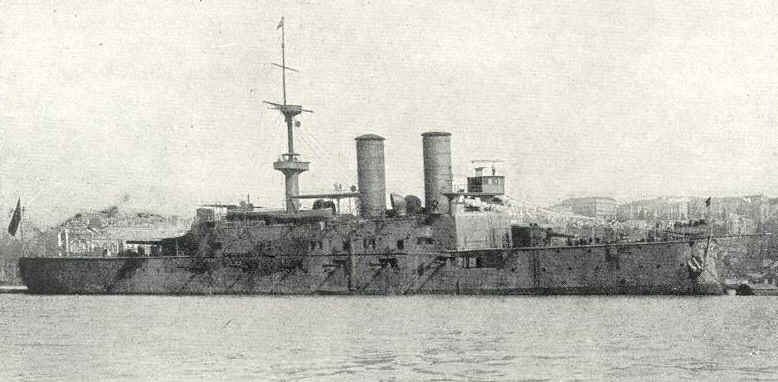

The Turkish cruiser Messudieh

Shortly after, however, a number of events conspired to persuade

Churchill that a method might be possible. Early on the morning of Sunday 13

December 1914 the British submarine B.11, commanded by Lieutenant Norman

Holbrook, set off up the Straits ‘with a view to reaching Tchanak, if

possible, and torpedoing the Lily Rickmers

[on which German staff officers were believed to be living] or any other hostile

vessel as opportunity might offer.’ B.11, which had been selected for the

hazardous attempt as her batteries had been renewed more recently that the other

submarines, was fitted with special guards projecting from her side designed to

throw clear ‘mooring wires of mines, or other obstructions likely to foul the

boat.’ At 9.40 a.m. Holbrook sighted ‘a large 2-funnelled vessel painted

grey’ which he soon ascertained was flying the Turkish ensign; thirteen

minutes later he fired one torpedo at the target which turned over and sank

within ten minutes. It was the cruiser Messudieh.

Believing the attack presaged a general Anglo-French attempt to force the

Dardanelles, reinforcements and German technical officers were rushed from

Constantinople, including Admiral von Usedom who spent ‘8 useless days

waiting’ before returning to the capital in time for Christmas.

Holbrook’s exploit demonstrated what could be done; then, three days later, a

confidential report was received in the Admiralty from Constantinople. According

to this the Turkish fleet, including Goeben,

had come off badly after an encounter with the Russian Black Sea fleet:

the after guns of the battle cruiser had been put out of action, her stern was

riddled with shell and she had four large holes in her starboard side;

casualties had been heavy and 80 of her crew were known to have been buried in

the German Embassy grounds at Therapia. More important than this, it was

reported that on 4 December what was described as a ‘slight mutiny’ had

broken out on board a Turkish ship after the German officers had received their

salary but the Turkish crew had not; Breslau

had to be summoned to stand nearby, ready to open fire if necessary to quell the

mutiny.

Then, beginning on the evening of 18 December, an entertaining charade

was played out in the Gulf of Alexandretta by the crew of HMS Doris, under Captain Larken. Ordered to attempt to interrupt the

flow of material along the Hejaz Railway which, just north of Alexandretta, ran

by the sea Larken put a party ashore that, undetected, cut the telegraph and

loosened some rails resulting in the derailment of a south-bound train. On the

following afternoon, guided by the 1907 Hague Convention, Larken delivered an

ultimatum demanding the surrender of all engines and military equipment in the

town under threat of bombardment. The reply, in the name of Djemal Pasha who had

been transferred from Constantinople to Syria as Commander-in-Chief, threatened,

in return, reprisals against British subjects held in detention. Larken warned

that such behaviour would be punished by the victorious allies at the end of the

war. In the meantime another landing party had destroyed a railway bridge,

effectively stopping all traffic. By the morning of the 22nd Larken’s

ultimatum had been accepted — but not before the Turks had removed everything

of military value from the town except two locomotives which the deputy governor

was quite prepared to destroy provided the British supplied the dynamite! Larken

thereupon sent a party ashore, under the command of the Torpedo Lieutenant,

armed with gun-cotton which could not be entrusted to the Turks. The Governor

relented and allowed the party to lay the charges but, he maintained, Turkish

dignity would only be assuaged if a Turkish officer fired the charges. The

stalemate which ensued was only broken after some hours by formally inducting

the Torpedo Lieutenant into the Turkish service for the rest of the day, at

which the engines finally met their fate.

Holbrook, Larken and the intelligence report all combined to make the

Turks appear a less than formidable enemy.

At the same time the stalemate on the Western Front – which already seemed

certain to descend into a long, bloody war of attrition – led to certain key

members of the War Council considering alternative strategies which were then

worked up into memoranda; finally, acting as the catalyst, came an appeal from

the supposedly hard-pressed Russians. The momentum had begun. On Christmas Day

1914, in an attempt to clear his own mind, Maurice Hankey, the Secretary of the

War Council, began to compose his memorandum; although not complete until the

28th, it became known as the Boxing Day

Memorandum. When finished, Hankey ‘rather fancied the result’ of his

effort and showed it to Callwell at the War Office and Oliver at the Admiralty,

both of whom proffered criticisms. Then it went to Admiral Fisher and General

Sir James Wolfe Murray, both members of the War Council; from there it went to

both Churchill and Kitchener and, eventually, Asquith.

Independently both Churchill and Lloyd George also committed their thoughts to

paper.

The spectre that drove them all was simple: ‘I agree, and I fear that

everybody must agree,’ Arthur Balfour informed Hankey, ‘that the notion of

driving the Germans back from the West of Belgium to the Rhine by successfully

assaulting and capturing one line of trenches after another seems a very

hopeless affair.’

Aware that great forces – the new armies then being raised and trained –

would become available by March 1915, Hankey looked for some other outlet for

their effective employment. To circumvent the impasse on the Western front

Hankey investigated two methods: either some new invention which would give the

Allies the upper hand, or else an attack at a subsidiary point which would

compel the enemy ‘so to weaken his forces that an advance becomes possible’

against his main forces. Of the former, Hankey put forward a number of

suggestions — the development of large, heavy, motorized rollers driven by a

caterpillar which would crush the barbed wire and allow troops to advance in its

wake; bullet proof shields or armour; grapnels powered by rockets to snare the

enemy barbed wire; and a special pump or catapult to throw oil or petrol into

enemy trenches.

Turning to his second method, the subsidiary attack, Hankey was forced to

admit that ‘the great Russian diversion has not proved sufficiently powerful

to cause the enemy to denude his forces on the western front to a dangerous

extent’, while the ‘greatest asset’ Britain possessed in the war – the

ability to exert economic pressure – was not only slow to operate but was

hindered by the enormous trade Holland and Denmark were conducting with Germany.

‘Germany can perhaps be struck most effectively and with the most lasting

results on the peace of the world’, Hankey argued, ‘through her allies, and

particularly through Turkey.’ Turkey would be the perfect illustration that

any country choosing to ally herself with Germany against the ‘great sea

power’ would be doomed to disaster; this would be a salutary object lesson for

the Balkan states in trying to overcome their mutual distrust. Hankey continued:

…21.

But supposing Great Britain, France, and Russia, instead of merely inciting

these races to attack Turkey and Austria were themselves to participate actively

in the campaign, and to guarantee to each nation concerned that fair play should

be rendered. If the whole of the Balkan States were to combine there should be

no difficulty in securing a port on the Adriatic, with Bosnia and Herzegovina,

and part of Albania, for Servia; Epirus, Southern Albania, and the islands, for

Greece; and Thrace for Bulgaria. The difficult Dardanelles question might

perhaps be solved by allowing more than one nation to occupy the north side and

by leaving Turkey on the south, the Straits being neutralised.

22.

If Bulgaria, guaranteed by the active participation of the three Great Powers,

could be induced to co-operate, there ought to be no insuperable obstacle to the

occupation of Constantinople, the Dardanelles, and Bosphorus. This would be of

great advantage to the allies, restoring communication with the Black Sea,

bringing down at once the price of wheat, and setting free the much-needed

shipping locked up there.

23.

It is presumed that in a few months time we could, without endangering the

position in France, devote three army corps, including one original first line

army corps, to a campaign in Turkey, though sea transport might prove a

difficulty. This force, in conjunction with Greece and Bulgaria, ought to be

sufficient to capture Constantinople.

24.

If Russia, contenting herself with holding the German forces on an entrenched

line, could simultaneously combine with Servia and Roumania in an advance into

Hungary, the complete downfall of Austria-Hungary could simultaneously be

secured.

25.

Failing the above ambitious project, an attack in Syria would prove a severe

blow to Turkey, particularly if combined with an advance from Basra to Bagdad by

a reinforced army.

The

insuperable problem with Hankey’s ‘ambitious project’ remained the

difficulty of getting the Balkan States to act in concert.

Hankey also tacitly admitted that the war would end in stalemate so that,

‘Failing the invasion of Germany itself, which, in accordance with correct

strategical principle, has hitherto been our aim, it is suggested that we should

endeavour by the means proposed to get assets into our hands wherewith to

supplement the tremendous asset of sea power and its resultant economic

pressure, wherewith to ensure favourable terms of peace when the enemy has had

enough of the war.’

Churchill’s memorandum took the form of a letter to Asquith on 29

December in which he posed the same question as Hankey: with the Allies’

growing military power ‘Are there not other alternatives than sending our

armies to chew barbed wire in Flanders? Further, cannot the power of the Navy be

brought more directly to bear upon the enemy? If it is impossible or unduly

costly to pierce the German lines on existing fronts, ought we not, as new

forces come to hand, to engage him on new frontiers, and enable the Russians to

do so too?’ As opposed to Hankey, however, Churchill’s suggestion for a

flanking operation involved Britain gaining command of the Baltic after first

having invaded Schleswig-Holstein and forced the accession of Denmark to the

allies. This, in turn, depended upon the capture of an advanced base for which

purposes, Churchill argued, the island of Borkum was ideal.

The Baltic scheme had long been a pet project of Fisher’s,

but now Churchill discovered that his First Sea Lord had gone cool on the idea

— in almost daily contact with Jellicoe, Fisher had become imbued with the

latter’s caution,

while complaining at the same time of Churchill’s monopoly of the initiative

and threatening, vaguely, about having to clear out.

Besides, Fisher was already aware of the great flaw in the scheme. On 14

December, over lunch in the Admiralty, Fisher had informed Sir Julian Corbett,

the naval historian, of his Baltic proposals and, five days later, Corbett

forwarded a memorandum on the subject. A cardinal feature of the scheme was that

the whole of the battle fleet would be required, which would then leave the

North Sea denuded. To overcome this, it was proposed to ‘sow the North Sea

with mines on such a scale that naval operations in it would become

impossible.’

As Corbett pointed out in an accompanying letter:

I

have endeavoured to state your case for the Baltic as well as I can — setting

out such objections as occurred to me and meeting them — to show the

difficulties had been considered. There is one — unfortunately rather obvious

— objection which I have not mentioned because I don’t see how to meet it.

It is this — if it is possible for us to make the North Sea untenable with

mines, is it not even more possible for the Germans to play the same game in the

Baltic? Perhaps you can see a way of meeting this — it is sure to be taken by

those who have no stomach for your plan.

Fisher

therefore knew, by the end of December, that the game was up as far as his

version of the Baltic scheme was concerned. Churchill later maintained that,

although

the First Sea Lord’s strategic conceptions were centred in the entry of the

Baltic, and although he was in principle favourable to the seizure of Borkum as

a preliminary, I did not find in him that practical, constructive and devising

energy which in other periods of his career and at this period on other subjects

he had so abundantly shown. I do not think he ever saw his way clearly through

the great decisive and hazardous steps which were necessary for the success of

the operation. He spoke a great deal about Borkum, its importance and its

difficulties; but he did not give that strong professional impulsion to the

staffs necessary to secure the thorough exploration of the plan. Instead, he

talked in general terms about making the North Sea impassable by sowing mines

broadcast and thus preventing the Germans from entering it while the main

strength of the British Fleet was concentrated in the Baltic. I could not feel

any conviction that this would give us the necessary security…Therefore, while

the First Sea Lord continued to advocate in general terms the entry of the

Baltic, I persistently endeavoured to concentrate attention upon the practical

steps necessary to storm and seize the island of Borkum, and thus either block

in the German Fleet or bring it out to battle…

Fisher,

having become only too aware of the suicidal nature of the Baltic scheme, and

despite Corbett’s reservations, had put forward the mining counter-proposal in

an attempt to divert Churchill. However, as Jellicoe later admitted, ‘We had

not a hundredth part of the mines necessary for such a scheme’.

Exasperated, Churchill patiently informed Fisher on 22 December that ‘You must

take an island and block them in, à la

Wilson; or you must break the [Kiel] canal locks, or you must cripple their

Fleet in a general action. No scattering of mines will be any substitute for

these alternatives. The Baltic is the only

theatre in which naval action can appreciably shorten the war. Denmark must

come, and the Russians be let loose on Berlin.’ There would be, Churchill

added plaintively, four good Russian dreadnoughts to assist.

On the morning of 29 December Hankey had a twenty minute talk with

Fisher, who complained that both Churchill and the C.O.S., Admiral Oliver, were

so strongly opposed to the mining operation that he could do nothing. Fisher

therefore asked Hankey ‘to write something on the subject’ — however, not

only did Hankey not wish to intervene ‘in so domestic an Admiralty

question’, he had, of course, just completed his own strategical analysis.

In any event, Admiral Oliver, who had seen Hankey’s memorandum in draft, soon

became a convert to his cause after having been dismayed by the discussions of

strategy at the Admiralty. Churchill, Oliver declared, wanted to capture Borkum

and Emden; Fisher to send the Grand Fleet into the Baltic to convey a Russian

Army from Petrograd to land on the Pomeranian coast and march on Berlin; Wilson

to bombard Heligoland with pre-Dreadnoughts prior to capturing it. ‘I hated

all these projects’, Oliver later admitted, ‘but had to be careful what I

said. The saving clause was that two of the three were always violently opposed

to the plan of the third under discussion.’

‘There are three phases of the naval war,’ Churchill had informed

Asquith on 29 December: ‘first the clearance of the seas and the recall of the

foreign squadrons, that is nearly completed; second, the closing of the Elbe —

that we have now to do; and third, the domination of the Baltic — that would be decisive.’ The First Lord also pointedly referred to

the difficulties involved in co-operation between the Admiralty and War Office

of which Asquith was ‘fully aware’.

The Prime Minister received ‘the very interesting memoranda’ of Churchill

and Hankey on 30 December. ‘There is here’, he wrote to Venetia Stanley

while on the train to London to attend a Cabinet, ‘a good deal of food for

thought. I am profoundly dissatisfied with the immediate prospect — an

enormous waste of life & money day after day with no appreciable

progress…I don’t see the way to a decisive change before March, but I am

sure that we ought to begin at once to devise, in consultation with the French

& the Russians, a diversion on a great & effective scale.’

By the following day Churchill had seen Hankey’s memorandum and discussed it

with him, finding that they were ‘substantially in agreement and our

conclusions are not incompatible.’ Nevertheless, although admitting that he

had always favoured an attack on Gallipoli, Churchill spent the rest of the day

composing a justification for the Borkum operation.

Lloyd George had also been busy. In a memorandum as wide-ranging as

Hankey’s, the Chancellor attempted to reconcile the stalemate on the western

front with what, he admitted, was the political and military necessity of

‘winning a definite victory somewhere’. Labelling the Baltic Scheme (‘This

proposal is associated with the name of Lord Fisher’) as being ‘very

hazardous’ he proposed instead two independent operations ‘which would have

the common purpose of bringing Germany down by the process of knocking the props

under her.’ It was typical of the man that Lloyd George had been seduced by

this common fallacy as, far from being props, the German satellites were instead

a drain on her resources; unaware of this, he advocated an attack upon Austria,

in conjunction with the Serbs, Greeks and Roumanians, combined with an attack on

Turkey. For the latter, Lloyd George isolated a number of conditions that would

have to be fulfilled: the force employed should not be so large as to weaken the

offensive in the main theatre; lines of communication should be short to

conserve troops, which necessitated an attack near the sea; conversely Turkish

lines of supply should be made as long as possible; there should be a chance of

winning a dramatic victory; and ‘it would be a great advantage from this point

of view if it were in territory which appeals to the imagination of the people

as a whole.’ Lloyd George was aware of the latest intelligence which indicated

that the Turks had amassed a force of 80,000 troops in Syria ready to march upon

the Suez Canal. He suggested therefore that once the Turks had entangled

themselves in this venture, a force of 100,000 allied troops should be landed in

Syria, behind the Turkish Army, to cut it off: ‘A force of 80,000 Turks would

be wiped out and the whole of Syria would fall into our hands.’ The Chancellor

did not speculate on what view the French might take of such a scheme.

Asquith was impressed with this memorandum — so impressed he decided to

take it, along with Churchill’s ‘Baltic’ memorandum, to Venetia Stanley to

‘talk it all over’ with his paramour. Almost incidentally it would seem, he

decided to summon the War Council for Thursday 7 and Friday 8 January to review

the situation.

Nothing could better epitomize the higher conduct of the war under Asquith’s

tutelage. Churchill had argued, rightly, on 31 December, that the issues to be

decided were so important that the War Council should meet daily ‘for a few

days next week. No topic can be pursued to any fruitful result at weekly

intervals.’

Yet, while Asquith agreed to convene the War Council for two consecutive days,

he seemed more pleased that this would necessitate his return to London from

Kent, where he had been staying; he would, therefore, be near to Miss Stanley

for most of the week, as there was also a Cabinet scheduled for the Wednesday.

‘I love the prospect’, he wrote, ‘for I shall be in close touch with my

dearest & wisest counsellor.’

Hankey, keen to recruit allies to his cause, sent Balfour his

‘invitation’ to the meetings on 2 January. ‘I think’, he enthused,

‘the discussion will be of great importance’, adding,

I

find that there is a very general feeling that we must find some new plan of

hitting Germany. You have already received my own ideas on the subject. The

First Lord has also written a paper or a letter to the P.M. pressing his own

favourite plan with some important extensions. Mr Lloyd George has also written

to the P.M. urging developments, — rather on my lines, I gather. Meanwhile my

information is that Italy and Greece are rather cooling down. It seems to me

that we ought first to make up our own minds & then to invite our allies to

a round table conference. I am fairly certain that the Prime Minister means to

ventilate the various proposals at Thursday’s meeting, with a view to making

up the Government’s mind, so I feel sure that you will think it worth while to

attend…

As

the time approached in London for a decision to be made, another fillip to the

growing clamour for operations in the East was provided by events in Russia. On

30 December 1914 the head of the British Military Mission in Russia,

Major-General Sir John Hanbury-Williams, was summoned by the Grand Duke Nicholas

and informed that the situation in the Caucasus was serious; the Turks, having

pushed back the initial Russian advance in November, now stood poised with an

army of 100,000. The Russian C-in-C requested ‘help by a demonstration of some

kind which would alarm the Turks, and thus ease the position of the Russians on

the Caucasus front.’ Williams, with a ‘pretty shrewd idea’ that ‘our

armies were not yet strong enough to spare sufficient men for a military

expedition’, asked instead if a naval demonstration would be of any use. When

the Grand Duke ‘jumped at it gladly’

the General went immediately to Sir George Buchanan who telegraphed Grey on New

Year’s Day, 1915. The Turks, Buchanan explained, had commenced an enveloping

movement and the Russian commander in the field was pressing most urgently for

reinforcements, a plea the Grand Duke was forced, for the moment, to resist as

he was ‘determined to proceed with his present plans against Germany and keep

them unaltered.’

As Grey’s paramount aim was to keep the Germans pinned down in the East, the

implications of Buchanan’s report became frighteningly apparent — a serious

reverse against the Turks might compel the Russians to weaken the Allies’

Eastern front by diverting troops to the Caucasus, especially the Fourth

Siberian Army Corps which was on its way to Warsaw but which, Grey was warned,

‘in ordinary course it would be natural to send…to Turkish front.’

The enveloping movement mentioned by Buchanan had commenced on 21

December when Enver himself took command of the Third Army with the intention of

cutting the Russian line of communication to their main base at Kars, before

taking Kars itself, then Ardahan and Batum, as a preliminary to a full scale

invasion of the Caucasus. The key position was Sarikamish; by 26 December, in

appalling weather conditions, the Turks had managed to occupy the town. Victory

was almost theirs until Enver attempted one manoeuvre too many, a wheeling

movement in the teeth of a blizzard which gave the Russians the chance to

counter-attack. In the ensuing battle almost a third of the Turkish force froze

to death; only 12,000 men (including, inevitably, Enver himself) managed to

escape. The danger to the Russian army had been obliterated in the snow, but

this information was not available in Petrograd when the Grand Duke made his

appeal to General Hanbury-Williams.

There was even a suggestion that the Grand Duke’s appeal was designed more to

excuse the inability of the Russians to attack on the Eastern Front.

Kitchener and Churchill both became aware of Buchanan’s telegram on

Saturday, 2 January. Later that day Kitchener saw Churchill at the Admiralty to

ascertain whether the Navy could do anything to help. Churchill subsequently

maintained that ‘All the possible alternatives in the Turkish theatre were

mentioned …We both saw clearly the far-reaching consequences of a successful

attack upon Constantinople. If there was any prospect of a serious attempt to

force the Straits of the Dardanelles at a later stage, it would be in the

highest degree improvident to stir them up for the sake of a mere

demonstration…’

Churchill then put forward various options – a demonstration at Smyrna or

Alexandretta or the Syrian coast – but Kitchener demurred, arguing that troops

could not be found. Kitchener then returned to his lair;

meanwhile, Churchill consulted his advisers at the Admiralty who, presumably,

had little more to offer.

Having confirmed at the War Office that troops could not be spared, Kitchener

thereupon penned a pessimistic note to Churchill:

I

do not see that we can do anything that will seriously help the Russians in the

Caucasus. The Turks are evidently withdrawing most of their troops from

Adrianople and using them to reinforce their army against Russia probably

sending them by the Black sea. In the Caucasus and Northern Persia the Russians

are in a bad way. We have no troops to land anywhere. A demonstration at Smyrna

would do no good and probably cause the slaughter of Christians. Alexandretta

has already been tried and would have no great effect a second time.

The coast of Syria would have no effect. The only place that a demonstration

might have some effect in stopping reinforcements going East would be the

Dardanelles — particularly if as the Grand Duke says reports could be spread

at the same time that Constantinople was threatened. We shall not be ready for

anything big for some months.

Kitchener

also wrote the same day to Sir John French of the feeling gaining ground in

London that, while it was essential to defend the line in the West, surplus

troops could be better employed elsewhere; the question remained, where to exert

this additional pressure? Russia, Kitchener reported prematurely, was hard

pressed in the Caucasus and only just holding her own in Poland.

In writing so, Kitchener was presumably only too well aware of what

French’s reaction would be — that troops could not be spared, which would,

of course, support the assertion that Kitchener had just made to Churchill.

French duly swallowed the bait and replied in the expected fashion: ‘the

impossibility of breaking through the German line’, he declared vigorously,

‘is not by any means admitted.’ It was largely a question of the sufficient

expenditure of high explosive ammunition: ‘Until the impossibility of

effective action in France and Flanders is fully proved, there can be no

question of employing British or French troops elsewhere.’ French was also

dismissive of operations in Gallipoli, Asia Minor or Syria: ‘Any attack on

Turkey would be devoid of decisive result. In the most favourable circumstances

it could only cause the relaxation of the pressure against Russia in the

Caucasus and enable her to transfer two or three Corps to the West, a result

quite incommensurate with the effort involved. To attack Turkey would be to play

the German game, & to bring about the end which Germany had in mind when she

induced Turkey to join in the war, namely, to draw off troops from the decisive

spot which is Germany herself.’ In the margin of this letter French added,

correctly, that the latest reports indicated the Russians were now not

unduly harassed in the Caucasus.

This was confirmed by Hanbury-Williams, who wrote to Kitchener on 3 January that

he had called at the Russian War Office the previous day and found that ‘the

position in Caucasus is at present somewhat better & the immediate danger of

a bad reverse there seems to have passed.’ Nevertheless, he added

conscientiously if fatefully, ‘they will, I know, be much relieved if the

Turkish pressure can be eased a bit.’

|