Contact Information

Flamborough Marine Limited

The Manor House

Flamborough

Bridlington

East Riding of Yorkshire

YO15 1PD

United Kingdom

Telephone:

01262 850943

International:

+44 1262 850943

E-mail:

gm@flamboroughmarine.co.uk

For authentic hand-knitted Ganseys, Gansey Knitting Kits, Armor Lux

striped cotton Breton shirts and a range of traditional wool knitwear

from Le Tricoteur (the original Guernseys) and Armor Lux of France

Flamborough Marine Limited : Traditional Knitwear & Hand-Knitted Ganseys

The Manor House, Flamborough, Bridlington, East Riding of Yorkshire. YO15 1PD

Telephone: 01262 850943 [International: +44 1262 850943]

E-mail: gm@flamboroughmarine.co.uk

Few occupations are more at the mercy of the wind and weather than fishing. And it was the

practical requirement for warm yet unencumbering clothing that prompted the development

of a fascinating tradition in fishermen’s sweaters, variously known as jerseys, Guernseys and

Ganseys.

It is likely that the word ‘jersey’, used to describe a knitted garment, owes its derivation to the

name of the largest of the Channel Islands, where worsted spinning was once a staple

industry. Over a period of time, the close-fitting garments knitted in worsted-spun yarn made

in Jersey, and favoured by sailors and fishermen, became known as jerseys.

Similarly, the neighbouring island of Guernsey gave its name to the classic square-shaped

wool sweater, which was designed with a straight neck so that it could be reversed. Gansey, a

term which crops up in the writings of both Samuel Beckett and James Joyce, is a dialect

variation of Guernsey.

Until the coming of the machine age in the nineteenth century, most industries were small-

scale and craft-based. As early as 1589, however, the invention of the knitting frame by

William Lee, a brilliant Nottinghamshire clergyman, had put into motion the gradual migration

of hosiery manufacturing from the domestic setting to the factory. The uptake of machines

was uneven, with pockets of the knitting industry, such as the famous knitters of Dent who

made small items on short needles, resisting change for many years.

The production of heavier gauge knitwear remained a largely domestic activity until much

more recently, with women knitting for entire families well within living memory. Every village

shop would have boasted a section devoted to knitting yarn, and the market towns would have had at least one thriving wool shop.

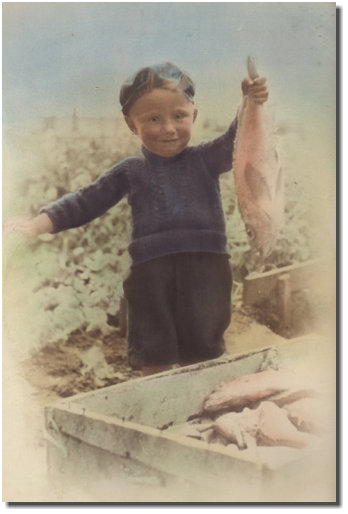

The isolated communities along the rugged British coastline were, by necessity, even more self-sufficient than those further inland. In the poor

fishing communities, families could ill afford the luxury of goods imported from the outside world. Women knitted for their sweethearts,

husbands and children. At a time when resources were scarce, outgrown clothes were passed down and adults’ garments cut down and remade

for children.

Visitors to the Yorkshire fishing ports such as Whitby and Filey and tiny villages such as

Seahouses on the rugged Northumberland coast, reported seeing women sitting in their

doorways busy with their needles. Never wasting a moment that could be used to earn an

extra penny, women worked late into the evening by the light of rush lamps, knitting the

navy-coloured yarn more by feel than by eye.

Although the classic Guernsey sweater remained plain (some Guernsey parishes did,

however, have their own patterns), the stitch patterns used became more complicated the

further north the garment spread, with the most complex evolving in the Scottish fishing

villages. These elaborate patterns came south with the Scottish herring fleet, as the women

folk followed their husbands down the coast to gut the fish. Thus the pattern known as

Whitby flag is in fact an interpretation of a Scottish design.

Young women, who had received little formal education, would develop the ability to

memorize complicated patterns, which were passed down from mother to daughter,

gathering new variations with each generation. The garments were made on five or more

needles, often called “wires” or “pins”, so as to be seamless. It was not unusual for men,

too, to knit ganseys. Knitting was a natural extension of the familiar tasks of making and

mending fishing nets, routine jobs which required considerable dexterity.

Tightly knitted in worsted yarn the fisherman’s Gansey was virtually wind-proof and water-

proof. As these working garments were rarely washed, there is no doubt that a layer of filth

would have added to the general protective effect. It is consoling to learn that fishermen

had “Sunday best” Ganseys which, being decidedly more fragrant, were worn for church

and on high days and holidays.

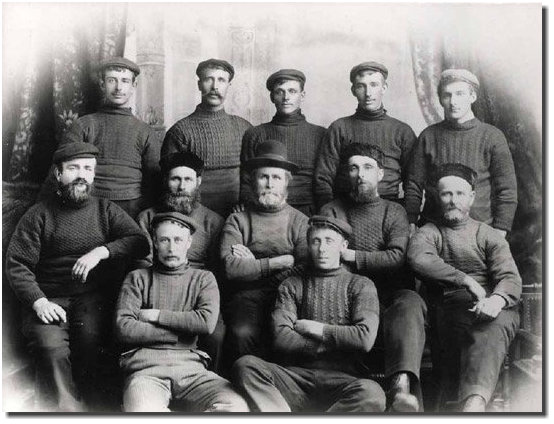

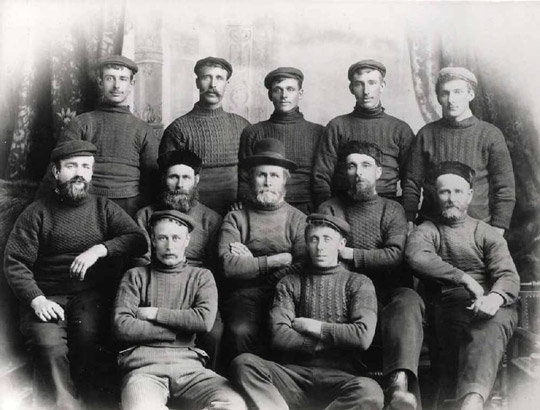

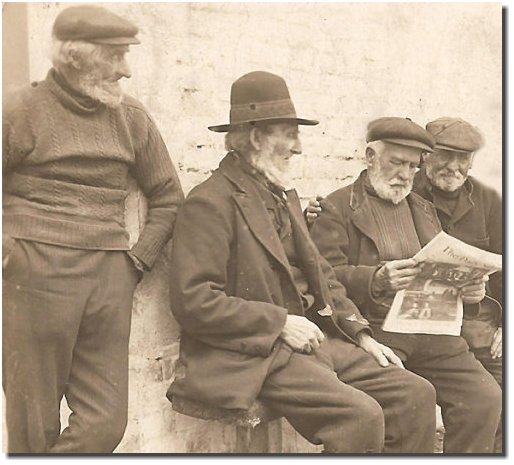

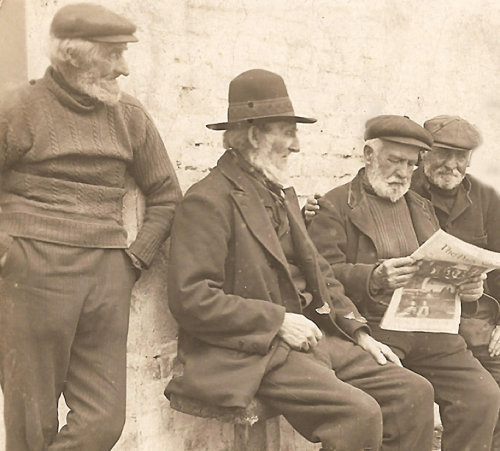

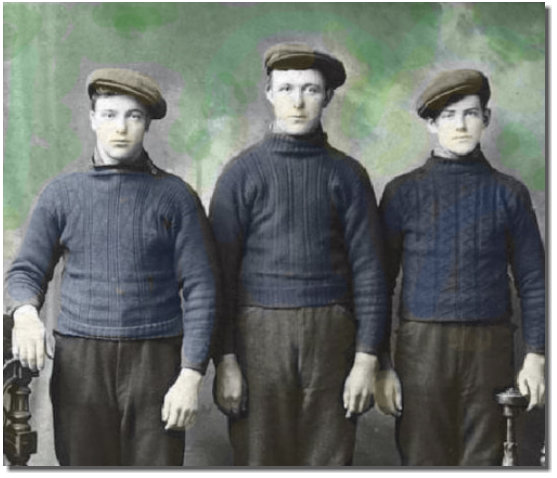

Many venerable Ganseys appear in the sepia toned photographs taken by the well-known

Whitby photographer Frank Meadow Sutcliffe from 1880 to the turn of the nineteenth

century. Prints made from Sutcliffe’s original glass plates provide a fascinating insight into

the clothing of ordinary working people. The characteristic, almost tubular, shape of the fisherman’s Gansey was dictated by practicality. The

welt, neck and cuffs were knitted tight so as to keep out winter blasts. According to hearsay, so tight were the Ganseys knitted for the

unfortunate children of one fisherman that, when the garments were pulled over their heads, the children’s ear lobes bled.

The cuffs, also made to be close-fitting, generally ended short of the wrist to avoid impeding the hands and becoming soaked with sea water as

the men worked. The close fitting design also helped to reduce the chances of the hem or cuffs becoming caught on pieces of equipment or

tackle, a mishap which could prove fatal. As time took its toll on the cuffs and elbows, the lower half of the sleeves could be unravelled and re-

knitted with new yarn. Garments made in various shades of blue, ranging from deep navy to a hue faded with age, were a common sight.

The upper part of the body was knitted more densely than the lower part to provide extra warmth, and it was on the yoke and upper arms that

the knitters had the opportunity to show off their knitting skills and to elaborate on the basic stocking stitch with numerous variations. For

detailed records of the many local interpretations of traditional fishermen’s jerseys, we are indebted to the tireless efforts of Gladys Thompson,

who, in the 1950s, pencil and paper in hand, scoured the fishing ports on the east coast—from Sheringham and Cromer in Norfolk as far as

Upper Largo in Fife.

Her quest, fired by a determination to preserve for future generations patterns which were seldom written down, took her down the narrow

harbour ginnels (passages) and into the cramped fishermen’s cottages, where often a single room served as kitchen, bedroom and living room,

with an attic above for storing and mending nets. On one occasion Gladys Thompson describes how, on the track of two knitters who lived on

Holy Island, she hired a young lad to drive her across to the island from Berwick. He arrived in a car at least thirty years old and covered with

rust and sand. Their journey, made before the causeway linking the island to the mainland was built, entailed driving through the sea which

surged into the ancient car through the floor boards.

Many of the stitch motifs used to decorate the Ganseys were inspired by the everyday objects in the lives of fishing families. Some of the best-

known designs represent ropes, nets, anchors and herringbone. Other patterns are based on the weather, echoing the shapes made by waves,

hail or flashes of lighting. Some patterns had more complex symbolic meanings. One of the traditional Filey patterns, for example, is a zigzag

design called “marriage lines” which represents the ups and downs of married life.

It was even possible for fishing families to recognize from the pattern of a Gansey, which fishing village, or even which family, the wearer came

from. At a time when the loss of a boat was a frequent occurrence, deliberate mistakes or the wearer’s initials were often incorporated into the

design in order to help to identify a body recovered from the sea. As the Gansey was was traditionally worn tight-fitting and close to the skin,

and with no seams to come apart, it could not be washed off in the water.

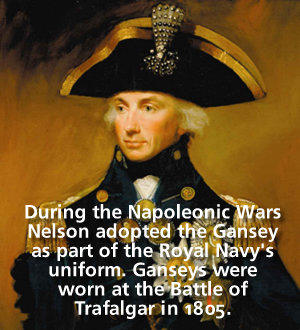

By tradition, the sweaters worn by all kinds of seafarers, whether they be fishermen, naval or retired sea salts, are navy blue—a colour reflecting

the sea and sky. Before the advent of synthetic dyes in the late nineteenth century, blue was obtained by using natural indigo, a plant extract

imported from India. However, summer weight Ganseys, knitted in a three- or four-ply yarn rather than the usual five-ply, were sometimes pale

grey or fawn. In a world which is becoming increasingly global in popular culture, the preservation of our traditional craft takes on a fresh

urgency.

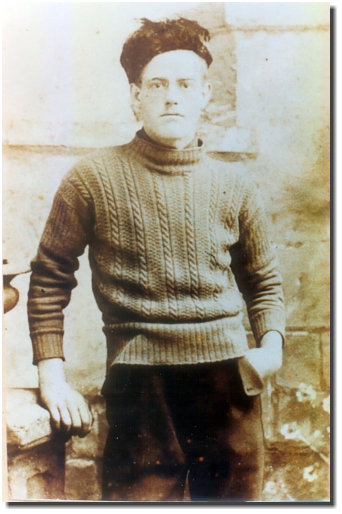

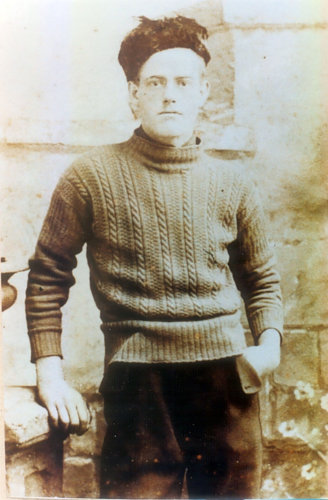

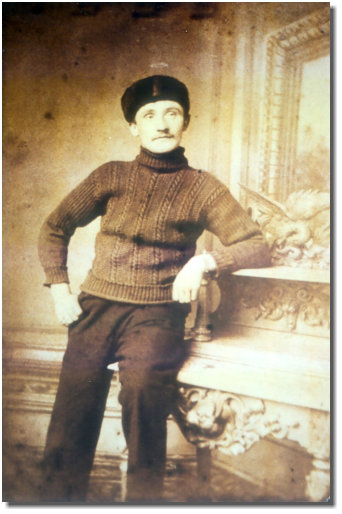

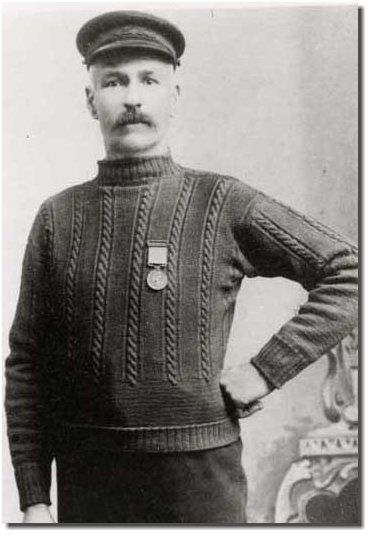

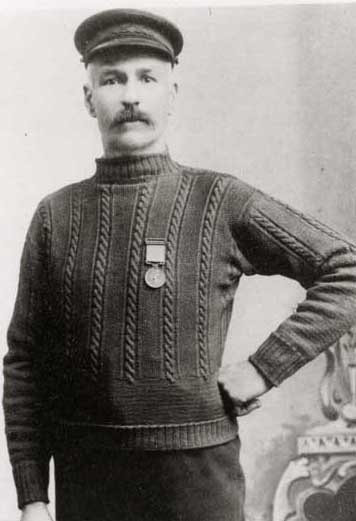

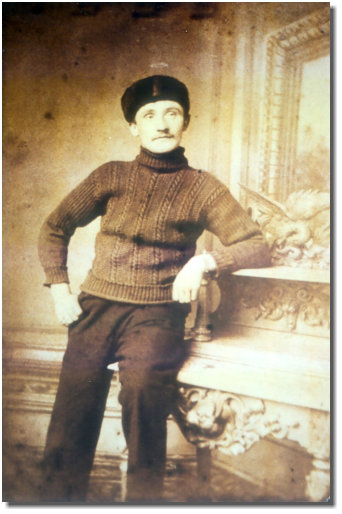

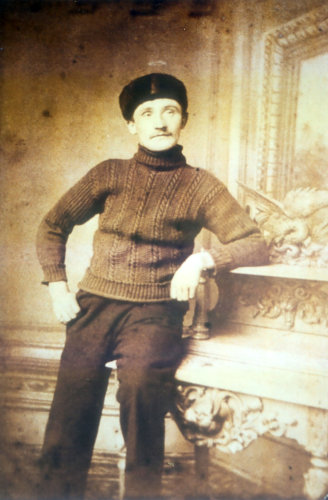

Two vintage

Ganseys:

Newbiggin (above) and Cullercoats Rocket Brigade (right, with the neck having been re-knitted)

Authentic hand-knitted Ganseys, Gansey Knitting Kits, striped cotton Breton shirts, traditional wool knitwear from Le Tricoteur (Guernseys) and Armor Lux of France

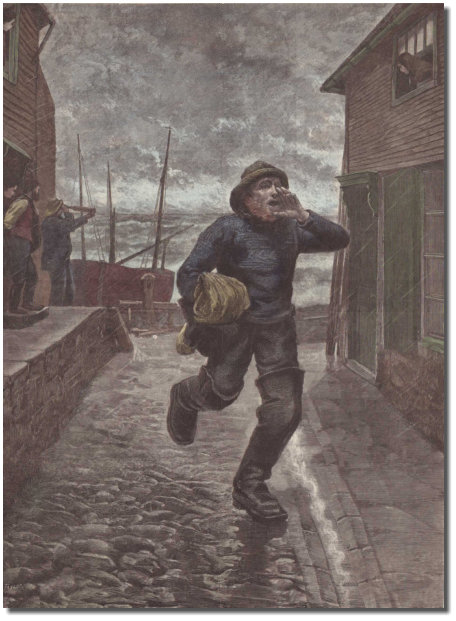

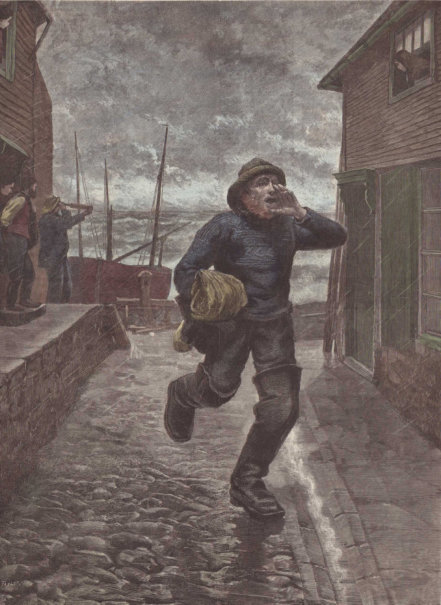

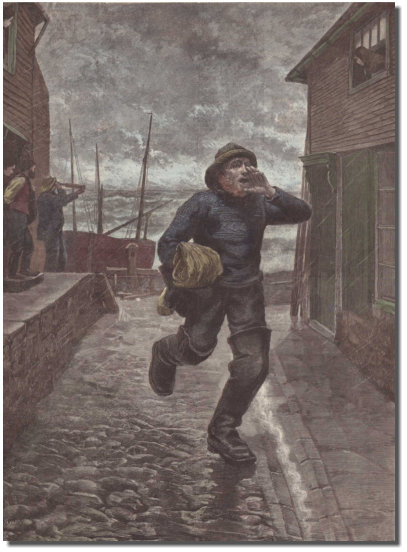

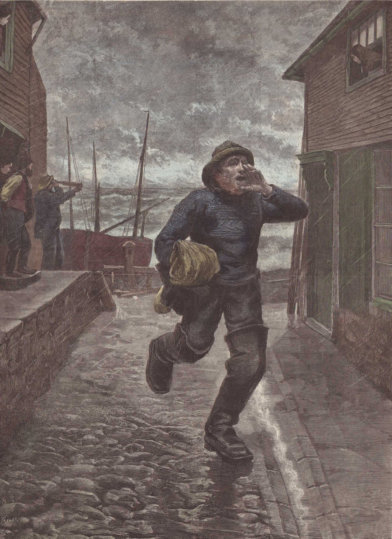

The print above left, showing a fisherman running through the streets of

a small northern fishing village shouting "All hands man the Life-Boat!" is

dated 26 November 1887. The fisherman is clearly wearing a Gansey

which, upon closer inspection, is almost certainly that of the Cullercoats

Rocket Brigade (an example of this pattern is shown below).

Over a century later, the same pattern can be knitted, and in the same

method, all-in-one piece, on five needles, in the finest quality 5-ply

worsted wool. If the fisherman returned today, he would find a few

things still familiar in Flamborough, and much that was alien. The fishing

boats (known locally as "cobles") would still be instantly recognizable, as

would Flamborough lighthouse and, if he walked into the premises of

Flamborough Marine, upon my soul, he would find a match for his own

Gansey.

A Unique Garment

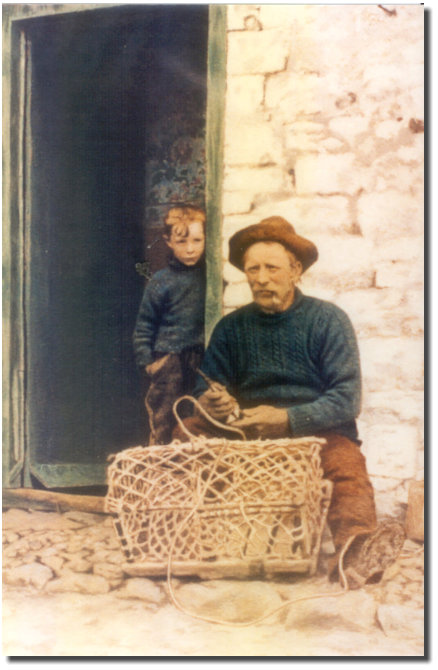

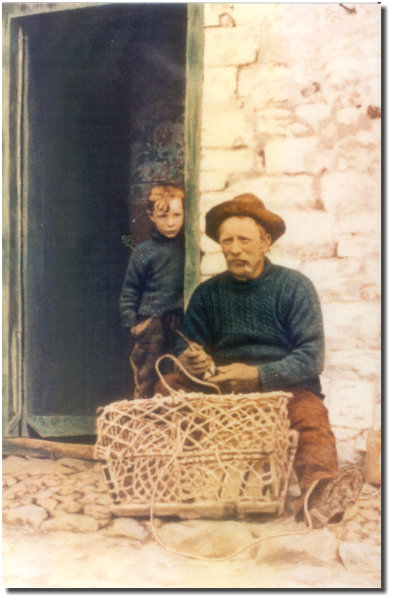

The photograph at left shows Jack Cross of Flamborough mending his pots. The photograph was taken shortly before Jack and his two eldest sons were drowned at North Landing, Flamborough on Friday 5 February 1909 while trying to land their catch in a gale. The photograph was kindly donated by the third son, the late Mr Edward Cross, who is the small boy standing in the cottage doorway behind his father. Old sepia photographs evoke the romance of far-off times. Yet there was little romantic in the life of a North Sea fisherman at the turn of the century when most days involved a struggle against the elements. Life could be just as hard for the womenfolk. Days were long but, in addition to such essential tasks as baiting the lines, time would be set aside for Gansey knitting, either for members of the immediate family or else for sale to raise a few extra shillings. Great pride was taken in this knitting, especially for the ‘Sunday best’ Gansey (often not in the traditional navy) to be worn at such occasions as the Flamborough sword-dancing or Filey fishermen’s choir, both of which still thrive today. At some time past the custom arose that each fishing community would have its own identifiable pattern based on a selection of motifs related to the sea: nets, ropes, ladders, herringbones, and so on. Although it is now impossible to ascertain precisely when the patterns came into being, this style of knitting originated during the reign of Elizabeth I and the patterns were fixed by the beginning of the nineteenth century. This means that it is possible to tell where a fisherman came from by the pattern on his Gansey; it is also the factor which, more than anything, makes the Gansey unique. Eventually, however, the craft of Gansey knitting went into steady decline as younger people moved out of the fishing villages and was in danger of dying out completely. Each Gansey is a living part of history and we believe it is essential that the craft is maintained and nourished. Every Gansey tells its own story. This was originally for a very practical, if morbid, reason. As each village fishing community could be identified by the design on its Gansey, if the body of a fisherman was found it could then be returned to his home for burial. In larger fishing communities, small alterations to the basic pattern could even allow for the differentiation of families within that village. Indeed, it is perhaps not too great an exaggeration to say that Ganseys helped foster the community spirit. Today that spirit is alive and well and Ganseys are still being worn, not only by those who work in them, but also by those who appreciate the workmanship, history, and beauty of these remarkable sweaters. Note that the patterning is the same, back and front. This means that the Gansey is reversible, so that areas which come in for heavier wear, such as the elbows, can be alternated. Traditional Ganseys are knitted in the round, apart from the chest and back, which are knitted back and forth on two needles before being joined at the shoulders. They are a snug fit; a baggy sweater would be a liability on a fishing boat. The fake “side seams,” usually just a row of purl stitches at the sides, serve to keep the knitter on track. They are where adjustments can be made in size, without compromising or interfering with the main pattern.

Web-site design & content Copyright © 2026 Geoffrey Miller

Victorian Fishermen

Flamborough

Head

Flamborough Marine

Your source for authentic

hand-knitted Ganseys, Gansey

Knitting Kits, plus a range of

quality, traditional knitwear

and Armor Lux pure cotton

Breton shirts

We pride ourselves on our personal

attention to detail. If you are at all

unsure about any aspect of our

products, telephone, write or e-mail

us with your query which will be

answered promptly and, we hope,

knowledgeably. We wish to ensure

that you are completely satisfied

before making a purchase, as well

as after.

This stunning Aran pattern shown

above (a one-off commission)

shows what our talented knitters

are capable of.

Rajiv Surendra wearing his specially-commissioned Gansey

At left: a classic

Whitby Gansey in Dark

Navy 5-ply worsted

wool

Flamborough Marine : The Manor House : Flamborough : Bridlington : East Riding of Yorkshire Telephone 01262 850943

If your browser indicates that this site is not secure, please click HERE to go to the secure version.

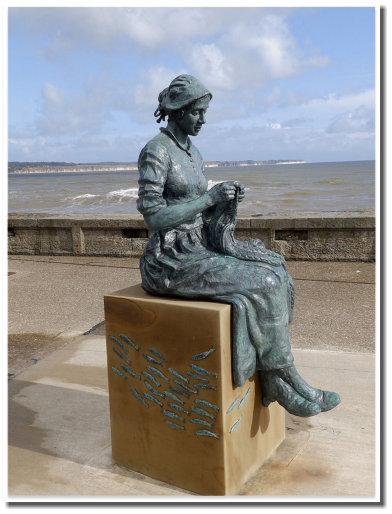

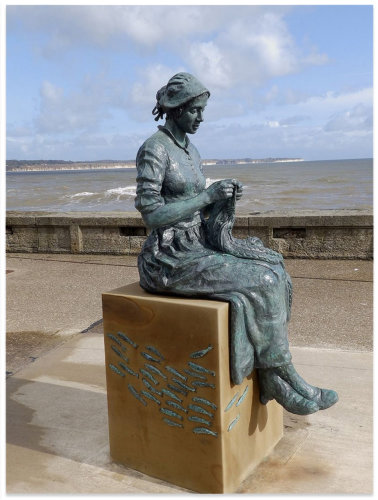

The Gansey Girl (below) immortalizes the tradition of Gansey knitting in

bronze. Situated on the harbour in Bridlington, with Flamborough Head in

the background, the statue, created by Steve Carvill (with some input from

my late wife, Lesley) depicts a fisherman’s wife knitting a Gansey.

Photographs kindly supplied by Kevin Groocock of H&K Bempton Crafts

The coble, Gansey Lass, under sail off Flamborough Head

We

recently

received

this

message

from

Eric

Taylor:

"11

years

ago

I

travelled

to

the

Antarctic

and

South

Georgia,

taking

with

me

the

Flamborough

pattern

Gansey

that

my

wife

had

knitted

for

me

from

a

kit

she

bought

from

you.

I

was

just

going

through

my

old

photos

and

found

this

one

of

me

by

Ernest

Shackleton’s

grave

at

Grytviken

on

South

Georgia

.

.

.

I

still

wear

my

Gansey

very

regularly

during

the

winter,

and

it’s

as

fantastic

now

as

it

was

when

I

was

first

given

it!"

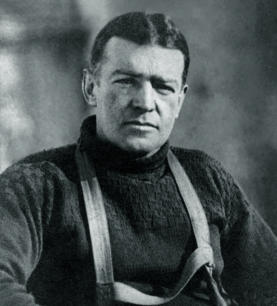

Also

shown

is

a

photograph

of

Ernest

Shackleton,

clearly

wearing

a

Gansey

(though

not

one of ours!).

Gansey Price List

Size (inches/cm)

38" chest

97cm

£500

40" chest

102cm

£510

42" chest

107cm

£520

44" chest

112cm

£530

46" chest

117cm

£540

48" chest

122cm

£550

50" chest

127cm

£570

Larger or smaller, please inquire

For U. S. orders, please add 10%

When Lesley Berry initially conceived the idea to try to revive the dying craft of

Gansey knitting in 1981, the first task was to recruit knitters of the requisite

standard, which proved easier said than done. However, the first knitter taken on

was to prove of exceptional ability starting a friendship which has lasted till the

present day. Marion Brocklehurst went on to produce a regular supply of Ganseys

over the next forty years, eventually totalling over five hundred, of all sizes and

patterns.

Marion also was our expert for Special Commissions and it was as a result of this,

after we had been approached by Rajiv Surendra in 2012, that she produced the

exquisite Gansey shown here. Marion went on to knit further Ganseys for Rajiv and

Rajiv, in turn, has produced an excellent video on Gansey Knitting which, in addition

to detailing the history, also pays tribute to Marion.

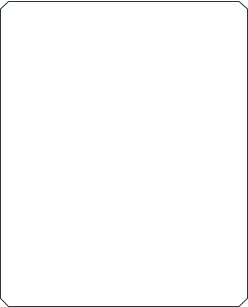

Marion’s last Gansey was yet another Rajiv “Special Commission” while her recent

Flamborough Gansey in the attractive “Helford Blue” colour wool is now proudly

being worn by the novelist Peter Benson, who kindly sent the photograph at right.

Details of Peter’s novels can be found here: Peter Benson

Our longest-serving Knitter

Rajiv Surendra’s excellent video

on the history of the Gansey

Contact Information

Flamborough Marine Limited

The Manor House

Flamborough

Bridlington

East Riding of Yorkshire

YO15 1PD

United Kingdom

Telephone:

01262 850943

International:

+44 1262 850943

E-mail:

gm@flamboroughmarine.co.uk

Few occupations

are more at the

mercy of the wind

and weather than

fishing. And it was

the practical

requirement for

warm yet

unencumbering

clothing that

prompted the

development of a

fascinating

tradition in

fishermen’s

sweaters, variously

known as jerseys,

Guernseys and

Ganseys.

It is likely that the word ‘jersey’, used to describe a knitted garment,

owes its derivation to the name of the largest of the Channel

Islands, where worsted spinning was once a staple industry. Over a

period of time, the close-fitting garments knitted in worsted-spun

yarn made in Jersey, and favoured by sailors and fishermen, became

known as jerseys.

Similarly, the neighbouring island of Guernsey gave its name to the

classic square-shaped wool sweater, which was designed with a

straight neck so that it could be reversed. Gansey, a term which

crops up in the writings of both Samuel Beckett and James Joyce, is a

dialect variation of Guernsey.

Until the coming of the machine age in the nineteenth century, most

industries were small-scale and craft-based. As early as 1589,

however, the invention of the knitting frame by William Lee, a

brilliant Nottinghamshire clergyman, had put into motion the

gradual migration of hosiery manufacturing from the domestic

setting to the factory. The uptake of machines was uneven, with

pockets of the knitting industry, such as the famous knitters of Dent

who made small items on short needles, resisting change for many

years.

The production of heavier gauge knitwear remained a largely

domestic activity until much more recently, with women knitting for

entire families well within living memory. Every village shop would

have boasted a section devoted to knitting yarn, and the market

towns would have had at least one thriving wool shop.

The isolated communities along the rugged British coastline were,

by necessity, even more self-sufficient than those further inland. In

the poor fishing communities, families could ill afford the luxury of

goods imported from the outside world. Women knitted for their

sweethearts, husbands and children. At a time when resources were

scarce, outgrown clothes were passed down and adults’ garments

cut down and remade for children.

Visitors to the Yorkshire fishing ports such as Whitby and Filey and

tiny villages such as Seahouses on the rugged Northumberland

coast, reported seeing women sitting in their doorways busy with

their needles. Never wasting a moment that could be used to earn

an extra penny, women worked late into the evening by the light of

rush lamps, knitting the navy-coloured yarn more by feel than by

eye.

Although the classic Guernsey sweater remained plain (some

Guernsey parishes did, however, have their own patterns), the stitch

patterns used became more complicated the further north the

garment spread, with the most complex evolving in the Scottish

fishing villages. These elaborate patterns came south with the

Scottish herring fleet, as the women folk followed their husbands

down the coast to gut the fish. Thus the pattern known as Whitby

flag is in fact an interpretation of a Scottish design.

Young women, who had received little formal education, would

develop the ability to memorize complicated patterns, which were

passed down from mother to daughter, gathering new variations

with each generation. The garments were made on five or more

needles, often called “wires” or “pins”, so as to be seamless. It was

not unusual for men, too, to knit ganseys. Knitting was a natural

extension of the familiar tasks of making and mending fishing nets,

routine jobs which required considerable dexterity.

Tightly knitted in worsted yarn the fisherman’s Gansey was virtually

wind-proof and water-proof. As these working garments were rarely

washed, there is no doubt that a layer of filth would have added to

the general protective effect. It is consoling to learn that fishermen

had “Sunday best” Ganseys which, being decidedly more fragrant,

were worn for church and on high days and holidays.

Many venerable Ganseys appear in the sepia toned photographs

taken by the well-known Whitby photographer Frank Meadow

Sutcliffe from 1880 to the turn of the nineteenth century. Prints

made from Sutcliffe’s original glass plates provide a fascinating

insight into the clothing of ordinary working people.

The characteristic, almost tubular, shape of the fisherman’s Gansey

was dictated by practicality. The welt, neck and cuffs were knitted

tight so as to keep out winter blasts. According to hearsay, so tight

were the Ganseys knitted for the unfortunate children of one

fisherman that, when the garments were pulled over their heads,

the children’s ear lobes bled.

The cuffs, also made to be close-fitting, generally ended short of the

wrist to avoid impeding the hands and becoming soaked with sea

water as the men worked. The close fitting design also helped to

reduce the chances of the hem or cuffs becoming caught on pieces

of equipment or tackle, a mishap which could prove fatal

As time took its toll on the cuffs and elbows, the lower half of the

sleeves could be unravelled and re-knitted with new yarn. Garments

made in various shades of blue, ranging from deep navy to a hue

faded with age, were a common sight.

The upper part of the body was knitted more densely than the lower

part to provide extra warmth, and it was on the yoke and upper

arms that the knitters had the opportunity to show off their knitting

skills and to elaborate on the basic stocking stitch with numerous

variations.

For detailed records of the many local interpretations of traditional

fishermen’s jerseys, we are indebted to the tireless efforts of Gladys

Thompson, who, in the 1950s, pencil and paper in hand, scoured the

fishing ports on the east coast—from Sheringham and Cromer in

Norfolk as far as Upper Largo in Fife.

Her quest, fired by a determination to preserve for future

generations patterns which were seldom written down, took her

down the narrow harbour ginnels (passages) and into the cramped

fishermen’s cottages, where often a single room served as kitchen,

bedroom and living room, with an attic above for storing and

mending nets.

On one occasion Gladys Thompson describes how, on the track of

two knitters who lived on Holy Island, she hired a young lad to drive

her across to the island from Berwick. He arrived in a car at least

thirty years old and covered with rust and sand. Their journey, made

before the causeway linking the island to the mainland was built,

entailed driving through the sea which surged into the ancient car

through the floor boards.

Many of the stitch motifs used to decorate the Ganseys were

inspired by the everyday objects in the lives of fishing families. Some

of the best-known designs represent ropes, nets, anchors and

herringbone. Other patterns are based on the weather, echoing the

shapes made by waves, hail or flashes of lighting. Some patterns

had more complex symbolic meanings. One of the traditional Filey

patterns, for example, is a zigzag design called “marriage lines”

which represents the ups and downs of married life.

It was even possible for fishing families to recognize from the

pattern of a Gansey, which fishing village, or even which family, the

wearer came from. At a time when the loss of a boat was a frequent

occurrence, deliberate mistakes or the wearer’s initials were often

incorporated into the design in order to help to identify a body

recovered from the sea. As the Gansey was was traditionally worn

tight-fitting and close to the skin, and with no seams to come apart,

it could not be washed off in the water.

By tradition, the sweaters worn by all kinds of seafarers, whether

they be fishermen, naval or retired sea salts, are navy blue—a colour

reflecting the sea and sky. Before the advent of synthetic dyes in the

late nineteenth century, blue was obtained by using natural indigo, a

plant extract imported from India. However, summer weight

Ganseys, knitted in a three- or four-ply yarn rather than the usual

five-ply, were sometimes pale grey or fawn.

In a world which is becoming increasingly global in popular culture,

the preservation of our traditional craft takes on a fresh urgency.

A Vintage Gansey

The print above, showing a fisherman running through the streets

of a small northern fishing village shouting "All hands man the Life-

Boat!" is dated 26 November 1887. The fisherman is clearly

wearing a Gansey which, upon closer inspection, is almost certainly

that of the Cullercoats Rocket Brigade.

Over a century later, the same pattern can be knitted, and in the

same method, all-in-one piece, on five needles, in the finest quality

5-ply worsted wool. If the fisherman returned today, he would find

a few things still familiar in Flamborough, and much that was alien.

The fishing boats (known locally as "cobles") would still be instantly

recognizable, as would Flamborough lighthouse and, if he walked

into the premises of Flamborough Marine, upon my soul, he would

find a match for his own Gansey.

A Unique Garment

The photograph at left shows Jack Cross of Flamborough mending his pots. The photograph was taken shortly before Jack and his two eldest sons were drowned at North Landing, Flamborough on Friday 5 February 1909 while trying to land their catch in a gale. The photograph was kindly donated by the third son, the late Mr Edward Cross, who is the small boy standing in the cottage doorway behind his father. Old sepia photographs evoke the romance of far-off times. Yet there was little romantic in the life of a North Sea fisherman at the turn of the century when most days involved a struggle against the elements. Life could be just as hard for the womenfolk. Days were long but, in addition to such essential tasks as baiting the lines, time would be set aside for Gansey knitting, either for members of the immediate family or else for sale to raise a few extra shillings. Great pride was taken in this knitting, especially for the ‘Sunday best’ Gansey (often not in the traditional navy) to be worn at such occasions as the Flamborough sword-dancing or Filey fishermen’s choir, both of which still thrive today. At some time past the custom arose that each fishing community would have its own identifiable pattern based on a selection of motifs related to the sea: nets, ropes, ladders, herringbones, and so on. Although it is now impossible to ascertain precisely when the patterns came into being, this style of knitting originated during the reign of Elizabeth I and the patterns were fixed by the beginning of the nineteenth century. This means that it is possible to tell where a fisherman came from by the pattern on his Gansey; it is also the factor which, more than anything, makes the Gansey unique. Eventually, however, the craft of Gansey knitting went into steady decline as younger people moved out of the fishing villages and was in danger of dying out completely. Each Gansey is a living part of history and we believe it is essential that the craft is maintained and nourished. Every Gansey tells its own story. This was originally for a very practical, if morbid, reason. As each village fishing community could be identified by the design on its Gansey, if the body of a fisherman was found it could then be returned to his home for burial. In larger fishing communities, small alterations to the basic pattern could even allow for the differentiation of families within that village. Indeed, it is perhaps not too great an exaggeration to say that Ganseys helped foster the community spirit. Today that spirit is alive and well and Ganseys are still being worn, not only by those who work in them, but also by those who appreciate the workmanship, history, and beauty of these remarkable sweaters. Note that the patterning is the same, back and front. This means that the Gansey is reversible, so that areas which come in for heavier wear, such as the elbows, can be alternated. Traditional ganseys are knitted in the round, apart from the chest and back, which are knitted back and forth on two needles before being joined at the shoulders. They are a snug fit; a baggy sweater would be a liability on a fishing boat. The fake “side seams,” usually just a row of purl stitches at the sides, serve to keep the knitter on track. They are where adjustments can be made in size, without compromising or interfering with the main pattern.

Flamborough Marine

Your source for authentic

hand-knitted Ganseys, Gansey

Knitting Kits, plus a range of

quality, traditional knitwear

and Armor Lux pure cotton

Breton shirts

We pride ourselves on our personal

attention to detail. If you are at all

unsure about any aspect of our

products, telephone, write or e-mail

us with your query which will be

answered promptly and, we hope,

knowledgeably. We wish to ensure

that you are completely satisfied

before making a purchase, as well

as after.

This is the mobile variant of our web-site, specially designed for

viewing on smartphones, but lacking some of the more

detailed information available on our full-size site.

Flamborough Marine

The Manor House

Flamborough

Bridlington

East Riding of Yorkshire

Telephone 01262 850943