|

Grey immediately lodged an official complaint at the Porte, instructing Beaumont

to point out that the Turkish Government must not allow acts of war to be

perpetrated in the Straits by the German ships.

Souchon himself, meanwhile, was on his way to Constantinople having been picked

up by the Hamburg-Amerika line steamer Corcovado,

which had been armed as an auxiliary cruiser and, while at Constantinople, had

taken on board the crew of the German stationnaire Loreley;

it was the arrival of Corcovado that

Wangenheim had waited nervously for that morning in the presence of Ambassador

Morgenthau.

Souchon’s other auxiliary – General,

of the German-East Africa Line (complete with captive American doctor)

– had arrived at the Straits during the night of 10/11 August, after acting as

a W/T relay vessel during the final stage of the escape.

Souchon, who began a round of talks with Wangenheim, Liman and Enver,

quickly came to the conclusion that operations should begin in the Black Sea as

soon as possible (Goeben needed 8,000

new boiler tubes and 50 boiler makers to fit them)

and that German engineers should take the responsibility for strengthening the

fortifications of the Straits. The British declaration of war against Austria on

the 12th had ended, finally, any thought of a dash to the Adriatic, a fact which

was acknowledged by the Admiralty Staff who instead approved Souchon’s Black

Sea proposal ‘with the concurrence of Turkey or against her will.’ Although

Souchon was to act in concert with Wangenheim, the Admiral was left with the

discretion to commence operations if he thought that, by so doing, it would

hasten the lethargic Turkish mobilization.

Wangenheim, who had already had to cope with the frustrated Liman, now had

another senior officer on his hands anxious to come to blows with the Russians.

The arrival of the German ships sat oddly alongside Enver’s weekend

offer of a Russo-Turkish alliance and, as Giers was quick to point out, the

situation had not altered to Russia’s benefit: the self-esteem of the Turks

had been considerably strengthened by the arrival of Goeben

and Breslau and, the Ambassador

believed, ‘may inspire them with temerity for the most extreme steps.’ Giers

would follow Sazonov’s orders to vacillate with some reluctance as it was his

opinion ‘that a decision should be taken without delay if we contemplate the

possibility of joint action with Turkey, as even tomorrow it may perhaps be too

late.’

When the Ambassador saw the Grand Vizier on the morning of Thursday 13th to

press for the removal of the German crews he was, unlike Beaumont, given

‘assurances of a fairly satisfactory nature’

which, however, were not sufficient enough to remove the fears in St Petersburg

‘that Turkey intends to use Goeben

for hostilities in the Black Sea.’

Prompted by these fears, Sazonov suddenly moved with alacrity.

In speaking to the French and Russian Ambassadors on 15 August, Grey had

pointed out how desirable it was ‘not to fasten any quarrel upon Turkey during

the present war…It would become very embarrassing for us, both in India and in

Egypt, if Turkey came out against us. If she did decide to side with Germany, of

course there was no help for it; but we ought not to precipitate this. If the

first great battle, which was approaching in Belgium, did not go well for the

Germans, it ought not to be difficult to keep Turkey neutral…’

Indeed, the somewhat muted response by Britain to the presence of Goeben

and Breslau had thrown a spanner into

the German works. Unable, for the present, to use the ships to force Turkey into

the war, German ambitions now focused on the attainment of another goal, the

declaration of jihad — holy war.

However, rather than follow Grey’s circumspect and eminently pragmatic lead,

Sazonov proposed to buy Turkish neutrality with the promise of a guarantee of

her territorial integrity; plus all the German concessions in Asia Minor; and

the abolition of the Capitulations.

Having acted at last, Sazonov, characteristically, now wanted to go too far;

caught up in the maelstrom he had helped to precipitate, the artless Foreign

Minister did not know which way to turn. Grey was not impressed: ‘Turkey’s

decision’, he told Benckendorff, ‘will not be influenced by the value of the

offers made to her, but by her opinion which side will probably win and which is

in a position to make the offers good.’ In Paris Bertie, as ever, was more

cynical and more inclined to trust to the natural inertia which infected Turkish

political action, for he had heard that ‘at a recent Cabinet council at

Constantinople Enver Pasha wished war to be declared against Russia, and he

produced a revolver to support his wish, but all his colleagues did ditto, and

war was not declared.’

The calculated passivity of the Foreign Office was not matched by the

Admiralty. Milne had been signalled on the 12th that, with the German cruisers

‘being disposed of’ and Austria the only remaining enemy in the region, the

armoured cruisers (with the exception of Defence)

would be withdrawn from the Mediterranean. Milne himself was directed to return

in his flagship, Inflexible, while the

other two battle cruisers maintained a watch on the Dardanelles.

By Saturday 15 August however, as the Turks continued to show little inclination

to repatriate the German crews and ever mindful therefore that the ships might

re-emerge, Battenberg considered the ‘situation as regards Goeben

and Breslau is so unsatisfactory’

that new dispositions were required: all the destroyers and Defence were to proceed at once to the Dardanelles and establish a

‘close watch for enemy ships.’

Churchill, trying to retrieve a situation that had gone badly wrong following

Souchon’s escape, also decided to weigh in with his own personal initiative.

‘Don’t jump’, he implored Grey on the 15th, ‘but do you mind my sending

this personal message to Enver. I have answered this man & am sure it will

do good. But of course your ‘no’

is final.’ The First Lord of the Admiralty enclosed the letter he intended to

send to the Turkish Minister of War:

I hope you are not going to make a mistake which will undo all the

services you have rendered Turkey & cast away the successes of the second

Balkan War. By a strict & honest neutrality these can be kept secure. But

siding with Germany openly or secretly now must mean the greatest disaster to

you, your comrades & your country. The overwhelming superiority at sea

possessed by the navies of England, France, Russia & Japan over those of

Austria & Germany renders it easy for the 4 allies to transport troops in

almost unlimited numbers from any quarter of the globe & if they were forced

into a quarrel by Turkey their blow could be delivered at the heart.

On the other hand I know that Sir Edward Grey who has already been

approached as to possible terms of peace if Germany & Austria are beaten,

has stated that if Turkey remains loyal to her neutrality, a solemn agreement to

respect the integrity of the Turkish Empire must be a condition of any terms of

peace that affect the near East.

The personal regard I have for you, Talaat & Djavid and the

admiration with which I have followed your career from our first meeting at

Wurzburg alone leads me to speak these words of friendship before it is too

late.

Churchill

suggested to Grey’s private secretary that, once ciphered and sent to

Constantinople, the appeal should be entrusted to Admiral Limpus to give to

Enver ‘thus making it a personal message from me & different from the

regular diplomatic communications.’

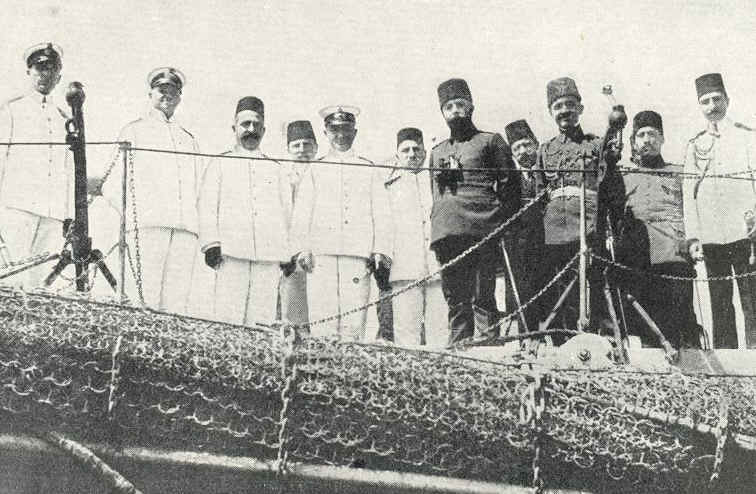

Djemal Pasha (with field glasses) on board SMS Goeben

Limpus had problems of his own however; his position at the Porte had

become increasingly unclear. On 14 August Beaumont reported that Djemal, seeking

to defuse the issue of the German ships – which the Turks had now renamed Yavuz

Sultan Selim and Midilli

– ‘promised Admiral Limpus to hand over two German ships bodily to him. He

will make crews for them. It will be slow, but it will be done.’

In making this offer Djemal was obviously counting on his ostensible pro-Entente

credentials outweighing the suspicion that should have been engendered in the

minds of Beaumont and Limpus. Yet already, four days before Djemal’s promise,

the British Commodore of the Turkish flotilla, Lieutenant Boothby, had been

transferred to shore work on the feeble excuse that, having not been long in

Constantinople, he ‘could not know his Turkish officers.’

Nevertheless Beaumont was prepared to accept that there was no intention of

sending the German ships outside the Sea of Marmora until the conclusion of the

war and that, while the formalities of the transfer would ‘technically be

complete in a day or two’, further delays before taking delivery were

inevitable; it was, he informed Grey, the opinion of Limpus ‘that it will

probably be nearer a month before Turkish crew can even move Sultan

Selim.’

Limpus’ real problems began when he naïvely sent a letter to Djemal,

enclosing a report to be submitted to the Grand Vizier.

The Minister of Marine naturally read the report, in which Limpus advocated

strict neutrality in view of the condition of both the fleet and the army.

Limpus also ventured the opinion – according to Djemal – that Turkish

officers would need four to five years’ training before they were capable of

handling Goeben and Breslau.

Djemal replied at once:

I

have perused the takrir containing

certain observations touching the foreign affairs and policy of the Imperial

Government, given to be presented by my intermediary to the Grand Vizier. The

writing and presentation of this takrir

of yours merits criticism from two points of view. (1) Your Excellency is Naval

Adviser and consequently under the Ministry of Marine. Therefore, in your

reports and takrirs, no matter to what

they may relate, you can only address the Minister of Marine. (2) Although your takrirs

should only relate to the re-organization of naval affairs, this takrir

of yours contains diplomatic observations relating to the foreign policy which

the Naval force of the State would render necessary, a question wholly outside

your competency and power. While begging that attention may be given to these

important particulars, I confirm my good will…

Djemal

later maintained that Limpus replied by letter the following day (Saturday 15

August) that, while he would not exceed the imposition placed on his activities

by Djemal, in any event he was feeling very tired and wished to spend more time

with his daughter at Therapia.

The reality was very different — Limpus was called to the Admiralty

building that morning by wireless and, at the behest of Souchon, was summarily

replaced by a Turkish Frégate Captain.

This was a bitter disappointment to Beaumont on his last day in charge, for

Ambassador Mallet was due to return on the 16th. The Chargé d’Affaires

telegraphed Grey at midday on the 15th:

Admiral

Limpus and all officers of his mission have been suddenly withdrawn from fleet,

replaced in their executive command by Turkish officers, and ordered, if they

remain, to continue work at Ministry of Marine. I am at a loss to understand

significance of this movement. Although I have been given to understand by a

member of the Government that they are still anxious to get officers and crew of

Goeben and Breslau out of the country it will probably mean retention at least

of mechanics and technical experts which will create most dangerous situation in

the face of attitude likely to be taken by Russia. There is very prevalent

anxiety as to Russia’s intentions which could only be allayed by positive

assurance from France and Great Britain that they will guarantee integrity of

Turkey. Minister of Finance [Djavid] asked me point blank this afternoon if we

were prepared to do this. Definite pronouncement of this nature would do much to

clear the situation and would have best effect unless Turkey had already been

too deeply compromised by mischievous intrigues.

For

Eyre Crowe, the removal of the Naval Mission was the last straw: ‘The Turks

are, and have been, playing with us’, he minuted. ‘I do not believe that any

declaration on our part will have any effect.’

Crowe went further in a memorandum he addressed to Grey on Sunday 16th in which

he was concerned that, if war broke out, Limpus and the other members of the

British Naval Mission would be interned. Before allowing this to happen, they

should be recalled at once, using the pretext that the removal of Limpus from

his command by Djemal represented a breach of contract. Crowe admitted that

their places would be taken by Germans, but saw this as inevitable anyway;

besides, if the Mission could be got away before the Turks had a chance to

detain it, this would give ‘a clear battle cry in regard to public opinion in

India or Moslem feeling in any part of the world.’ In addition, Crowe urged

that Greek naval co-operation should be obtained to assist in watching the

Dardanelles, which would also provide the incidental benefit of being able to

use Greek islands and harbours as naval bases; and, most provocatively, he

suggested that the Russians be asked ‘that they would do well, if they could,

to mine the northern exit from the Bosporus...’

Although Grey was reluctant to consider this last measure, which might result in

the destruction of British merchant vessels, as a precaution (just in case the

Russians should have independently arrived at the same conclusion) Beaumont was

instructed that all British vessels ‘should be warned to leave Turkish waters

at once.’

The news from Constantinople continued to be depressing. The

representative there of Armstrong’s, Captain Vere, was informed that he was to

be sued by the Turkish Government for £15 million for non-delivery of the

embargoed ships, with the further threat that the claim might be submitted to

the Hague Tribunal! Vere was naturally anxious that a statement should be made

that the ships would be returned to Turkey if not required during the war which,

he thought optimistically, combined with the suggested declaration of Ottoman

integrity, ‘would finally detach Turkey from the side of Germany and

Austria.’

When Beaumont chimed in that, for the moment, an indulgent attitude would be the

best policy and that ‘Feeling against England for having taken the ships is

very strong and some allowance must be made for it’ Churchill, like Crowe, had

had enough. Sensitive to the charge that he had acted precipitately, with the

red ink reserved for the use of the First Lord, Churchill minuted Beaumont’s

dispatch, ‘This will not do. A strong protest must be made to F.O. 2

Battle cruisers are detained while this uncertainty continues.’

Despite the pressure he was subject to by the Admiralty and his own officials,

there was little Grey could do except follow the course he had already outlined

of not fastening upon any quarrel with Turkey. In this, he had one important

ally in Kitchener who, fearing an attack upon Suez, was ‘insistent’ that

Turkey be kept neutral as long as possible. ‘The objective before us was

therefore twofold,’ Grey subsequently admitted: ‘(1) to delay the entry of

Turkey into the war as long as we could, and at all costs till the Indian troops

were safely through the Canal on their way to France; and (2) to make it clear,

if the worst had to come, that it come by the unprovoked aggression of

Turkey.’

After

Souchon had been instrumental in having Limpus removed, it was agreed that the

two German ships would weigh anchor and proceed to Constantinople where, at

Principo Island, Turkish officers would temporarily relieve their German

counterparts before the warships steamed the short distance to the Golden Horn,

there to be paraded publicly as Turkish ships. On the morning of the 16th the

French steamer Ionic reported that she

had witnessed Goeben and Breslau hauling down the German colours to hoist the Turkish before

steaming away slowly in the direction of Ismid

though with Souchon’s own ensign still fluttering — a personal reminder to

the Turks as to who was really in charge. The sight of the German crews lining

the deck, and of Souchon’s ensign, was too much for Captain Raouf Bey who had

now returned from Newcastle having lost the command of one fine ship and who,

having been promised the command of one of the German ships, saw himself being

deprived a second time. Just as eager as the British to see the repatriation of

the German crew, when his complaint to Djemal was shrugged off, Raouf then asked

to be made commander of the torpedo flotilla ‘so we can surround these ships

and force the crew out.’

Raouf’s transparent patriotism was a liability for Djemal. The Minister of

Marine had an ulterior motive in wanting Souchon in charge of the Ottoman fleet

and the unfortunate Raouf was soon after dispatched to Afghanistan on a

“diplomatic mission” — a characteristic act by Djemal but a poor reward

for the Captain’s conspicuous services. Thereafter, the German ships would be

a familiar sight, lying at anchor, their masts and funnels masked by the jumble

of minarets tumbling down to the shore.

As the grand ceremony was taking place in the Golden Horn Beaumont was

again receiving the ‘most solemn assurances’ from the Grand Vizier of

Turkish neutrality; desperate for anything to corroborate this, Beaumont

reported ‘Good sign is that ships have now been transferred and are now flying

Ottoman flag under nominal command of Turkish officer.’ The Chargé also

credulously accepted the reasoning that some of the German crew would have to

remain on board and that a ‘mixed crew of Germans and Turks under direct

orders of Admiral Limpus would have been impossible combination and perhaps

sufficient explanation for withdrawing him from executive command.’

Meanwhile, off the Dardanelles, Captain Kennedy aboard the battle cruiser Indomitable

was collecting Mallet from an Italian mail steamer which had ferried the

Ambassador on the last leg of his journey from London, via the Legation in

Athens where Mallet had been brought up to date on events including the

‘sale’ of Goeben and Breslau.

With the handing over ceremonies completed Souchon went ashore for a

meeting that evening with his compatriots Liman, Kress and Bronzart — but with

only Enver and his second in command, Hafiz Hakki, representing the Turks.

Inevitably, Enver was pressed to speed up the mobilization before attention was

turned to the various strategic alternatives available to the Turco-German

forces. Liman’s suggested option was for a landing of Turkish troops on the

Black Sea coast between Odessa and Ackermann, to divert Russian troops and so

relieve some of the pressure on the southern wing of the Austro-Hungarian front.

Black Sea operations were, however, deemed to be politically inexpedient as they

might incite the British to try to force the Dardanelles, whose defences at the

time were ‘seriously deficient’.

The preferred scheme (which also had Souchon’s backing) was for an attack on

Suez for the dual purpose of restoring Turkish sovereignty and cutting off

British reinforcements en route to the Western Front.

Liman, with some justification, could not understand how it was proposed that

Turkey, with her limited resources and poor communications, could hope to

conquer Egypt and his reluctant acceptance that this was indeed the intention

only added to the General’s discomfiture; he was unhappy and wished to return

home, a request that was, understandably in the circumstances, denied.

Some hours before this decision was taken in Constantinople Admiral Milne

had, in response to an urgent entreaty from Cheetham in Cairo, ‘in view of

anticipated movement of Turkish troops and attempted blocking of Canal’

detached the cruiser Black Prince to

remain at Suez.

With the British therefore expecting trouble in Egypt and the Russians similarly

anticipating Turco-German operations in the Black Sea the opportunities for

Enver and his cohorts to achieve strategical surprise were limited. In addition,

when the plans for the mooted Black Sea landings became more widely known in

Turkish military circles they ran into internal opposition. The Assistant Chief

of Operations, Major Sabis, complained that the Russian Black Sea fleet would

first have to be destroyed to ensure the safe passage of the slow Turkish

transports on their 300 mile trip; Sabis’ objection was duly noted. In case

this was not sufficient to discourage the Germans, the Major also warned the

Turkish officers who were working with Souchon ‘not to show our naval strength

as being more than it is.’

He did not have much to worry about: the condition of the Turkish fleet was so

appalling that Souchon suspected it had been the deliberate policy on the part

of the Limpus’ mission to maintain the fleet in the lowest possible fighting

condition.

But Souchon, by his vigorous desire for action, which went counter to the

Ottoman intention of remaining neutral for as long as possible, fell into a trap

of his own making. Now, as head of the Ottoman Navy, the onerous duties and

responsibilities of the task virtually chained him to the Corcovado where he complained, in long letters to his wife, of his

inability to get at the Russians and bemoaned that if he had really wanted to do

nothing he would, after all, have steamed to the Adriatic when being pursued by

the British and there joined the supine Austrian fleet.

The realization soon dawned upon him that, appearances to the contrary, the

Turks were effectively in control; Souchon could not hope to roam the Black Sea

in his battle cruiser looking for a scrap with the Russians while always

counting on being able to fall back, if necessary, and obtain sanctuary in the

Straits by the grace of a still neutral Turkey. If he provoked the Russians

against the wishes of the Turks and attempted to return to his safe haven the

Turks could disavow his actions as those of an ‘insubordinate troublemaker’

and possibly bar his passage.

Djemal’s ploy had worked for, while Souchon could, at any time, be disowned,

Raouf, if he had assumed command of Goeben,

most certainly could not.

When Mallet eventually returned, the Ambassador too was trapped by the

belief that his good offices still carried weight at the Porte. Beaumont’s

conflicting telegrams had estranged opinion in the Foreign Office where, as in

the Admiralty, Turkey had almost been given up as lost. The Turks were running

rings around the Chargé; Mallet thought he could reverse this. Ryan was not

alone in feeling relieved when Mallet arrived back late on the 16th and

‘scored one immediate success by obtaining permission for the outward passage

through the Straits of British ships with cargoes from the Black Sea.’

Mallet had argued, with Bompard supporting him, that Grey’s warning for

British ships to leave Turkish waters would be construed as indicating the

intention of Britain to attack Turkey at once and would, therefore, cause panic

in Constantinople.

Grey replied that the Turks, by detaining a number of British merchant ships,

had raised fears that they intended to seize them; however, he added, ‘if

there is no ground for such apprehension, and Turkey will give ordinary

facilities for British merchant vessels, you have full discretion to instruct

British shipping everywhere to proceed as usual.’

About 70 of the 80 ships in the Black Sea were thus able to escape the danger of

immobilization as Ryan, who kept a card index of the ships, played, late at

night, ‘a sort of game of patience’ of the ‘ins’ and ‘outs’.

The quandary of Turkey was raised once more in the Cabinet which met at

noon on Monday 17 August. For Churchill the Goeben

affair was an affront on two counts: he had personally drafted the early

operational telegrams to Milne and could not therefore escape a share of the

responsibility for the escape; and second, if Turkey did join the Central

Powers, the impression would be that the incident which had finally tipped the

scales was his pre-emption of the two Turkish dreadnoughts. ‘Turkey has come

to the foreground,’ Asquith wrote to Venetia Stanley of the Cabinet

discussions, ‘threatens vaguely enterprises against Egypt, and seems disposed

to play a double game about the Goeben

& the Breslau. Winston, in his

most bellicose mood, is all for sending a torpedo flotilla thro’ the

Dardanelles — to threaten & if necessary to sink the Goeben

& her consort.’ Crewe, the Secretary of State for India, and Kitchener

both urged caution: let Turkey strike the first blow, they argued, to avoid

upsetting the Muslims. Asquith agreed.

As he was getting nowhere, Churchill then protested to Grey of the ‘extremely

unsatisfactory’ situation: not only had the repatriation not taken place but

‘probably the whole of the German crews are still on board’, a condition

which resulted in two British battle cruisers ‘which are urgently required

elsewhere’ having to watch the Dardanelles.

With Crowe’s memorandum of the previous day still fresh in his mind,

Grey might possibly have been convinced by Churchill’s plea to adopt a more

strident tone; however events at Constantinople signalled a return to a more

cautious, pragmatic policy. When Limpus delivered Churchill’s private appeal

to Enver on the 17th it was, apparently, well received though the Pasha promptly

‘went sick’ and disappeared from sight. Mallet nevertheless telegraphed that

‘Minister of War is delighted with Mr Churchill’s message, and told Admiral

Limpus that he realised force of his arguments, and would answer it’

— although it was probably to avoid doing just that which accounted for

Enver’s sudden indisposition.

In the meantime, Enver delegated the task of deflecting the British to Djemal;

the Turks could not allow the British, through the agency of Churchill’s

‘personal appeal’ or otherwise, to seize the initiative. That evening, with

Enver safely out of sight, Djemal complained to Mallet ‘that British Commander

has informed forts at Dardanelles in writing that if German ships come out,

forts will be bombarded.’ Having seen Captain Kennedy only the previous

afternoon Mallet found it difficult to believe that Kennedy could be capable of

so impolitic an action: nevertheless Djemal’s complaint was serious enough to

warrant being relayed to London.

Captain Kennedy did, in fact, send a letter to the Commandant of the Turkish

forts but this was not until the following day – 18 August – and was a

simple inquiry whether Goeben and Breslau were ‘now Men of War of the Ottoman Empire; and where the

German officers and men are, who were in those ships when they entered the

Dardanelles, and under what conditions they are at present.’

When it arrived at the Foreign Office at 3.25 on the afternoon of 18

August Mallet’s telegram immediately set alarm bells ringing. Rear-Admiral

Troubridge was scheduled to take over from Captain Kennedy that very day and

Grey, worried that Troubridge might get ‘a too exciting report of the

situation’ from Kennedy, inquired of Churchill ‘no doubt you will instruct

Troubridge not to take hostile action against Turkey, unless etc…’

Orders were sent at once to Troubridge not to show hostile intentions to Turkey

but to prevent Goeben and Breslau leaving

the Dardanelles and to watch events without resorting to threats,

while Mallet was informed that evening that these orders applied only so long as

Turkey maintained her neutrality.

In an effort to temper this warning, Grey also authorized that – as soon as

the French and Russian Ambassadors had received similar instructions from their

Governments – an assurance of Ottoman territorial integrity could be delivered

at the Porte. When Mallet did so the Grand Vizier,

was

much impressed and relieved. He said that it would help him enormously. He

assured me that present crisis would pass, and that I need have no fear lest

Turkey would be drawn into hostilities against us or Russia. I am convinced of

his absolute personal sincerity.

For

what it was worth, Said Halim also claimed to have protested against the action

of Breslau in boarding British and French ships at the Dardanelles,

which he admitted was a breach of neutrality that he deeply deplored, and he

repeated, once more, the dubious assurances given so freely to Beaumont: neither

of the German ships would be allowed into the Black Sea or Mediterranean. With a

new envoy to deceive afresh, Said Halim then returned to the pre-emption of the

Turkish ships on which he had blown hot and cold with Beaumont but which he now

maintained had been the cause of the crisis. Despite this, Mallet held out great

hopes that, although the situation was delicate, with patience and no

precipitate action, it may yet be saved. ‘Unfortunately’, Lancelot Oliphant

minuted, ‘the whole Turkish Government is not incorporated in the person of

the Grand Vizier.’

If anything, Said now regretted putting his signature to the alliance on

2 August; indeed, he now claimed to have been duped by the Germans, who had

misrepresented the disposition of Bulgaria. The Grand Vizier still favoured the

creation of a four-power Balkan bloc which, he maintained, had more to gain by

remaining neutral; but Said could not convince his more rabid colleagues.

Instead, four options were canvassed: one, the Bulgarians should be persuaded to

mobilize; two, if they refused, a Roumanian-Bulgarian-Turkish defensive bloc

should be established; three, a four-power bloc should be created which would be

– against the wishes of the Grand Vizier – offensive in character; four, if

all else failed, a defensive alliance with the Greeks. In furtherance of this

objective, talks were reopened with the Bulgarian and Roumanian governments.

Talaat travelled to Sofia where he signed a treaty with the Bulgarians the

existence of which was kept secret even from Wangenheim, who only learned of it

the following December. The first four articles of the treaty pertained to the

customary promises of friendship, territorial integrity and mutual action of

both parties in case of attack by another Balkan state. The effect of all this

was, though, diminished by Article V which made Bulgarian action completely

dependent upon an ‘adequate guarantee’ from Roumania that she would not

interfere.

In the circumstances, it is difficult to see what form this guarantee could have

taken.

Talks were also re-opened with the Greeks, ostensibly on the islands

question. In Bucharest on 22 August Greek ex-Premier Zaimis and Nikolaos Politis

from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs met Talaat and Halil. Immediately Greek

fears were raised that Talaat, under the tutelage of Berlin, was intent on

forming a Turkish-Bulgarian-Roumanian bloc while securing Greek neutrality. As

the futile discussions dragged on the Greek delegates became aware of persistent

rumours that Turkey would launch an attack against Greece to coincide with a

Bulgarian assault against Serbia. It was certainly known that Talaat had been

involved in discussions with the Bulgarian Government, the purpose of which, it

was assumed, involved an agreement for concerted action.

Mallet believed that the Turks had been influenced by Wangenheim whom Mallet

believed was pressing for Greek neutrality. Wangenheim’s real object, Mallet

informed Grey, ‘has been always to induce Turks to declare war on Russia or to

bring about situation which would make war inevitable.’ A neutral Greece would

be unable to assist in Allied landings ‘at the Dardanelles if war broke out

between Turkey and Russia, and if we were involved.’

Mallet’s surmise was accurate: by reaching an accommodation with

Greece, Enver hoped thereby to remove an obstacle in his quest to precipitate

action against the Russians. Talaat eventually left Bucharest on 31 August,

leaving Halil to conduct the negotiations. On his way back to Constantinople

Talaat stopped at Sofia to try to persuade the equivocating King Ferdinand of

the need for Bulgarian co-operation but, citing Austrian reverses against Serbia

and Roumania’s ambivalent attitude, Ferdinand again refused to commit himself.

Bulgaria could not attack Serbia for fear of drawing in Greece and Russia

against her. Upon reaching Constantinople Talaat decided on a new approach: on 6

September he informed Wangenheim that, failing a Greek declaration of

neutrality, Halil would be recalled and the negotiations suspended. Talaat

demanded that further German pressure should be exerted on Athens and the Greeks

warned that the islands question would become a casus

belli if they failed to issue the declaration. The Germans went so far as to

have their Minister in Athens sound out Streit, but the Greek Foreign

Minister’s violent reaction confirmed German fears that any ultimatum would

push the Greeks into the Entente camp. Instead, any pressure emanating from

Berlin was directed back at Talaat: he was instructed to stop making waves with

Greece and, if he must attack someone, attack Russia — a prospect Talaat

viewed with something less than equanimity. At the same time, the

anti-interventionist group at the Porte, aware of the real reason for the Greek

negotiations, preferred to adjourn the discussions rather than reach a

settlement. So long as the dispute with Greece remained, they believed, the

scope for military adventures elsewhere was considerably reduced.

Halil was ordered to suspend negotiations in Bucharest while ‘Turkey made a

proposal to Greece, believed to be at the instigation of Germany and thoroughly

insincere, for a neutrality agreement by which neither should take part in the

war.’

More time had been bought by the Turks.

Mallet’s opinion, that the situation could still be saved, was one he

was to hold in increasing isolation. Grey, who was beginning to waver, would

have been satisfied with Turkish neutrality; yet although his naturally

phlegmatic nature would allow him to be swept along by the sanguine messages

coming out of Constantinople, no-one in London seriously talked of saving the

situation. It would be a mistake, also, to think that Mallet was completely

taken in; rather, in the opinion of Ryan, ‘if he had a fault it was that he

was too mercurial, oscillating between the deepest depression and comparative

optimism.’

Certainly, the optimism of Mallet’s first dispatches was soon qualified by his

warning that, to avoid any misunderstanding in view of the effusive comments of

the Grand Vizier, the situation was still grave. In the first intimation that

the Dardanelles would be a prime target, should the situation deteriorate,

Mallet warned that he:

should

like to make it clear that…presence of British fleet at Dardanelles is a wise

precaution in view of possibility of coup d’Etat with assistance of Goeben and complete control, exercised by military authorities under

German influence. It is for His Majesty’s Government to consider how far

forcing of Dardanelles by British fleet would be an effective and necessary

measure in influencing general outcome of war should situation here develop

suddenly into a military dictatorship.

As already mentioned, at the regular meetings in Said Halim’s palace,

the Minister of Marine had been deputed to deal with the British Ambassador

(while Djavid drew the French); their aim was to devote themselves ‘to remove

any suspicions [Mallet and Bompard] might have as to our alliances.’

Djemal got to work quickly. Mallet reported him as being ‘heart-broken at the

loss of his ships’, and that he begged to have Sultan

Osman returned at least. Djemal ‘solemnly assured’ Mallet that Turkey

had not thrown in her lot with Germany, that he would get rid of the German

crews as soon as possible, and that he was impatiently awaiting the return of

the transport Reshid Pasha from

Newcastle with the Turkish crews.

The declaration of Ottoman integrity was, the Minister admitted, already having

a good effect and he was glad Mallet had returned as he (Djemal) was ‘alone’

and would now work with Mallet towards the restoration of good relations with

Great Britain. The Pasha did his job well. As with the Grand Vizier, Mallet was

convinced that Djemal was ‘absolutely sincere’ and he urged Grey to prompt

Churchill to send a ‘sympathetic and friendly message’ to Djemal, which he

was sure would be well received; but, he added knowingly, ‘it would be as well

to avoid in such a message any mention of money payment.’

|