|

Although

the Germans have reason to be well satisfied with the remarkable results of the

presence of Goeben in this port, yet

they have not achieved their main object which was and is the outbreak of war

between Turkey and Great Britain & Russia. Another object is to achieve a

protectorate by peaceful penetration which they have really achieved. It is

extraordinarily difficult to know what is going on and I feel sometimes

bewildered by the maze of lies and wild rumours which reach me every hour of the

day. The most circumstantial reports based apparently upon unimpeachable

evidence are flatly contradicted by equally circumstantial reports based upon

similar evidence. It is quite impossible to believe anything at all, whatever

the authority, and one has to fall back on probabilities relying on one’s own

judgment & forming one’s impressions.

Turkish troops listening to the proclamation of a Jihad

With

regard to his many conversations with the Grand Vizier, Mallet was convinced

that Said Halim ‘knows that the situation of the [Ottoman] Empire is desperate

— that bankruptcy is not coming but already there, that the people are worn

out with 3 years of war and unrest and with the prospect of another war with

they know not whom, simply to gratify the vanity of a fatuous young idiot like

Enver & a mad German general like Liman.’

Despite all the evidence to the contrary Mallet still could not give up hope

that ‘if we still continue to exercise patience and if we still have successes

as I do not doubt, we may pull it off, and that although we are at the mercy of

an incident, it is not I but Wangenheim who will have to leave first. I confess

that I should hate to be beaten now by Wangenheim, who is a typically

unscrupulous and contemptible form of Teuton.’ And, as far as the Straits were

concerned, ‘It will be impossible’, Mallet contended, ‘to allow this gate

on a great highway to be in the hands of a set of epileptic lunatics for

ever.’

On the day he wrote this, Mallet learned from a Greek source that

extremists were allegedly plotting to assassinate him within four days. As a

precaution he remained in the Embassy on the 17th, venturing out only briefly to

see Giers who advised him not to attend the memorial service to be held the

following day for King Carol of Roumania. Whether or not there was a plot afoot

his circumspection was rewarded, for Mallet was still alive on the fourth day.

No sooner had he thwarted the conspirators than Mallet heard of a planned armed

demonstration against the Embassy: to counter this he borrowed Lord Gerald

Wellesley’s motor and had it sent to collect the rifles kept in store for such

an eventuality. Once more the attack did not materialize and, much to the

annoyance of Lord Gerald, the upholstery on his car was badly stained by the oil

smeared on the rifles.

The death of King Carol

– an ardent supporter of Austria – had upset perceptions as to the alignment

of Roumania which, it was now thought, would gravitate towards the Entente. If

the pendulum had begun to swing towards continuing neutrality, the arrival of

the first shipment of German gold on 16 October, and the apparently unequivocal

conversion of Talaat and Djemal to intervention, sealed the fate of the Ottoman

Empire. On 22 October Enver presented the Germans with his war plans. The War

Minister maintained that, due to the continued uncertainty in the Balkans,

substantial Turkish forces would have to remain in Thrace. The options that

remained were, in the main, those that had been canvassed in the preceding

months: the proclamation of a jihad

against the Entente; the dispatch of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (though

this would take some time); diversionary operations against Russian land forces

in the Caucasus; seek out and attack the Russian Black Sea Fleet. Of the four

options, only the last promised immediate results; the plans were unhesitatingly

approved by the Germans. One final hurdle remained for Enver. Now, at the last

minute, Halil and Talaat began to waver. There was even talk of Halil and Hafiz

going to Berlin to plead for another six months’ neutrality as Turkish arms

remained inadequate for the task.

It was too late. Enver promptly resorted to subterfuge by handing Souchon a

sealed order to commence hostilities against Russia without a formal declaration

of war. If, however, Enver found that he could not persuade his colleagues to

acquiesce in such a radical course the Minister for War would instruct Souchon not

to open the orders — this was to be the pre-arranged signal that, to force the

issue, Souchon himself would have to manufacture an incident. Wangenheim,

however, was not at all satisfied with this arrangement.

On 23 October the Ambassador sent the Commander of the German Naval Base, Humann,

to see Enver who, typically, was not in his office. Humann thereupon dictated a

note to Colonel Kiazim Bey, Enver’s A.D.C.:

German

Ambassador is of opinion that Fleet Commander Admiral Souchon must have in his

hands a written declaration from Enver Pasha if Souchon is to carry out

Enver’s plan to cause Russian incident. Otherwise, in case of military failure

or political defeat for Enver, a grave compromise of German policy with

extremely fatal consequences is inevitable.

Enver’s

subterfuge had been designed to override opposition from his own side and did

not take into account Wangenheim’s last-minute faint-heartedness. In the

circumstances, there was little that Enver could do but comply, which he did two

days later:

War

Minister Enver Pasha to Admiral Souchon

October 25, 1914

The

entire fleet should manoeuvre in Black Sea. When you find a favourable

opportunity, attack the Russian fleet. Before initiating hostilities, open my

secret order personally given you this morning. To prevent transport of material

to Serbia, act as already agreed upon. Enver Pasha.

[Secret order] The Turkish fleet should gain mastery of Black Sea by

force. Seek out the Russian fleet and attack her wherever you find her without

declaration of war. Enver Pasha.

Wangenheim,

too, had some final instructions for Souchon: ‘(1) put to sea immediately, (2)

no aimlessness, but war by all means, (3) if possible, report soon to Berlin on

operative intentions.’

Souchon now had a surprise for Enver. Rather than an incident at sea, the

Admiral had determined upon the far more provocative scheme of attacking the

Russian coast! On that afternoon the German officers began to leave the

congenial environment of the steamship General

to rejoin their ships, German or Turkish, which were congregated around Goeben.

Aboard Breslau orders were issued to set out for the Black Sea for scouting

practice; Lieutenant Dönitz later recorded that word had been received that the

Russians were sowing mines at the entrance to the Bosphorus and that Souchon

planned to cut off their retreat!

In reality the plan was for a simultaneous attack at four locations –

Sebastopol, Theodosia, Novorossisk and Odessa – early on the morning of 29

October. Goeben, accompanied by two torpedo boats and a gun boat, would go to

Sebastopol; the targets for Breslau

(accompanied by Berk) and Hamidieh

would be Novorossisk and Theodosia respectively; while Odessa would be attacked

by three torpedo boats. The fleet sailed on the evening of 27 October. One of

the torpedo boats detailed for Odessa developed engine trouble and turned back;

the remaining two (Muavenet and Gairet) sighted the lights of Odessa at 3 a.m. on the 29th. On a

moonless night the boats were unsure as to how to enter the harbour when,

fortuitously, three steamers emerged, the first showing lights. The Turkish

vessels quickly ran past the emerging ships, into the harbour and, from about 70

yards, put a torpedo into the Russian gunboat Donetz. One French and three Russian steamers were also damaged, as

were shore installations and a sugar factory.

The premature bombardment had, though, ruined Souchon’s plan for

simultaneous attacks, as Goeben was

still some hours away from Sebastopol. At 4 a.m. she intercepted a Russian W/T

message, en clair, reporting the

Odessa action so that when, just before 6.30 a.m., Goeben

sighted her target, the shore batteries had been alerted and were prepared for

action. Goeben’s bombardment of

fifteen minutes’ duration did not go unanswered and she received at least

three hits from heavy shells, one of which resulted in a boiler being shut down.

This action was witnessed by Engineer Lieutenant Le Page, who had been seconded

to the Russians by Limpus. While this was going on the Russian minelayer Pruth

(loaded with 110 mines) blundered on to the scene and was promptly scuttled by

her crew who viewed their ship as being no more than a giant floating bomb

waiting to be detonated. Three modern Russian destroyers attempted to chase the

fleeing attackers but abandoned their effort when the leading boat was hit.

At the same time Hamidieh

arrived at Theodosia. With no opposition evident a German and a Turkish officer

proceeded on shore to give notice of the coming bombardment, to enable civilians

to evacuate the area. A similar warning was delivered at Novorossisk by Berk

which eventually opened fire shortly before Breslau

arrived. Breslau did not, in fact,

reach the port till 10.50 a.m., having first laid a barrage of 60 mines in the

Kertch Straits, then, with her engines stopped, she commenced a leisurely

bombardment of over 300 shells in two hours concentrating first on the oil tanks

on shore, before shifting her aim to the ships in the harbour, ultimately

sinking 14 vessels including (in contradiction to the German Official History)

the British registered steel schooner Friedericke.

All the Turco-German ships returned safely to the Bosphorus.

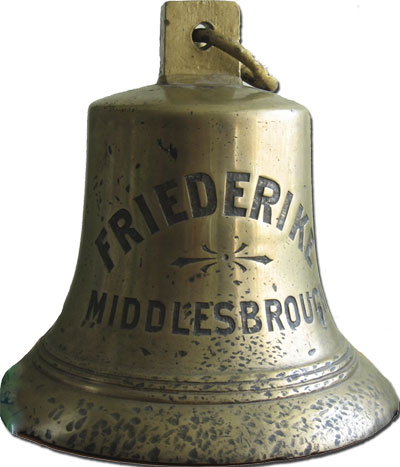

The photograph, above, of the ship's bell from Friederike

was kindly supplied by Mikhail Bobryshev (UMS-Novo Commercial Director).

The bell was found at Novorossiysk Harbour.

News of the attack, which was received in London at 5.45 that evening, 29

October,

was already common knowledge in Constantinople that afternoon. Djemal, dining at

the fashionable Cercle d’Orient, was

reported to have reacted furiously when he became aware of the news and to have

denied vehemently any knowledge of the attack; when Vere (the Armstrong-Vickers

representative) saw Djemal at 9.30 that night to ask if the rumours were true,

the Pasha – still professing to know nothing about the Black Sea incident –

lost his temper and shouted, ‘That swine Admiral von Souchon has done this.’

While Djemal’s protestations of innocence may, or may not have been, genuine

even Liman von Sanders subsequently denied any foreknowledge of the attack upon

the Russian coast.

For the personnel at the British Embassy the absence of the Turco-German fleet

from the Golden Horn did not presage the events which had now followed; even so,

an aura of calm prevailed as if, at last, a burden of uncertainty had been

lifted and everyone now knew where he stood. Ryan, for one, had left the

Embassy, as usual, at 5 p.m. while, twenty minutes later, Mallet – sanguine to

the last – telegraphed Grey that ‘Unless there are military reasons to the

contrary, I think that HM Government should continue to avoid a rupture with

Turkey.’

Precautions were, nevertheless, still taken and when Ryan returned at 6 p.m. he

‘found the Chancery being packed up, so well-prepared were we for a sudden

removal.’

Grey was, in the meantime, waiting to hear what the Russian attitude would be:

‘Unless Grand Vizier is strong enough to arrest and punish those responsible

for this outrage and make immediate reparations to Russia’, he informed

Mallet, ‘I do not see how war can be avoided, but we shall not take the first

step.’ Grey continued to be deeply concerned of the effect upon the Muslim

population of the Empire if Britain should be cast in the rôle of aggressor;

nonetheless, he could not accept Mallet’s advice.

Mallet saw Giers and Bompard that evening and they agreed between them to

suggest that, as the Ottoman Government must have had prior knowledge of, and

authorized, the attacks, the Porte should be instructed to ‘choose between

rupture with Triple Entente or dismissal of German naval and military

missions.’

Mallet should have been spared the necessity of having to make such a fatuous

demand as the following day – 30 October – Giers was instructed to ask for

his passports and Mallet, following his own instructions, proposed to do the

same; however his telegram informing Grey of his intention crossed with one from

the Foreign Secretary directing Mallet to send in a note to the Porte expressing

‘the utmost surprise of the wanton attacks made upon open and undefended towns

of a friendly country without any warning and without the slightest

provocation.’ Mallet was to demand that the Turkish Government dismiss the

German missions and repatriate the German sailors; they would have twelve hours

to produce a satisfactory reply to the note, otherwise Mallet was then to ask

for his passports.

At thirty-five minutes past midnight that night (30/31 October) a warning

telegram was sent by the Admiralty to all Mediterranean commands informing them

of the twelve hour time limit.

The countdown to war now appeared a formality. Yet Mallet, encouraged by what he

believed to be credible internal opposition on the 30th, still held out a last

lingering hope. The shock of Souchon’s fait

accompli had reverberated throughout the Porte that day in a series of

confused and emotional meetings convened by the Turks. At the first of these the

vote was 17-10 in favour of intervention upon which Said Halim, Djavid and three

other ministers promptly resigned. Enver had not, apparently, counted on Said

Halim taking so principled a stand and the Minister for War promptly went to

work: he could not afford to lose Said Halim as the Grand Vizier was a useful

figurehead who might, additionally, be able to buy time by continuing to string

along the Entente Powers. So it was that, subject to heavy pressure at the

second meeting that day, Said Halim returned to the fold — reluctant as ever

to give up the sybaritic pleasures of his post. In one sense the arguments were

irrelevant as Souchon’s action had moved the debate away from being a purely

Turkish decision: Russian soil and Russian ships had been shelled; Russian

sailors and civilians killed; and, incidentally, a British ship had been sunk.

Souchon could no longer be disavowed.

Mallet subsequently had a ‘very painful’ interview with the Grand

Vizier, who was said to have pleaded ‘Do not abandon me’. This, and

Djavid’s report of that day’s meeting, given to the French Ambassador,

resulted in Mallet informing Grey that he was ‘unwilling to leave if there is

slightest chance of change in situation during next twenty-four hours.’ The

situation, however, deteriorated rapidly: Giers left on 31 October, while

Morgenthau, the American Ambassador, advised Mallet in strict confidence to go

as soon as possible for, from the information at Morgenthau’s disposal, there

was ‘no chance of favourable solution.’ Mallet, who planned to leave that

same evening, responded to one final plea from the Grand Vizier and consented to

stay over till 1 November to allow another interview to be scheduled. This last

act of consideration for Said Halim was unnecessary: at 5.05 p.m., 31 October,

the order went out from the Admiralty to all ships, ‘Commence hostilities at

once against Turkey. Acknowledge.’

The smoke that rose from the Embassy garden told its own forlorn story: ‘the

documents and records of British achievements in Turkey for over one hundred

years were slowly burning before the eyes of the Ambassador and his Secretaries.

It was the funeral pyre of England’s vanishing power in the Ottoman Empire.’

Mallet and Ryan drove out to Said Halim’s country residence late on the

afternoon of 1 November but, as Ryan had foreseen, ‘the meeting produced no

change in an irremedial situation.’ Together with the French, Mallet and his

staff left that evening by train to Dedeagatch (the only exit as the Dardanelles

remained closed) and there boarded the SS Ernest

Simon on 2 November.

From Dedeagatch they proceeded via Athens and Malta to Marseilles, then by train

to Dieppe, finally reaching London on 11 November.

After Mallet had taken his leave on the evening of 1 November, Said Halim had

other visitors: the Grand Vizier was again wavering and Enver and Talaat arrived

to ensure his final adherence to the cause. Although now abandoned, and with war

inevitable (and Talaat reminded Said Halim that it was he who had signed the

alliance with Germany and would, therefore, be responsible for the consequences)

it apparently still took a threat to his life to persuade the Prince to comply.

As

the prevailing attitude in London regarding Turkey had already become firmly

established, this allowed the Foreign Office officials time to rehearse their

arguments to explain the unavoidable rupture of relations. The Press Bureau was,

therefore, suitably quick off the mark in issuing a lengthy statement on the

morning of 31 October in defence of Foreign Office policy:

…Ever

since the German men-of-war, the Goeben

and Breslau, took refuge in

Constantinople, the attitude of the Turkish Government towards Great Britain has

caused surprise and some uneasiness. Promises made by the Turkish Government to

send away the German Officers and crews of the Goeben

and Breslau have never been fulfilled.

It was well known that the Turkish Minister of War was decidedly pro-German in

his sympathies, but it was confidently hoped that the saner counsels of his

Colleagues, who had had experience of the friendship which Great Britain has

always shown towards the Turkish Government, would have prevailed and prevented

that Government from entering upon the very risky policy of taking a part in the

conflict on the side of Germany. Since the war, German Officers in large numbers

have invaded Constantinople, have usurped the authority of the Government and

have been able to coerce the Sultan’s Ministers into taking up a policy of

aggression…

Somewhat

embarrassingly, Sazonov hesitated over declaring war on Turkey even though the

attack upon his homeland had been flagrant and unprovoked and the Ambassador had

been withdrawn on 31 October. Such unexpected circumspection was the result of

Sazonov’s desire for Turkey to remain intact until at least 1917, when Russia

would be strong enough herself to force the issue of the Straits — his quarrel

was with Germany and Austria-Hungary. Rather like the Grand Vizier, Sazonov

seemed to believe that, by ignoring the problem, it might go away; only a direct

order from the Tsar secured the Russian declaration of war against Turkey on 2

November. This unanticipated Russian intransigence resulted in Britain

involuntarily leading the way to strike back at the Turks.

At the Cabinet on 2 November Grey reported that the situation in Turkey

was still obscure; despite this, the general opinion was that, after what had

happened, there should be a vigorous offensive and every effort should be made

to bring in Greece, Bulgaria and, above all, Roumania. ‘Henceforward’,

Asquith reported to the King, ‘Great Britain must finally abandon the formula

of “Ottoman integrity” whether in Europe or in Asia.’

While the politicians debated, far away, off the Dardanelles, the last futile

act of the drama was being played out. On the back of the Admiralty copy of

Grey’s telegram to Mallet of 30 October, which set the Turks a twelve hour

time limit to respond to the British ultimatum, Churchill had written in blunt

red pencil, ‘1 S[ea] L[ord]. Admiral Slade shd be asked to state his opinion

on the possibility & advisability of a bombardment of the sea face forts of

the Dardanelles. It is a good thing to give a prompt blow.’

Slade replied the same day:

A

bombardment of the sea face of the Dardanelles Forts offers very little prospect

of obtaining any effect commensurate with the risk to the ships. The Forts are

difficult to locate from the sea at anything like the range at which they will

have to be engaged. The guns in the Forts at the entrance are old Krupp and

would probably be outranged by those in the Fleet, but it is not known where the

new guns 16.5" Krupp said to have been mounted by the Germans are situated.

It may be possible to make a demonstration to draw the fire of these guns &

make them disclose themselves trusting to lack of training of the gunners —

but it would not be advisable to risk serious damage to any of the battle

cruisers as long as the Goeben is

effective — A little target practice from 15 to 12 thousand yards might be

useful....

The

following day, 1 November, the order was sent to Admiral Carden: without risking

either his own or the French ships a demonstration was to be made against the

forts on the earliest suitable day from long range and with the ships underway.

Approaching soon after daylight, Carden was instructed to retire before return

fire from the forts became effective; and, lest Carden should entertain any

doubts that this was just another of Winston’s caprices, Churchill ended the

signal by declaring that the First Sea Lord concurred.

This reassurance might not have been as comforting as Carden imagined.

Battenberg, at the end of his tether after constant attacks in the press

questioning his patriotism, was unwell and no longer up to the job. The

whispering campaign had been so effective that, as early as 30 September,

Commander Domvile recorded in his diary that ‘There is a persistent rumour

that P[rince] L[ouis] is shut up in the Tower...’

Churchill’s own performance was also coming under increasing criticism after a

series of failures

and, to protect his own position, a change was required at the Admiralty — a

First Sea Lord with energy and ideas. It was, apparently, Haldane who first

suggested, on 19 October, that Fisher should return to the Admiralty (in

addition to Admiral Sir Arthur Wilson).

Churchill received Asquith’s approval for the change the following day; the

Prime Minister had not found in Prince Louis a congenial colleague when

Churchill’s absences had forced them to work together. ‘I think’, Asquith

informed Venetia Stanley that afternoon, ‘Battenberg will have to make as

graceful a bow as he can to the British public.’

The changeover was not all plain sailing however as the King, who was, on the

one hand ‘a good deal agitated’ about Battenberg’s position, was equally

horrified at the prospect of Fisher’s return. The pretext Churchill required

was provided on 27 October when the new super-dreadnought Audacious

struck a mine and was lost.

The First Lord saw Asquith that morning to report the catastrophe and was

described by the Prime Minister as being ‘in a rather sombre mood’ — a

considerable understatement. ‘Strictly between you & me’, Asquith

confided to Miss Stanley, ‘he has suffered to-day a terrible calamity on the

sea, which I dare not describe, lest

by chance my letter should go wrong…He has quite made up his mind that the

time has come for a drastic change in his Board; our poor blue-eyed German will

have to go, and (as W. says) he will be reinforced by 2 “well-plucked

chickens” of 74 & 72…’

By the 28th Asquith was adamant that Battenberg must go; Churchill had had a difficult interview with the Admiral

made all the more poignant as Prince Louis’ nephew had been killed in action

the previous day. Now thoroughly dispirited, ‘Louis behaved with great dignity

& public spirit, & will resign at once.’ Still, though, the King had

an ‘unconquerable aversion’ to Fisher. Asquith played his part in the coup

to the hilt, declaring to the King’s private secretary that nothing would

induce him to part with Winston, ‘whom I eulogised to the skies, and that in

consequence the person chosen must be congenial to him.’

Battenberg resigned, a broken man. It was, the Prime Minister admitted, a much

more difficult job to get the King to consent to Fisher’s appointment than it

was to get his approval of Battenberg’s resignation. At an interview with the

King, after lunch on 29 October, Asquith wrote that

He

gave me an exhaustive & really eloquent catalogue of the old man’s crimes

& defects, and thought that this appointment would be very badly received by

the bulk of the Navy, & that he would be almost certain to get on badly with

Winston. On the last point, I have some misgivings of my own, but Winston

won’t have anybody else, and there is no one among the available Admirals in

whom I have sufficient confidence to force him upon him. So I stuck to my guns,

and the King (who behaved very nicely) gave a reluctant consent. I hope his

apprehensions won’t turn out to be well founded.

The

old reprobate was back at the Admiralty on 30 October, the day Churchill had

determined that Carden should bombard the Dardanelles’ forts. By this time

Churchill had already – in as much as it was possible for him – developed a

grudge against Turkey; but it is also tempting to suggest that the precipitate

order to Carden owed more than a little to Churchill’s desire to impress

Fisher and to demonstrate to his critics that the Admiralty was now under new

management, with past disasters forgotten, and resolute action to come. However

difficult it might be to untangle the swirling mix of motive and emotion wrapped

up in the order to Carden, it is without question that it was to have the most

damaging consequences.

The infallible Captain Richmond was, as usual, less than impressed with

the Admiralty’s way of conducting business; it was an infelicitous attribute

of Richmond that he always believed he could do the job better himself. ‘Of

course’, he recorded on the day the order was sent, ‘Sturdee has no notions

of what to do [about Turkey] beyond the crude one of sending a ship to fire upon

their troops between Gaza & El Arish, & even that I had to suggest to

him…It is pitiful to see the lack of co-operation between Army & Navy in

this matter…’

Limpus, now ensconced at Malta, also became aware of the order to Carden and was

so concerned he sent Sturdee a personal telegram on 2 November urging caution:

My

knowledge of Turks leads me to think result would be reported widespread in

Constantinople Allied Fleet have attacked and have been repulsed with serious

loss. Naturally have no knowledge of plan, but it seems to me that first thing

to free passage of Straits is a land attack on forts on Asia side.

As

far as Richmond was concerned, this looked like the end of the matter. He noted

on 3 November that orders had been sent to bombard the forts, ‘but Limpus

pointed out that such an action could not be conclusive & the Turks would

use our necessary withdrawal to boast of a victory. So I dare say we shall not

do it...’

For once, Richmond was wrong. At 5.45 that morning Carden’s ships had opened

fire, his objective being ‘to do as much damage as possible in a short time

with a limited number of rounds at long range, and to turn away before the fire

from the forts became effective.’ To accomplish this, he allowed a mere eight

rounds per turret.

Britain had commenced hostilities before

the official declaration of war!

The immediate results were better than expected, particularly those

obtained by the British battle cruisers, and included the destruction of Fort

Seddel Bahr when its magazine exploded after being hit. ‘It seemed to me’,

noted an onlooker on Dublin, ‘to be

a deliberate bombardment of practically every building in sight, care being

taken not to hit the minaret. This would be because of its use for range finding

and also perhaps of a wish not to offend religious sensibilities. The main

target was certainly the fort, which we made a mess of, culminating in a huge

explosion. There had been sporadic return fire from several positions but we

certainly weren’t hit and it was all a most one-sided affair.’

Djevad Pasha, the Turkish commandant, testified after the war that this attack,

though more or less a reconnaissance, caused more damage than any succeeding

attack.

‘The Turkish guns were quite outranged’, noted the commander of HMS Harpy,

‘and as far as I could see, only a few ricochets came near us…I hope this

war will be prosecuted with vigour, and that we shall not be content with a 20

minute bombardment occasionally.’

Asquith, however, was less impressed: ‘The shelling of a fort at the

Dardanelles seems to have succeeded in blowing up a magazine’, he wrote,

adding cynically, ‘but that is peu de chose. At any rate we are now frankly at war with

Turkey…’

This was, in a formal sense, still incorrect.

In Constantinople von Usedom admitted that the long range shooting had

been remarkably good and the demonstration had produced near panic in the

capital, resulting in a conference being convened of Government representatives

and town authorities to discuss the measures to be taken to safeguard the city,

its treasures, valuables, holy places, and the Sultan. There was even talk of

laying a minefield in front of the Golden Horn

while steam was raised in Goeben so

that she could sail to the Dardanelles and assist if necessary.

In London the Cabinet reached the conclusion that, due to the bombardment and

destruction of the fort, ‘a final declaration of war against Turkey could no

longer be postponed.’

On the afternoon of 4 November Tewfik Pasha, acting under instructions from

Constantinople, called on Grey and asked for his passports. The following day

Britain and France declared war on Turkey. Churchill would not let up; he asked

Carden four days later to report on any way the Turks could be injured

‘without undue risk or expenditure of ammunition.’

Carden was not keen, replying that there was not much that could be done at

present without using a full charge in the 12-inch guns.

Undeterred, Churchill again asked Carden for his proposals for injuring the

enemy.

Almost in desperation, Carden replied that, apart from preventing contraband

entering through the Dardanelles or Smyrna, which he was already doing, the only

other option was a further bombardment.

‘The bombardment should be repeated’, Churchill instructed on 16 November

before Vice-Admiral Oliver’s timely intervention prevented another futile

demonstration. ‘Possibly’, the Admiral minuted, ‘the guns have not enough

remaining life to make it advisable to bombard again with full charges.’

The proposal lapsed — for the time being.

Carden’s few rounds had blown up a fort; this short term damage, and

the temporary panic in Constantinople (which soon subsided), were however in no

way offset by the long term consequences of Churchill’s folly. As a result of

the First Lord’s ‘prompt blow’ the following improvements were made to the

defences of the Dardanelles:

i.

damage done to Seddel Bahr repaired

ii. number of 15 cm L/40 QF guns at Dardanos increased from 2 to 5

iii. a new battery, 3 x 15 cm L/40 QF naval guns, had been completed at

Messudieh on European shore

iv. the minefield batteries had been greatly strengthened by addition of a

number of fixed light QF guns removed from Turkish warships and by several mobile field batteries

v. additional minefields had been laid

vi.

searchlights had been increased in number and power

vii. between

50 and 60 mobile mortars and howitzers had been established in concealed

positions on both

sides of the Straits, between the inner and outer defences

viii.

the range-finding, fire observation and control systems had been improved

ix.

the emplacement of the heavy gun batteries had been strengthened by

increasing the thickness of earth covering of traverses and parapets, and

the provision of sandbag buttresses and revetments to protect gun

crews and ammunition stores

x. the construction of Djevad Pasha battery (3 x 15 cm L/26 Krupp

guns) had been commenced near White

Cliffs and was approaching completion at end of February 1915.

This

report made for depressing reading but contrasted markedly with Churchill’s

own evidence at the Dardanelles Commission: ‘…as far as I can recollect’,

he answered at that time,

the

object was to see what the effect of the ships guns would be on the outer forts

— whether they would injure them…It lasted only 10 minutes. We thought it

would be useful to ascertain this, and also, the war having just begun and the

Fleet having waited off the Dardanelles for some weeks, it seemed a convenient

moment to exchange shots with the forts and to acquire any information about the

effect of the guns on the forts…It did not seem likely to do any harm in the

way of putting the enemy specially on their guard, and in fact it did not

produce any evil consequences; the enemy took no steps in consequence of

it...’

Despite

Churchill’s prevarication, the Report of the Dardanelles Commission concluded

that the demonstration, which was characterized as “unfortunate”, was ‘a

mistake, as it was calculated to place the Turks on the alert’ and it was made

clear that the orders to bombard had emanated solely from the Admiralty — the

War Council had not been consulted.’

Although, clearly, the Dardanelles defences were being strengthened

before the bombardment the main purpose of this was to prevent the ingress of

the Allied fleet and so give the Turco-German fleet a free hand in the Black

Sea. Neither the troops nor equipment were then in place to have repelled a

combined operation. Just as important, the emphasis of the Turco-German defences

was altered: mines would now be adopted as the primary weapon, and the guns on

both shores would be deployed to protect the minefields. It was this decision

which would eventually seal the fate of the Dardanelles Expedition.

Churchill was obviously concerned enough about the advance warning he had

provided of a possible allied attack for him to want to deny, in his evidence,

the fact that this affected Turkish planning.

Lloyd George certainly ‘partly blamed’ Churchill for the war with Turkey:

‘The situation was not desperate even after the attacks by the Goeben

on Russian Black Sea Ports’, the Chancellor maintained in Scott’s record of

the conversation. The Turks ‘did not concern us and it was open to Russia to

ignore them but the perfectly useless bombardment by the fleet of one of the

Dardanelles Forts and the seizure of Akaba brought us at once into war.’

Churchill had, in effect, launched his own private war against Turkey.

Feroz

Yasamee has argued that the three factors which ‘tipped the balance in favour

of intervention’ were: ‘the German alliance, which Talat in particular was

reluctant to betray; the presence of the Goeben

and Breslau, which gave the Empire naval security against Russia, as

well as an easy route into the war; and the Germans’ offer to subsidize the

Ottoman war effort.’

Of the three, only the possession of the German ships, under German command,

could guarantee Turkey’s entry into

the war. It was feasible that, without the presence of the German ships, Turkey

could, if so inclined, have kept out of the war indefinitely. Despite the fact

of the Turco-German alliance on 2 August, little had happened since: on the day

after the signing a British Admiral still remained in charge of the Turkish

fleet and would continue to do so for another month. Despite a report to the

contrary from the Military Attaché, the Turkish mobilization was lethargic, a

result in part of dire economic necessity. By September, German hopes that

Turkey would participate actively in the war rested with Enver Pasha, the

Minister for War, whose position was not strong enough to allow him to take

unilateral action. Enver’s first attempt to force the issue – his

authorization to Souchon on 14 September to patrol in the Black Sea in an

endeavour to manufacture an incident – soon fell foul of the

anti-interventionists in the Turkish Cabinet. This rebuff was viewed so

alarmingly by the Germans that von Usedom admitted that the various German

technical missions existed ‘only through Enver, and depend on him for

results’. Von Usedom further believed that if the anti-interventionists gained

the upper hand ‘the prospect of working

with the Turks will have passed.’

When dealing with these arguments, the wider strategic position should

not be overlooked; indeed it would come to assume crucial importance. During

August it appeared as if the German forces would soon achieve the victory that

was widely expected. Not until early September was the German advance on the

Western Front checked after which there would be an impending stalemate.

Similarly, despite an initial crushing victory in the East, Austro-German forces

had received a check at the First Battle of Warsaw while, further south, the

Austrians were being hard pressed by the Serbs. By October, it was no longer

possible to assume automatically that the only result of the war would be a

German victory. Yet it was the chance to regain territory as a result of a

victorious march with the Central Powers that weighed so heavily in the counsels

at the Porte. Once the issue was in doubt, if only slightly, Enver lost a key

bargaining point. Worse, if it appeared that the Entente Powers might actually

be making some headway, the arguments in favour of continuing Turkish neutrality

would be overwhelming. Enver had little choice but to force the issue before

news was received of a setback to German arms.

To accomplish this task his method of attack was two-pronged: a demand

for German gold which, when forthcoming, at least invoked a moral debt for

Turkey to enter the lists and second, if all else failed, a direct order to

Souchon to attack Russian ships. The Turkish demand for T£2 million was quickly

met by the Germans; however, this was not as conclusive as it might have seemed,

as previous shipments had been sent to little effect. Mallet had already

surmised that the Turks might be playing with the Germans, ‘and having

obtained from them soldiers, sailors, cannons, supplies, money and promises they

are now showing great and increased reluctance to pay the bill.’

Similarly, when on 23 October Mallet became aware of the latest shipment of

gold, he maintained that this ‘need not indicate immediate declaration of

war’.

A further complication had arisen for Enver following the death of King Carol of

Roumania which cast some doubt on the prospect of Roumania aligning herself with

the Central Powers; indeed, the very possibility that she might gravitate

towards the Entente, when combined with the lack of German progress on the

battlefield and the weak position of the Turkish forces, was enough to warrant

talk of a Turkish envoy being sent to Berlin to plead for a further six months

of neutrality.

The only sure means by which Enver could force his country into the war

rested solely with the command of Admiral Souchon. Before it was too late, on 25

October 1914, Enver issued the fateful orders to Souchon.

Two things should be noted in Enver’s orders: first, that Souchon was directed

to attack the Russian fleet and

second, that the Turkish fleet was to

gain mastery of the Black Sea. Clearly however, the second task would have been

beyond the means of the Turkish fleet without the presence of Goeben

and Breslau, while Souchon himself

decided to go a step further and attack the Russian mainland. Between them,

Enver and Souchon ensured Turkey’s entry into the war at the end of October

1914. The question remains, could Enver have achieved the same result without

the presence of Souchon’s squadron?

Captain Reginald Hall, the Director of the Intelligence Department at the

Admiralty from October 1914, maintained in evidence before the Dardanelles

Commission that, ‘From very certain information one could definitely say that

the entry of Turkey into the war was forced by the guns of Goeben, by Goeben actually

arriving there – that the entry of Turkey was by no means a unanimous opinion

of the Young Turk party itself.’ When queried on this point, Hall reiterated,

‘Yes, there is unquestionable evidence that their arrival there forced Turkey

into the war.’

Lloyd George also maintained that the escape of Goeben

and Breslau ‘was directly

responsible for the entry of Turkey into the War.’

Despite their insistence, the question of whether it can be established beyond

doubt that the acquisition of the German ships caused Turkey’s entry into the

war is fraught with imponderables: for how long could the Ottoman Government

have resisted the unrelenting German pressure? What was the possibility of a

Russian incursion on Turkey’s eastern frontier which would have resulted in

war from another direction? Would the simmering dispute with Greece over the

Aegean Islands have dragged the Turks into a wider Balkan conflict? Nevertheless

possession of the two ships greatly facilitated the onset of war by ceding to

Turkey at a stroke command of the Black Sea; furthermore Admiral Souchon had a

degree of latitude available to him in his actions that did not fall to General

Liman von Sanders, the head of the German Military Mission to Turkey. The

Turkish game of avoiding action for as long as possible was transparent and

Souchon certainly hastened its conclusion; as he himself declared, ‘I have

thrown the Turks into the powder-keg and kindled war between Russia and

Turkey.’

It is difficult to see what options would have been available to Enver if

Souchon had not successfully escaped the clutches of Admiral Milne. With

recollections still fresh of its poor showing against the Greek Navy in the

Balkan Wars, the Turkish fleet, as it stood before Goeben’s

arrival, could not have hoped to sortie into the Black Sea with any certain

prospect of a successful encounter with the Russian Black Sea Fleet. With this

path closed Enver would presumably have pushed for a Turkish advance upon the

Suez Canal, yet with this option he faced the resolute objection of General

Liman von Sanders who strongly doubted the value of this operation. Enver

himself admitted that a sizeable proportion of the Ottoman Army would still have

to be committed to a defensive posture in Thrace. It is reasonable to presume

that Enver might have been placed in the position of having to rely upon a

Russian incursion through Persia as a pretext but, with her hands full

elsewhere, would the Russians have been so foolhardy? Otherwise he could have

tried to force the Russians’ hands by closing the Dardanelles. Yet, when first

approached by von Usedom early in September 1914 with a request to close the

Straits and complete the mine barrier, Enver at first demurred as the result

might be an Entente ultimatum which could lead to a war that the Turks were then

anxious to avoid until assured of Bulgaria and Roumanian non-intervention.

However, when, within a month, a new minefield had been laid and the Straits

closed there was no ultimatum. Whether the Russians would have continued to

accept this state of affairs if war against Turkey had not broken out in

November is problematical; however, as pointed out above, they were hard pressed

in the north and could ill afford the opening of a new front.

If Enver could not have forced the issue in the way he did, and Turkey

thereby remained neutral, within a month the news from all fronts would have

been less than reassuring and certainly would have emphasized the fact that

there was little expectation of a quick German victory.

Would much have changed if Turkey had maintained her shaky neutrality into 1915?

It is difficult to imagine that the agonizing of the British Cabinet over the

stalemate on the Western Front in December 1914 would not still have taken

place. New troops were becoming available, including the Empire contingents, and

there would still have been anxious debate in London before they were

dispatched, as Churchill complained, to chew barbed wire in Flanders. In that

case, presumably, Lloyd George’s suggestion of an attack upon Austria would

have been canvassed more thoroughly.

Further, if the Dardanelles remained closed even though Turkey continued her

neutrality (and this was always a distinct possibility), there would have been

heavy pressure applied by the Entente Powers to force a re-opening. At any time

an ‘incident’ might have occurred off the Straits. All these suppositions

were rendered irrelevant by Souchon’s actions in the Black Sea on 29 October

1914. Germany had supplied the means and on that morning Souchon achieved the

end. Souchon’s disregard for Enver’s orders revealed fully who was in

control at the Porte. As Admiral Limpus noted in his last letter from

Constantinople, ‘Patience, and events unfavourable to Germany, coupled with

resentment against German presumption, may yet cause the Turks to discuss with

Great Britain, or France, the means of ridding themselves of their present

masters.’ Limpus believed that ‘even without menaces, patience and the logic

of events will make it difficult for the Germans to persuade the Turks to make

an irretrievable false step.’

Where persuasion failed, Souchon acted. Without Goeben

how different it might have been.

|