|

Mallet’s

arrival also coincided with Djemal Pasha’s artless approach to General Wilson

— the Governor of Constantinople had just assured the receptive Wilson that,

unfortunately, ‘The Turks could not now change their military teachers

(Germans), but in all else, in finance, administration, navy, and reforms they

wished to be under English guidance.’

To head this renascence in British prestige and influence there now

arrived as His Britannic Majesty’s representative to the Sublime Porte Sir

Louis du Pan Mallet. Ryan was not overly impressed, initially, by what he saw:

‘No man could have been a greater personal contrast to Lowther. Mallet was a

bachelor, very much of a dilettante in appearance, very quizzical, highly

intelligent, as supple as his predecessor had been unbending, and intent on

conciliating the Young Turk leaders by friendliness and charm. He did not

impress me greatly at first, but he grew on me very much when we became

intimate.’

Against Mallet there stood the imposing figure of the German Ambassador, Baron

von Wangenheim, who was described by his American colleague as having ‘a

complete technical equipment for a diplomat; he spoke German, English and French

with equal facility, he knew the East thoroughly, and had the widest

acquaintance with public men. Physically he was one of the most striking persons

I have ever known…He was six feet two inches tall; his huge, solid frame, his

Gibraltar-like shoulders, erect and impregnable, his bold defiant head, his

piercing eyes, the whole physical structure constantly pulsating with life and

activity…’

Unfortunately, if understandably, it did not take long for the new Ambassador to

come to regard Fitzmaurice as invaluable. Within a fortnight Mallet was

informing Grey that he ‘shall not be able to do without’ Fitzmaurice whose

knowledge was so extensive and ‘his means of getting it so varied that he is

indispensable.’ The British balloon that had so recently been blown up was

pricked when Mallet added, ‘I do not believe that his presence here will

injure any chance of getting good relations with the Young Turks. On the

contrary it is more likely to help me.’

Of more immediate concern however, Mallet soon became embroiled in the affair of

Liman von Sanders and the German Military Mission which, of necessity, also

highlighted the work of Admiral Limpus at the Turkish Admiralty.

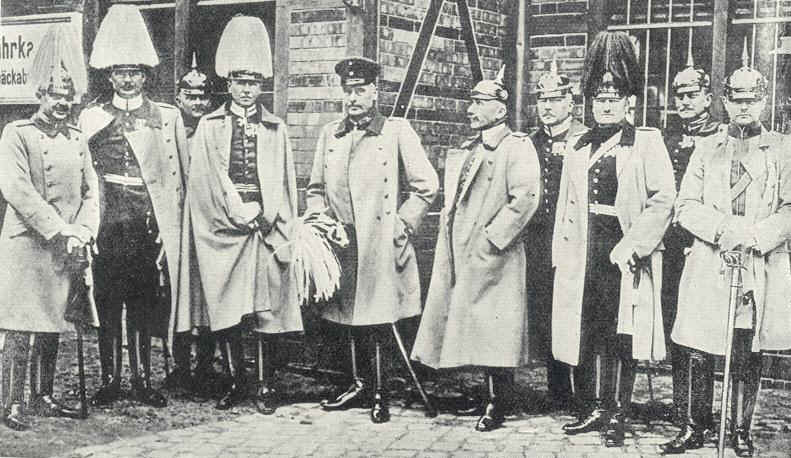

Liman von Sanders (centre) and his Staff

The

genesis of Liman’s mission was to be found in the poor performance of the

Turkish Army in the First Balkan War which, in turn, was perceived to reflect

badly upon the German military instructors and also upon German arms. The remit

of the previous incumbent, General Colmar von der Goltz, had been confined to

areas such as the organization of manoeuvres and inspection of troops while his

mission, as often as not, attracted the wrong type of German officer who took

every opportunity to impress upon the Turk his own view of his undoubted

superiority. The defeat of the Turkish Army was felt even more humiliatingly as

the Serbs and the Greeks in particular relied upon French training and arms.

A French military mission, operating in Athens under General Eydoux, had made

great strides in raising the efficiency of the army to a level at which the

Greeks made an attractive partner for the Balkan allies; as early as January

1913 German inquiries had been initiated to ascertain the conditions under which

Eydoux served. By April, when the temporary lull following the fall of

Adrianople afforded a suitable breathing space, Shevket’s thoughts turned to

strengthening the defences of Constantinople against a renewed Bulgarian attack.

He therefore approached the German Military Attaché, Major von Stempel, to

request that a suitable Prussian officer be found to formulate new plans for the

defence of the capital. Shevket then took up the matter further on 26 April in a

long interview with Wangenheim when it transpired that what the Grand Vizier had

in mind was a complete reorganization of the army under the responsibility of a

large scale military mission with, if required, a German general in actual

command of a Turkish Army corps.

The German Ambassador became a thorough-going convert to the idea,

accepting fully that ‘According to Turkish ideas, the Army was the deciding

factor in the state.’

His conversion owed not a little also to his belief that the Entente Powers had

well advanced plans for the partition of Asiatic Turkey which, as yet, Germany

was in no position to capitalize on. In that case, it was in Germany’s

interests to postpone a scramble amongst the Powers and the best way of

achieving this aim was to ensure that the Turks possessed a strong, well-trained

army. Wangenheim’s official request for ‘a leading German General’ was

telegraphed to Berlin on 22 May 1913. Two days later, at the marriage of the

Kaiser’s only daughter (which was attended by King George V and the Tsar),

Wilhelm informed his illustrious guests of the Turkish request. To King George

it was ‘quite natural that they should turn to you for officers to reorganise

their army’, while – apparently – the Tsar, also, was content, believing

it was ‘necessary very strongly to fortify the Chatalja Line, so that the

Bulgarians could not cross it.’

It seems, however, that Wilhelm had left his guests with the impression that the

new mission would simply replicate the work of von der Goltz.

The Kaiser placed a greater reliance upon Turkey as a military ally than

many of his officials and there was little likelihood that he would not accede

to the Turkish entreaty; all that was required was to find a suitable officer.

Nevertheless it was not until 30 June that the Chief of the Military Cabinet

reported ‘A general has been discovered – though not without difficulty –

who states he is prepared to undertake that duty. He is Lt-Gen. Liman von

Sanders commanding the 22nd division at Cassel, a brilliant divisional

commander, who would be specially fitted for the position in every way…’

Although, for the time being (the Second Balkan War having broken out), it was

considered inappropriate for Liman to appear at the Porte, once peace had been

concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Bucharest, Wilhelm made it clear

that he wished the matter to proceed with dispatch. Negotiations concerning the

position, status and remuneration of the mission continued throughout September

and October, until finally the resolution of the separate Turco-Bulgarian talks

removed the last obstacle. On 28 October, in Berlin, Liman von Sanders signed

the draft agreement by which he became commander of the Turkish First Army

Corps.

Three days later the British Military Attaché in Berlin, Lieutenant-Colonel

Alick Russell, reported that there no longer seemed to be any doubt that a new

German Military Mission would be sent to Constantinople, and that it would ‘be

granted unlimited powers to carry out it’s [sic]

work in Turkey. It is a matter for wonder by whom such powers are guaranteed and

in what directions they extend.’ Russell also confirmed the universally good

impression of Liman.

By early November Baron Giers, the Russian Ambassador at the Porte,

suspected that there was a fundamental difference between the missions of Liman

and von der Goltz; a suspicion which was confirmed on 6 November when the

Russian Naval Attaché in Constantinople became aware of the actual details of

the agreement.

The following day, with Sazonov again absent, his understudy Neratov quizzed the

German Chargé in St Petersburg about the information he had just received from

a secret source in Turkey.

Until 17 November, when Sazonov returned, Neratov conducted the talks with the

aim of defusing the issue. Neratov maintained that the siting of the mission on

the Balkan front – say, in Adrianople – would be a far less serious matter

for Russia than to have a German mission in Constantinople or the Dardanelles.

It was only on the 17th that matters took a turn for the worse — the Russian

Prime Minister Kokovstov, who had been in Paris conducting financial

negotiations, planned to break the return journey in Berlin to convey to the

Kaiser his gratitude for the order of the Black Eagle which had been recently

bestowed upon him. This seemed an ideal chance to broach the dispute in an

informal manner and clear up any misunderstandings. In a meeting with

Bethmann-Hollweg and Wilhelm, Kokovstov was surprised when Wilhelm referred to

the Tsar’s apparent agreement to the mission, expressed at the wedding in May;

in any event, Wilhelm tendentiously pointed out, to limit Liman to the same

conditions applying to von der Goltz would inevitably produce the same result.

Liman must adopt a far more active rôle.

Upon Sazonov’s return, Bethmann-Hollweg was soon disabused of any

notion that the Russians would calmly acquiesce: the Russian Foreign Minister

was ‘painfully disturbed’ by the question of the mission. That very month

the Russian Admiralty had called for an increased Black Sea building programme

with the eventual aim of acquiring a fleet of eleven dreadnoughts by 1919. Until

the dreadnoughts currently being constructed at such massive cost could be

completed, Russia was helpless. Worse, as Sazonov outlined to the Tsar, was

‘the potential gravity of a seizure of the Straits by a state less responsive

to Russian pressure than Turkey.’ Twice, during the Turco-Italian war the

Straits had been closed: on the first occasion, as grain could not be exported,

prices fell by 15 to 20 per cent and banks refused to handle bills of exchange.

The second closure resulted in a massive reduction of the trade balance and an

increase in the bank rate.

The German response was one of great surprise to the strong Russian

objections. As the German Foreign Minister later explained to the British

Ambassador, the first mention of the subject had been by Wilhelm to the Tsar

and, or so it was believed, Nicholas ‘rather encouraged the idea.’ It had

been ‘unfortunate’ that the matter had not been discussed when Sazonov was

in Berlin but this was only because Bethmann-Hollweg had thought the affair was

all arranged and ‘that as it was only a matter of another German officer

succeeding General von der Goltz [he] had not thought it worthwhile to discuss

it…There had been no bad faith in the matter at all…’

Despite the fact that the Germans could always fall back on the convenient

excuse that the Turks had, themselves, requested the mission Kokovstov was still

able to make some headway with Bethmann-Hollweg. Indeed, Kokovstov’s

interviews with Bethmann-Hollweg had led the former to the conclusion that this

mission had grown both in functions and numbers after the Chancellor had

originally agreed to it, but without his subsequent knowledge. Following his

discussions with the Chancellor, Kokovstov believed that Bethmann-Hollweg had

accepted, in principle, either that Liman should be allowed to reside in

Constantinople, but with modified powers or, preferably, that he should have

full powers and reside in Adrianople. However, rather than helping to allay

Sazonov’s doubts, the Prime Minister’s opinion that matters had proceeded

without Bethmann-Hollweg’s full knowledge merely reinforced Sazonov’s belief

that there were two policies in Berlin: one formulated by the Chancellor and the

other by the military and the Court.

If Sazonov needed any proof of this, it was soon provided: despite the

progress Kokovstov thought he had made, on 23 November he was informed that the

negotiations regarding the mission having been concluded, they could not now be

altered.

As a sop it was proposed that, when he arrived, Liman could examine the

situation on the spot to see whether a transfer to Adrianople or Smyrna would be

possible though it was felt that this would not be the case for the simple

technical reason that all the military schools were situated in Constantinople;

besides the very mention of Smyrna aroused French hackles raising as it did the

question of a German presence in the eastern Mediterranean. It was therefore no

surprise when the French Foreign Minister informed Sazonov that he agreed

entirely with the Russians: while Liman at Adrianople was just barely tolerable,

Liman at Smyrna was out of the question.

British reaction was muted. Hugh O’Beirne, the British Chargé

d’Affaires at St Petersburg, reported privately to Nicolson that it was ‘not

at all surprising that Sazonow should be very seriously upset by the arrangement

just come to by Turkey with regard to the engagement of German officers having

executive command. When one thinks what Constantinople means to Russia it is

certainly an intolerable thing for her to see the town virtually in the hands of

a German commander. But much as I sympathise with Sazonow his attitude seems to

me to be one merely of impotent annoyance. He says he has used strong language

at Berlin. What good will that do?’ O’Beirne complained that Sazonov had no

definite ideas at all as to how to reply to the German coup and that, in his

wilder moments, he talked of having a Russian general in command of the Turkish

force at Bayazid;

or else Russian officers could be appointed in Armenia. In the opinion of the

Chargé the ‘only effective reply’ would be to have one or two warships

stationed at Constantinople which would be capable of landing a detachment, when

called upon, to protect the Russian Embassy: ‘But as Russia is certainly not

prepared to take any decided course of that kind any demands for compensation

which she may make of Turkey will probably prove quite futile.’

The problem for Grey was that, while admitting that the other Powers could, in

view of the German action, demand similar advantages ‘to compensate and

safeguard their own interests’ he could not see how these could be obtained

‘consistent with the maintenance of Turkish independence’.

The official response was provided by Grey who conceded that the German

command at Constantinople was ‘sufficiently disagreeable for all other

Powers’ and added that it was a matter of intimate concern for Russia and,

therefore, it was ‘not a question in which we can be more Russian than the

Russians.’ Fear of British action would weigh far less heavily on the German

Government than apprehension over how far the Russians were likely to take the

matter.

Nicolson, however, wrote, privately and more illuminatingly, that ‘we are

rather puzzled as to what to do in respect of the appointment of the German

General’. Personally, he would confine himself to ascertaining Liman’s

precise functions and then pointing out to the Turks the ‘dangers to which

they are exposing themselves by placing the garrison at Constantinople under the

command of a foreigner.’ One obstacle, clearly anticipated by Nicolson,

revolved around the widespread antipathy with which Sazonov was viewed at the

Foreign Office:

The

difficulty always in dealing with Sazonoff is that one never knows precisely how

far he is prepared to go. Though we are quite ready to admit that the

appointment, if it be really of the character which we are given to believe, is

of a very serious nature, still we should look rather foolish if we took the

question up warmly and then found that Sazonoff more or less deserted us. In

fact there is a certain disinclination on our part to pull the chestnuts out of

the fire for Russia…

This

disinclination was heightened three days later with the receipt of a dispatch

from Mallet that the ‘Advantages of a friendly settlement appear to be very

great. If our representations here meet with a rebuff question of compensation

must arise…otherwise it would be better not to take so formal a step. Force of

circumstances might possibly compel Russian Government to ask for opening of

Straits, although this is unlikely…I cannot suggest any special compensation

for which we could ask, Admiral Limpus already having command of the fleet, a

point which is likely to be made much of by Turks and Germans and which is

theoretically a good one’.

In view of Nicolson’s apprehension regarding the danger for Turkey of

having her troops under foreign command, the information from Mallet that the

Turkish navy was already under foreign command, and British as well, thoroughly

disconcerted the Permanent Under-Secretary: ‘I had no idea’, he minuted

incredulously, ‘that Admiral Limpus commanded the fleet. I thought he was

merely there as an adviser and instructor. If the fact be as stated by Sir L

Mallet we are not on perfectly unassailable ground in demurring to the

appointment of the German General.’ When Nicolson, who promptly searched out

Limpus’ contract, discovered that, in addition to naval adviser, he was named

Commander of the Fleet, with a proviso only that he was not to perform active

service in time of war, the realization must have been disconcerting. ‘I do

not deny’, he was forced to argue ineffectually, ‘that there is a difference

between commander of an inefficient navy and that of C-in-C of the garrison of

the capital. Still a point could be made against us.’

Nicolson pursued the same line of reasoning when replying to Mallet, although he

did have the decency to alter ‘inefficient navy’ – which was as much a

slur against Limpus – to ‘a fleet which is hardly yet in existence.’

Grey was also obviously disquieted: ‘I did not realize the nature of Admiral

Limpus’s command’, he admitted, before adding, ‘We must certainly go very

carefully.’

Grey’s fears were quickly realized. O’Beirne discussed the matter on

8 December with the German Ambassador in St Petersburg, Count Pourtalès, who

could not understand what the fuss was about: Liman’s appointment was

analogous to Limpus’. Further, he maintained, Liman’s position was less important than von der Goltz who had been Inspector General

while Liman would merely command an army corps; ultimately, as a sovereign

state, Turkey was free to appoint whomsoever she chose. O’Beirne was aware

that Pourtalès had been making the most of the analogy of the British Admiral

and German General to Sazonov. It was, therefore, hardly a coincidence that

Sazonov was now complaining to him (O’Beirne) that the work of Limpus ‘was a

serious thing for Russia.’ The Chargé pointed out that the Turks were

determined to have a strong fleet to cope with the Greeks and, if the British

did not assist, it was ‘perfectly obvious’ some other Power would. If there

were any question of Turkey seriously threatening the Russian naval position in

the Black Sea the objection might have some validity, ‘but that was really too

remote a contingency to be considered at present.’

Sazonov’s temper was not improved when he became aware of the iradé

published in Turkey on 4 December which confirmed the details of the agreement

with Germany signed a week previously. The Foreign Minister, speaking to

O’Beirne about the matter ‘with greater seriousness and openness than on any

other occasion’ O’Beirne could remember no longer attached great importance

to the purely military aspect of the appointment. Liman, he argued, may very

likely not be more successful than von der Goltz with the Turkish army, but he

was ‘firmly convinced that the command of the First Army Corps will give

Germany such a complete political preponderance at Constantinople that other

Powers will find themselves definitely reduced to a secondary position in

Turkey.’ It was now ‘a test of the value of the Triple Entente’ and while

Germany may have weighed the chances of a conflict with France and Russia she

could not afford, if Britain became involved, the additional danger of a naval

war. The Entente Powers would have to take ‘a really decided stand’ and,

therefore, Sazonov was relying greatly on Britain. If Turkey refused to heed the

representations, Sazonov proposed to apply pressure by means of a financial

boycott, a refusal to agree to the customs increase, and a withdrawal of the

Ambassadors (upon which he was particularly insistent). To O’Beirne’s

objections on this point, Sazonov countered that once having withdrawn the

Ambassadors and to avoid complete loss of prestige even more active measures

must be taken; he provocatively suggested ‘the occupation of certain Turkish

ports.’

Threats of this nature made it all the more imperative that a solution be

found quickly, preferably involving Russo-German discussions, in the hope of

avoiding the problem posed by the presence of the British naval mission. There

seemed little likelihood of this when Mallet reported that the whole position of

Britain in relation to the fleet and the dockyard concession was ‘much dwelt

upon in the Press and in political circles’. Besides, if the intention of the

Entente in blocking Liman’s appointment was realized, it was entirely possible

that the Triple Alliance would be similarly obstructive regarding the command of

the fleet when Limpus’ two year term expired in April 1914. A further

complication was that Limpus, under the impression that his prospects for

advancement in the Royal Navy were suffering because of his Turkish duty, now

showed signs of not wishing to renew his appointment; indeed, he would do so

only if pressed. The only way around the recurrence of this obstacle was, in

Mallet’s opinion, for an officer to be chosen who would reach natural

retirement from the active list within the period of his Turkish tenure and so

would have nothing to lose by staying on, a suggestion which found little

sympathy in the Foreign Office. As Crowe pointed out, the task of organizing the

Turkish fleet required the best abilities of a first-rate officer, who was not

likely to be found among the candidates for early retirement.

Nevertheless, Mallet continued in his attempts to defuse the growing

crisis. To do so he used three separate arguments to try to influence Grey:

first, he spelt out the extent of Limpus’ power, which included the

‘absolute command’ of the Turkish fleet in peacetime — Limpus ‘could do

anything except break the law or exceed the budget.’ Second, Vickers and

Armstrong had just obtained a thirty-year concession to modernize the

Constantinople dockyard and construct an arsenal and floating dock in the Gulf

of Ismid, which made it all the more difficult for Britain to take a strong

line. Third, Liman’s command of the First Army Corps would be ‘entirely

innocuous to our interests.’

While the first two contentions were undeniably true, the last might have seemed

an optimistic judgment until it became clear that Liman’s powers were not as

great as first thought and did not, for example, extend to control of the

Straits. Grey however could not ignore the unrelenting Russian pressure,

as Sazonov pushed for a joint démarche at the Porte. Grey preferred a more

simple verbal inquiry, an option certainly preferred by Mallet who foresaw (in

addition to the riposte regarding Limpus) that joint action would only harden

the resolve of Germany and Turkey to resist. ‘Would it be possible’, Mallet

suggested, for the British Government ‘to attempt some kind of mediation on

the basis of an assurance from the German Government that the German General

will, after, say, one month here to study local conditions, propose either to

remove the command to Adrianople or be content with the position of adviser, or

some other expedient which Russia could accept?’

In anticipation of being able to offer the Germans a quid pro quo the Russian Ambassadors in Constantinople and London

approached Mallet and Grey with a compromise to try to break the deadlock:

Mallet telegraphed on 12 December that the Russian suggestion was for Liman to

remain in Constantinople as titular head of the mission while his assistant

became head of the Army Corps at Adrianople; then, on Britain’s part, the

headquarters of the naval mission might be transferred to Ismid and Limpus’

title changed to ‘Adviser’ when his term ended in April 1914.

Grey replied that he, too, had been approached regarding the relocation to Ismid,

adding, ‘if it is practicable and consistent with performance of his duties by

Admiral Limpus and if Turkish Government will agree, I not only will not object,

but will encourage the transfer, if it will help to a solution of difficulty

about German command.’

Unfortunately, no-one had yet quizzed Limpus as to the practicality of the

transfer and when Mallet eventually got round to this the Admiral pointed out

the obvious objection that, as the proposed dockyards and arsenal there had not

even been begun, he would command little more than a building site. Limpus

however did agree, reluctantly, for the new contract to refer to ‘naval

adviser’ whose duties ‘would comprise any service assigned to him by the

Turkish Government’ but felt obliged to stress – as if Grey needed reminding

– the delicate position of the naval mission in that the Turks, determined to

have a good navy, would simply turn elsewhere if Britain adopted an intransigent

tone or made difficulties when the contract expired.

Limpus was also upset to find that his one tangible accomplishment, the

successful outcome of the protracted negotiations leading to the Docks’

concession being granted to a British consortium, was now being used by one

Power to score points against another.

To complicate matters further (if that were possible) Mallet had also become

aware that the Turks had recently been involved in secret talks to purchase the

super-dreadnought building in England for the Brazilian navy, possession of

which would profoundly alter the naval balance in the eastern Mediterranean.

Unlike Lowther’s continual reports of secret negotiations for the purchase of

non-existent battleships this time there appeared to be substance in Mallet’s

information. Although such a ship would lend undoubted prestige to the work of

the naval mission it was also likely to result in the Turks adopting a more

forward policy.

Grey could do no more than hope that the Germans would agree to modify

both Liman’s title and position if that of Limpus were similarly modified and,

in looking for an indication that the Germans would be willing, the Foreign

Secretary believed that the reply of the Grand Vizier to the collective inquiry,

scheduled to be presented on 13 December, might present an opening.

Grey was fortunate that it was Mallet, and not Lowther, who now faced the

audience with Said Halim; indeed, Mallet’s conciliatory approach was

favourably commented upon by the German Embassies in both London and

Constantinople. The former reported to Berlin on 12 December for example that,

although known as a champion of the Triple Entente, Mallet’s attitude as shown

in his dispatches (which had been obtained by ‘confidential and secret

means’) was ‘thoroughly moderate and not calculated to decide Sir E Grey to

take part in any steps in Constantinople.’ The Germans, being particularly

well informed, were aware of the ‘extraordinarily strong pressure’ being

brought to bear by the Russians, backed up by the threat that the Russian

Government would be bound to regard Grey’s attitude in the matter as ‘a

touchstone for England’s feelings towards Russia’, while all the time

knowing that Grey’s policy was to avoid a breach with Russia. Unhappily, this

abundance of information was not enough to sway Wilhelm from his baser judgment:

the Russians were ‘scoundrels’ and Grey was a ‘donkey’ who was betraying

his country’s true interests. The Emperor’s lively marginalia displayed

slightly more prescience when he was informed that, for forms sake, Britain

would join in the collective representation at the Porte, but without Grey

himself ‘bringing strong interest to bear’ — ‘That will annoy the Grand

Vizier’, he gleefully noted.

On the afternoon of the 13th the three Entente Ambassadors took turns to

read an identical ‘questionnaire’ to the Grand Vizier, the main thrust of

which concerned a warning of the possible loss of Turkish independence and the

question of the control of the Dardanelles. Having told the representatives of

the Powers that this was none of their business, Said Halim asked the Russian

Ambassador to leave his copy of the questionnaire; Giers refused. When pressed

again two days later by Giers, the Grand Vizier declared that ‘the Straits,

the fortifications, and the preservation of order in the capital, are not within

the competence of the [German] General. These, as well as the declaration of the

state of siege, are directly dependent on the Secretary of War.’

Sazonov remained unsatisfied: as far as he was concerned the Entente itself was

now under threat. He complained to O’Beirne on 14 December that the matter had

provided ‘the first question seriously involving Russian interests’ in which

Russia had sought British support, ‘and therefore as furnishing a test of the

support which they can expect.’ Sazonov warned further that, if the Entente

suffered a defeat on the question, the Turks would conclude definitely ‘that

the strength lies on the side of the Triple Alliance’. The result then would

be that they would become intractable on the subject of Armenian reforms which

might lead to an uprising in that province which, in turn, would ‘necessarily

induce the armed intervention of Russia’; the result would certainly be war.

As Sazonov delivered this chilling warning, Liman and the first ten

officers of a projected party of forty-two were arriving at Constantinople.

Yet, despite the Russian’s dire prediction – which reached the Foreign

Office at 11.30 p.m. on 14 December – when Grey had a long conversation with

the German Ambassador the next day Lichnowsky could not but comment on how the

Foreign Secretary appeared to be in ‘excellent spirits’; though this could,

of course, also be accounted for by the prospect of the forthcoming holidays.

Grey believed that the main point at issue was whether Liman’s position

corresponded to that of von der Goltz or whether it was something entirely new.

Although, he admitted, this was personally a matter of indifference to him,

He

could not but fear, however, that if the powers granted to the German officers

now in Constantinople represented any considerable extension of their executive

functions, Russia might demand compensations in Constantinople in the form of

the transfer to her of a command in Armenia. Such a solution seemed to him to be

fraught with danger, as it might mean the beginning of the end — the beginning

of the partition of Turkey in Asia. He would do everything in his power to

prevent things taking such a turn, but in view of the excitement in St

Petersburg he could not guarantee that his efforts would be crowned with

success.

Inevitably,

Lichnowsky raised the question of Limpus, which, just as inevitably, Grey

parried: Limpus, he asserted, held the same position as his predecessor, whereas

Liman’s appointment was a significant departure from that of von der Goltz;

besides, Grey added (exhibiting his usual lack of strategic awareness), the

Russians ‘were much less touchy with regard to the fleet than with regard to

Constantinople.’ For his part, Lichnowsky maintained that, in Germany, little

importance was attached to the dispatch of the officers to Turkey and that, in

any case, it was improbable that a few officers could influence the course of

foreign policy in Constantinople. Throughout, the conversation had been

conducted in a friendly tone and Lichnowsky was left with the clear impression

that Grey found the whole affair ‘very unpleasant and exceedingly

embarrassing.’

Although signs began to appear that the German resolve was weakening, in

the days leading up to Christmas Sazonov continued to play a dangerous game. Sir

George Buchanan, the British Ambassador at St Petersburg, had now returned from

leave and Sazonov lost no time in warning him that irresoluteness – the

appearance of being afraid of war – would just as surely lead to war; however,

when questioned directly as to whether Russia would risk a war over the Liman

affair, Sazonov replied, ‘Certainly not.’

Similarly, when Goschen saw Jagow on Christmas Day the German Foreign Minister

was also keen to play down the whole affair. Jagow had just received a lengthy

communication from Wangenheim in which the Ambassador argued that the Russians

would have reacted badly whether or not Liman had been named to command the

First Army Corps, and, moreover, it was his opinion that the dual

responsibilities of training the Turkish Army and the command duties were too

onerous. Wangenheim suggested instead that Liman should be promoted to

Inspector, with his place in the First Army Corps being taken by a Turk, while

the German General Bronsart could command the army corps in Adrianople. He

envisaged however that the Turks would be loathe to agree to a higher command

for Liman as they were also in no mood to yield and that Liman himself, being a

‘passionate man’, would not take kindly to playing the part of a pawn.

Jagow was able to tell Goschen that, in addition to everything else, ‘the

Ottoman Government seemed rather inclined to make difficulties’ and, besides,

it had been the Turks themselves who had insisted Liman be given a slightly

superior position than von der Goltz as ‘the latter had, comparatively

speaking, failed owing to his not being in a position to enforce the necessary

discipline.’

With conciliation now in the air, it was to general chagrin that Sazonov

now proposed a joint démarche at Berlin!

When the Russian Chargé put this to Eyre Crowe (Grey being away on holiday) the

Assistant Under-Secretary decided it was time to get some firm answers: what,

exactly, did Russia want — the cancellation of Liman’s appointment or else

suitable compensation? If Turkey refused to accede, what coercive measures were

proposed? If Germany supported Turkish resistance to Russia, would the Russians

contemplate, as a last resort, war with the Triple Alliance?

It is not difficult to imagine the relief felt by Grey at being able to set

Crowe on the Russians and it was no surprise that Grey fully approved his

language. Goschen was informed on 2 January 1914 that, as far as Sazonov’s

proposed Berlin démarche was concerned, Grey did not want the Germans to know

that the request had been made and that Britain had rejected it. It would be, he

argued, ‘neither moral nor expedient to make capital at Berlin out of having

refused a Russian request. But I must tell Lichnowsky when I next see him that

the Russians are more concerned than ever and must be satisfied somehow…I

don’t believe the thing is worth all the fuss Sazonow makes about it; but as

long as he does make a fuss it will be important and very embarrassing to us:

for we can’t turn our back upon Russia.’

|