|

|

|

|

|

|

SUPERIOR FORCE

: The Conspiracy Behind the Escape of

Goeben and Breslau

© Geoffrey Miller |

|

|

|

|

|

Chapter 2

|

|

Opening Moves

|

|

|

Admiral Sir Archibald Berkeley Milne |

On 27 July

the Admiralty telegraphed to Milne that war was be no means impossible and he

should be prepared to shadow hostile men of war. It was emphasized that this was

NOT the Warning Telegram and Milne was directed to return to Malta, at ordinary

speed, and remain there while completing with coal and stores. |

|

Troubridge, at the

time still at Durazzo in Defence, was to be

warned to be ready to rejoin the force with dispatch.[1]

In accordance with the programme of his cruise, Milne was then at Alexandria in

Inflexible, together with

Indefatigable, the

armoured cruisers Warrior and

Black Prince, the light cruisers

Chatham,

Weymouth, Dublin and Gloucester, and 13

destroyers. With Defence at Durazzo, Milne’s

fourth heavy cruiser, Duke of Edinburgh, was at

Malta having just completed an annual refit[2]

while his third battle cruiser, Indomitable,

which was four months overdue for a refit, had parted company from the Squadron

off Beirut on 21 July to return to Malta ahead of the squadron for the refit to

begin. Her Captain, Francis Kennedy, had been complaining to Milne since March

1913 regarding the state of the electrical wiring in particular and the ship was

placed in dockyard hands immediately upon her arrival on 23 July. By the time

Milne received the preparatory telegram Indomitable had already had a great deal of machinery removed, but

the refit was quickly forgotten and work commenced at once to prepare the ship,

replenish the magazines and fill the empty bunkers with 1,800 tons of coal.[3]

With the attitude of Italy still

uncertain, with Goeben known to be

then at Pola, and aware also that Milne was under strength by one battle cruiser

(Invincible), Churchill asked

Battenberg on 28 July to consider whether or not the battle cruiser

New

Zealand should be sent out to join the squadron;[4]

however, it was decided at an Admiralty conference that afternoon

not

to reinforce Milne.[5]

As the Admiralty pondered thus, Milne’s squadron left Alexandria, having

insouciantly, if punctiliously, waited there for over 12 hours so as to be able

to depart at the time published in the programme. Even then there seemed no

particular urgency and this relaxed attitude was reinforced by an erroneous W/T

message received via Dublin at Port

Said to the effect that Serbia had accepted the Austrian demands and there would

be no war. The larger ships calmly practised range-keeping in the forenoon and

only after that were they ordered to raise steam for extra speed.[6]

Such repose was no longer evident in London. On 29 July the Cabinet considered

its position in case Belgian neutrality should be violated and decided that, in

this eventuality, the British response would be determined by policy rather than

legal obligations. Grey was authorized to inform the French and German

Ambassadors ‘that at this stage we were unable to pledge ourselves in advance,

either under all conditions to stand aside, or in any condition to join in.’

Churchill then described the naval precautions that had been taken and it was

resolved that the ‘preliminary stage’ had arrived and the ‘warning

telegram’ should be sent. This was done shortly before 2 p.m., immediately

after the Cabinet rose;[7]

meanwhile Milne’s squadron had arrived at Malta during the day. That evening

the official warning telegram was in the C-in-C’s hands at a minute after 10

o’clock — in the event of war, Milne’s

War Orders No. 2 would come into force.[8]

The following afternoon, in his room

at the Admiralty, Churchill sat down to draft a telegram to Milne which would

set in motion the train of events leading to Troubridge’s fateful course of

action and which would gain notoriety as the “superior force” telegram. As

such, it is essential to study Churchill’s original draft to discover the

changes he made and to try to ascertain the reasons for those changes. In the

following, the words struck through were deleted in the final version, and the

words in square brackets were added. Churchill wrote, initially:

Shd

war break out and England and France engage in it, it now seems probable that

Italy will remain neutral and that Greece can be made an ally. Spain also will

be friendly & possibly an ally. The attitude of Italy is however uncertain

and it is especially important that your squadron shd not be seriously engaged

with Austrian ships before we know what Italy will do. Your first task shd be to

aid the French in the transportation of their African army by covering and if

possible bringing to action fast German or Austrian ships [particularly Goeben] wh may interfere with that transportation. You will be

notified by telegraph when you may consult with the French Admiral. Do not [at

this stage] be brought to action against superior forces in any w except

[in combination with the French] as part of a general battle. The speed of your

squadrons is sufficient to enable you to choose your moment. We shall hope to

reinforce the Mediterranean and you must husband your forces at the outset.

W.S.C. 30.7[9]

With

the first draft, Churchill’s intentions become somewhat clearer than a reading

of the final telegram as sent would indicate, and it is a pity he did not take

the time to compose a fresh draft instead of tinkering with the first. This

might possibly have avoided the awkward construction of the central sentence: as

Churchill removed the reference to Austrian ships, to avoid contradicting the

preceding sentence (which warned Milne not to become “seriously engaged”

with Austrian ships until the attitude of Italy was clarified), the following

sentence now referred only to Goeben and

Breslau and

should have said as much. All of Churchill’s subsequent alterations occur in

the sixth sentence. As originally drafted it read: ‘Do not be brought to

action against superior forces in any w[ay?] except as part of a general

battle.’ As it stood, this was hopelessly ambiguous, failing to define what

constituted either “superior forces” or “a general battle”. The addition

of the qualifying clause “in combination with the French” after “except”

tends to indicate what Churchill later admitted he had clearly meant: do not

engage the Austrians single-handed.[10]

However, the weight of the additional clause fell on the first half of the

sentence, leading to the possible interpretation that “superior forces”,

whatever they might be, could be engaged with French assistance. The sentence,

as Churchill meant it, was, in any case, superfluous: Milne had already been

warned off the Austrians. Had Churchill simply deleted the sentence, instead of

altering it in three instances, Troubridge’s torment on the night of 6/7

August could have been avoided. The outcome might not have changed – as

Souchon could still have declined battle if he chose – but Troubridge’s

reputation would have remained intact.

The perils of letting loose a

headstrong politician in the Admiralty were also illustrated by the confusing

advice regarding Italy: first, it ‘now seems probable’ that she would remain

neutral but then, in the following sentence, the attitude of Italy was

‘uncertain’. Similarly, why did Churchill assure Milne that ‘we shall hope

to reinforce the Mediterranean’ when he knew that Battenberg had already

decided against such a move? There remains also the possibility that Churchill

was influenced in drafting the telegram by the presence of Admiral Fisher at the

Admiralty that day: whether Fisher had a hand in its composition or whether

Churchill sought to impress his mentor is problematical. What is certain is that

Fisher admitted to having had ‘a very exciting time’ with Churchill on the

30th and that, unusually for him, he ‘did not get back till late & did not

sleep a wink last night in consequence! I can’t leave here while war is

likely’, he blissfully declared, ‘as apparently I am wanted…’[11]

Milne

replied to the Admiralty that, in order to carry out his primary duty of

assisting the French to protect their transports, and in view of the greater

strength of the Austrian and Italian fleets, he would keep his force

concentrated at Malta until he received permission to consult the French

Admiral. This meant that he could not afford to spare cruisers to protect trade

in the Eastern Mediterranean basin but he would detach a single cruiser to watch

the southern entrance of the Straits of Messina. The contingency that Italy

would side with the Triple Alliance had to be allowed for but already, by the

last day of July, the rumour had spread throughout the ships gathered in Malta

that Italy would not participate. ‘This came as a surprise to nobody’, wrote

one of the Defence’s midshipmen,

‘and it is assumed she will chip in on the winning side a little later on.’[12]

His only other worry concerned the whereabouts of the German cruiser

Strassburg

– last reported in the Azores – and possibly heading for the Mediterranean.[13]

The Director of the Operations Division, Rear-Admiral Leveson, minuted that

Milne appeared ‘to be carrying out the spirit of his orders and no reply seems

required other than informing him that Strasbourg is in the English Channel.’ Battenberg approved.[14]

Milne lost the services of one of

his cruisers, temporarily, when Black Prince departed at 7 a.m. on Saturday, 1 August to collect

Kitchener and his staff from Marseilles with instructions to convey them to

Alexandria; however, the order was cancelled the following day when it was

decided that Kitchener should remain in London as a member of the Cabinet.[15]

Late that Saturday night the first tenuous clues as to the movements of the

German ships were received in London when it was reported (erroneously) from

Rome that Breslau was coaling in

Brindisi, but that it was thought she would be returning to Albania. This

information was updated some hours later when the Admiral Superintendent at

Malta, reported (again incorrectly) that both Goeben and

Breslau were

coaling in Brindisi.[16]

Meanwhile, Troubridge’s ship buzzed with activity in preparation for war:

All

loose gear was bundled out of the ship into empty coal lighters. Officers and

all hoisting the stuff out. It was quite heavy work lumping the sea chests about

the place. There was not time to stow the lighters at all carefully so

everything was just jumbled on pell mell…[17]

The feverish activity in Malta was

mirrored in London on Sunday 2 August. The attitude of Italy had now become

clearer and it seemed increasingly likely that she would adopt a course of

neutrality: in this eventuality Churchill instructed that Battenberg and the new

C.O.S., Vice-Admiral Sir Frederick Doveton Sturdee, should consider whether the

four ships of Troubridge’s First Cruiser Squadron and one battle cruiser or,

alternatively, two heavy cruisers and two battle cruisers, should not return

home. ‘The French should be consulted about this, and as to their plans’,

the First Lord added, continuing: ‘You may do this as a piece of staff work

— making it clear that we cannot decide questions of policy.’[18]

So much for Churchill’s earlier promise to Milne that the Mediterranean would

be reinforced.

Battenberg, clear in his own mind at

least as to the direction that Admiralty policy had taken during his tenure,

first stated the position simply: ‘England massed in the North,

safeguarding French interest against Germany. France massed in Meditn.,

safeguarding British interests against Austria.’ The First Sea Lord

immediately had second thoughts with regard to the French task and replaced

“British interests” with the more politic “joint interests”;

interestingly, the corresponding change was not made to the unselfish British

task, which seemed to be solely concerned with protecting the French. Battenberg

concluded that France was overwhelmingly superior to Austria in battleships,

armoured cruisers and torpedo craft, but quite deficient in light cruisers. And

as, in any case, Goeben and

Breslau

had to be covered by the British, Battenberg proposed that

Indefatigable

(the newest of the three British battle cruisers) and Dublin should remain on station to tackle

Goeben and

Breslau and

that the light cruisers should remain to assist the French but that the

remainder – two battle cruisers and the First Cruiser Squadron – should

return to the North Sea.[19]

Sturdee, as his name almost seemed to imply, was far more cautious — and

realistic. ‘I rather hold that an open mind be kept on making any

reduction’, he informed the First Sea Lord, adding,

The

situation will have to be very clear before doing so. Even against Austria and

the Goeben. If French and English squadrons do not work well in

combination the reduction could not be made. In any case I should prefer leaving

for a time First Cruiser Squadron with the Inflexibles on the station. First

Cruiser Squadron might prove a valuable asset for our trade either in

Mediterranean or from Gibraltar.[20]

Was

Battenberg seriously of the opinion that a single battle cruiser and light

cruiser could guarantee the destruction of Goeben and

Breslau, or was

it simply a case of his writing what he thought the First Lord wanted to hear?

In any event, Sturdee’s wiser counsel prevailed and at 1.30 on the afternoon

of Sunday, 2 August, Battenberg drafted a signal to Milne (no. 196) ordering

that: ‘Goeben must be shadowed by

two battle-cruisers. Approaches to Adriatic must be watched by cruisers and

destroyers. Remain near Malta yourself.’ To this, Churchill added: ‘It is

believed that Italy will remain neutral. You cannot yet count absolutely on

this.’[21]

In Malta, one of Milne’s first

duties that morning had been to interview Captain Kennedy of

Indomitable

who had been off duty, ill, for a week. Kennedy assured Milne he was fit to put

to sea, then returned to Indomitable

to address the ship’s company on the subject of being prepared for action both

morally and physically.[22]

At 11.50 a.m. leave was granted throughout the squadron (until 10 p.m. for men

and midnight for officers); however, this proved short-lived in the case of

Indefatigable,

Indomitable, Defence, Warrior and the 1st and 2nd Division destroyers as,

just after 2 p.m., a recall signal was made and the order given to raise steam

immediately for full speed.[23]

Meanwhile, Troubridge had been shown a copy of Churchill’s “superior

force” telegram by Milne at 9 a.m. after breakfasting with the C-in-C

following which Milne left Troubridge for half an hour so that he [Troubridge]

could study the situation while Milne was engaged with his secretary on other

business.[24]

Although both officers later agreed

that a conversation then ensued as to the definition of superior force there was

to be also a further crucial misunderstanding as to whether the two battle

cruisers were to be attached permanently to Troubridge’s flag or only

temporarily, for the purpose of shadowing Goeben. Troubridge also subsequently maintained that his views as to

the relative merits of the armoured cruiser type (none of which had been laid

down since the Minotaur class early in

1905, which included Defence,

now his

own flagship) were well known, as was his opinion that a single battle cruiser

was a superior force to a whole

cruiser

squadron ‘on a day of perfect visibility.’ There is some evidence that

Churchill himself shared Troubridge’s misgivings on this subject — at least

in so far as the smaller cruisers were concerned. In March 1913 Fisher, in his

customary language, referred to Churchill’s argument ‘about the small

cruisers who will all be gobbled up by “Goebens” like the Armadillo gobbles

up ants and the bigger the ant the more placid the digestive smile’;[25]

naturally, in the face of prospective battle in 1914, this sentiment was soon

forgotten.

Troubridge had been asked by Milne

in October 1913 to lecture the officers of the fleet, aboard

Inflexible,

on the relative merits of these types of ships; he had also been involved in the

1913 manoeuvres where he first saw battle cruisers in action. In these

manoeuvres, Troubridge’s heavy cruisers chanced upon the new battle cruiser

Lion

from the opposing fleet. As Lion

appeared to be ‘almost out of sight’ Troubridge never dreamt of opening fire

yet, he later complained, ‘in a moment half of my squadron were adjudged by

the Chief Umpire to be out of action to her fire.’[26]

The Admiralty’s own report on the principal cruiser work carried out in 1913

tended to support Troubridge with one possible, yet crucial, exception. Although

the report’s author, Vice-Admiral Sturdee, maintained that the exercises had

clearly shown that armoured cruisers ‘have been disclassed [sic]

by the introduction of the fast and powerful battle cruisers’, he did enter

one important caveat: ‘Still, the armoured cruisers possess a good armament,

but insufficient speed…In combination, the later classes might hold their own

against one battle cruiser, but when spread beyond concentrating distance they

will fall an easy prey to an enemy’s battle cruiser. From the experience

gained during these exercises armoured cruisers should not be unduly separated,

but they should work in squadrons when they may execute most valuable work as

cruisers...’[27]

The report might almost have been written with Troubridge’s later predicament

in mind; however, although it had been completed by July 1914 and 16 copies had

been dispatched to Malta, they did not arrive till 8 August, two days too late

to have any effect on Troubridge’s actions.[28]

On the question of what constituted

superior force, Troubridge later recalled his conversation with Milne that humid

Sunday afternoon after the receipt of Battenberg’s telegram: ‘I hope, Sir,

that this is left to my judgement’, adding, ‘You know, Sir, that I consider

a battle-cruiser a superior force to a cruiser squadron, unless they can get

within range of her.’ In this version Milne allegedly replied that the

situation would not arise, as Troubridge would have the two battle cruisers with

him.[29]

For his part, Milne remembered that Troubridge did speak of the difficulty his

armoured

cruisers might encounter in engaging

Goeben

but that they agreed that it would be possible to fight a successful action if

Goeben

could be caught unawares, or in a situation where manoeuvring would be difficult

for the German ship. Milne, however, was adamant that Troubridge ‘did not leave

me with the impression that he would not engage, although he said it would be

difficult’,[30]

while, with regard to the question of superior force, Milne was equally

convinced that this part of his orders applied only to the Austrian fleet alone

and not to the German squadron.[31]

When Battenberg’s telegram no. 196

arrived that afternoon, Milne thereupon framed his Sailing Orders to Troubridge.

According to these, Chatham was to depart as soon as possible to watch the Straits of

Messina (she would leave at 5.12 p.m.), while Defence, Indomitable, Indefatigable, Warrior, Duke of Edinburgh,

Gloucester and the 1st and 2nd Division of Destroyers would carry out the

orders contained in Battenberg’s signal: during the night the destroyers would

push forward to watch the entrance to the Adriatic, during the day they would

retire to the Greek coast to save coal and rest the crews while the four

cruisers took over; the two battle cruisers were to remain in the rear to lend

support though, if Goeben were

sighted, she was to be shadowed by the two battle cruisers and a light cruiser.

Milne also passed on the latest – dubious – information, that

Goeben

and Breslau had apparently coaled at Brindisi on the 1st, and that it

had been reported that Breslau had

left to return to Albania.[32]

Although not in the sailing orders, Milne had received two further pieces of

information that afternoon: the consul at Brindisi wired that

Goeben

had now been sighted off Taranto[33]

and the Greek Government had reported that the Austrian Ambassador at

Constantinople had been inquiring as to the quantity of coal at Salonica which,

it was believed, might be required for an Austrian Squadron trying to intercept

Serbian stores at that port.[34]

Troubridge’s sailing orders also

contained the following admonition from Milne: ‘The Admiralty have informed me

that, should we become engaged in war, it will be important at first to husband

the naval force in the Mediterranean and, in the earlier stages, I [Milne] am to

avoid being brought to action against superior force. You are to be guided by

this should war be declared.’ This was Troubridge’s last opportunity to

clear up any lingering doubt about the question of superior force; he did not

take it.

By

attaching the two battle cruisers to Troubridge, Milne was acting in accordance

with Admiralty telegram no. 196 – which instructed that

Goeben

should be shadowed by two battle cruisers – and this was stated in his sailing

orders to Troubridge. As far as Milne was concerned, the detachment was a

temporary measure to shadow, and possibly deal with, Goeben,

however, his primary duty still remained the protection of the French transports

and the watch on the Adriatic. As ordered, Milne would remain near Malta in

Inflexible

co-ordinating his forces but, he maintained, it should have been obvious to

Troubridge that the Admiralty did not intend him (Milne) ‘to remain alone with

my flagship during the War.’[35]

Troubridge later implied that he had not been shown Admiralty telegram no. 196,

but only his sailing orders — the tenuous importance of this alleged omission

supposedly being that, whereas Battenberg’s telegram suggested that the

main

reason for the dispatch of the two battle cruisers was to shadow

Goeben,

Milne’s sailing orders to Troubridge appeared to downgrade this to an

ancillary function by merely instructing Troubridge that ‘Should the

Goeben be sighted you are to cause her to be shadowed by the two

battle cruisers.’ This was a distinction fine enough to be invisible.

Recalling his time at the Admiralty

as C.O.S., when he had been involved in the Anglo-French naval talks, Troubridge

knew that the French C-in-C would assume supreme command in the Mediterranean,

placing Milne who – as a result of Fisher’s legacy – was senior to Lapeyrère,

in an impossible position. Therefore, Troubridge assumed, the Admiralty would

have no option but to order Milne, in Inflexible,

to return to England while placing the remainder of the Squadron under

Troubridge’s permanent operational control, subject to the overall supervision

of the French C-in-C. Troubridge further maintained that, reinforcing this

impression, was his mistaken belief that the sailing orders Milne had shown him

originated from the Admiralty, rather than being Milne’s interpretation of

Admiralty orders.

Was Troubridge aware of Admiralty

telegram no. 196 or not? At first, he testified that Milne had shown him ‘what

I thought was an Admiralty telegram [referring to the sailing orders], but I now

find it was not’. He repeated this shortly afterwards: ‘he [Milne] pulled

out of his drawer what I though was a telegram from the Admiralty, but I see now

it was not’.[36]

But later still, at his Court Martial, Troubridge declared that, ‘My sailing

orders are before the Court. I was to take under my command a certain

force…and I was to carry out the orders contained in an Admiralty telegram

attached’.[37]

This last admission was forced out of Troubridge as the sailing orders he was

given by Milne clearly refer to the instructions received in Admiralty telegram

no. 196, ‘of which a copy is attached’.[38]

There can be no doubt then that, despite the earlier orders to the C-in-C,[39]

Troubridge was aware that for the time being Milne had not been ordered back to

England and, from this, it follows he should have realized that, as Milne was to

remain in the Mediterranean, the detachment of the battle cruisers to his flag

was temporary.

Troubridge took his misconception

with him and returned to his ship. As Defence would soon be ready to depart, he flashed a signal to Milne

at 4.52 p.m. to inquire whether he should wait for the battle cruisers. Milne

agreed that Defence should delay her

departure but that the destroyers should be dispatched immediately at 10 or 11

knots to save coal, with the remainder of the squadron catching them up later.[40]

At 5.45 p.m. Troubridge signalled the other captains of the ships assigned to

him and beckoned them to a meeting where he outlined the orders he had just been

given and ended by emphasizing that if Goeben and

Breslau were

sighted, even though war had not been declared, they were to be shadowed very

carefully. When he asked if there were any questions, Captain Kennedy of

Indomitable

sardonically inquired, ‘How is it proposed that 22 to 24 knot ships shall

shadow 27 to 28 knot ships that don’t want to be shadowed?’ Kennedy

subsequently recounted that his brother captains scoffed at such a question,

while Troubridge answered for them by saying it was common knowledge ‘that

Goeben

was drawing a foot and a half over her proper draught and so could not nearly

steam the speed she was supposed.’[41]

At least on this point Troubridge and Milne agreed: Milne had been informed by

the Harbour Master at Alexandria that when Goeben had visited the port in 1913 she had only one foot to spare

under her bottom. ‘It was generally known or rumoured’, Milne later

recalled, ‘that she drew more than she was intended to draw.’[42]

Kennedy remained unconvinced.

At 6.07 p.m. Troubridge informed the

ships under his command that he would organize them in two divisions, the first

comprising Defence, Warrior

and Duke

of Edinburgh, the second Indomitable

and Indefatigable, with the two light

cruisers Chatham and

Gloucester

acting separately.[43]

Finally, at 9.15 p.m. on 2 August, the ships slipped and proceeded from harbour

on course N.58º E. at 15 knots until they had caught up with the destroyers

which had left an hour earlier; then the fleet slowed to the cruising speed of

the destroyers, 10 knots.[44]

That first night the squadron went to ‘night defence stations’, the guns

being loaded with common shell.[45]

Milne informed the Admiralty of his

dispositions but – in the first intimation the Admiralty would receive of the

confusion caused by Churchill’s ‘superior force’ telegram – Milne wanted

to know whether, if Goeben and

Breslau

emerged from the Adriatic, he should concentrate all Troubridge’s forces

against them, or just the battle cruisers, leaving the remainder of the squadron

to continue watching the entrance to the Adriatic. This confusion was echoed in

London and was a direct result of both Churchill and Battenberg drafting

ambiguous orders. Battenberg’s annotation on Milne’s telegram stated

‘Watch on mouth of Adriatic should be maintained as well as shadowing

Goeben’[46]

giving equal preference to both objectives, however Churchill’s telegram to

Milne later that night read: ‘Watch on mouth of Adriatic should be maintained,

but Goeben is your objective. Follow

her and shadow her wherever she goes and be ready to act on declaration of war

which appears probable and imminent.’[47]

Churchill had thus altered the emphasis.[48]

Milne was also authorized that

evening to enter into communication with Admiral Lapeyrère. Four days earlier,

on the afternoon of 30 July, the French Naval Attaché, the Comte de

Saint-Seine, had seen Churchill and Battenberg at the Admiralty to suggest that

it was time for the joint signal books, held in readiness in sealed packets by

the French and British Cs-in-C, to be distributed amongst the individual ships

of the fleets. In view of his past exertions to maintain ‘freedom of choice’

Churchill remained hesitant and was able to stall the Attaché by arguing that

it was a matter for the two Cabinets and not the two Admiralties: ‘such action

was premature’, Churchill declared to Sir Edward Grey when notifying him of

Saint Seine’s approach, as ‘our strength and preparedness enable us to

wait.’[49]

While

strength and preparedness were on Britain’s side, morality was not — at

least as far as the French were concerned. All the glorious talk of ‘freedom

of action’ would shortly be replaced by accusations as the French Ambassador,

Paul Cambon, was made aware that he could not automatically count on British

support: in the coming struggle his main weapon would be a humble piece of paper

— the November 1912 letter from Grey.[50]

But it was not the only weapon in his armoury. On the afternoon of Friday 31

July Grey had had a ‘rather painful’ interview with Cambon at which, in

Asquith’s words, he ‘had of course to tell Cambon (for we are under no

obligation) that we could give no pledges, and that our action must depend upon

the course of events’.[51]

That evening, Cambon informed George Lloyd, a Conservative M.P. who had spent

some time as an honorary attaché at Constantinople, that:

‘I

have just been to see Sir Edward Grey and he says that under no conditions will

you fight.’ Cambon’s voice almost trembled as he went on to say: ‘That is

what he said. He seems to forget that it was on your advice and under your

guarantee that we moved all our ships to the south and our ammunition to Toulon.

Si vous restez inertes, nos côtes sont

livrés aux Allemands.[52]

While

this argument by itself was spurious, Cambon then made a far more serious

accusation: that Grey had said his hands were tied because the Conservatives

would not support the Government. Despite the hour, Lloyd went to see General

Sir Henry Wilson, no friend of the incumbent Liberal administration, who

apparently confirmed the charge.[53]

Cambon’s allegation set in motion a series of events, orchestrated by Lloyd

and Wilson, which culminated in the delivery of an Opposition pledge of support

for the Government on Sunday, 2 August.[54]

The morning of Saturday, 1 August

began early for Sir Arthur Nicolson, the Permanent Under-Secretary at the

Foreign Office. Just before midnight the previous night an erroneous report had

been received from the French Embassy that the French frontier had been

violated; Nicolson summoned Sir Henry Wilson at 7 a.m. on Saturday to show him a

dispatch ‘indicating that the Germans were about to assume the offensive on

both frontiers’ and, together, they went to see Grey, who was staying at

Haldane’s house in Queen Anne’s Gate. The Foreign Secretary was still asleep

and Nicolson, loathe to wake him (for Grey had been dealing with dispatches till

3.30 a.m.) returned to his own home for breakfast before walking to the Foreign

Office where the news was uniformly bad.[55]

The Cabinet met that morning from 11

a.m. to 1.30 p.m. and it was ‘no exaggeration’ recorded Asquith, ‘to say

that Winston occupied at least half of the time.’ The First Lord was ‘very

bellicose & demanding immediate mobilisation’ which the Cabinet refused

– for the moment – to sanction. Indeed, no sooner had the session commenced

when Grey telephoned the German Ambassador to seek an assurance that, if France

remained neutral in a Russo-German conflict, Germany would not attack the

French. On his own responsibility Lichnowsky gave the assurance sought.[56]

Asquith also wrote to the Chief of the Imperial General Staff at 11.30 a.m. to

put on record the fact that Britain had never promised to send an expeditionary

force to France.[57]

Notwithstanding this faintheartedness, Grey declared (and, given his personal

responsibility in the matter, he had but little option) ‘that if an out &

out & uncompromising policy of non-intervention at all costs is adopted, he

will go.’[58]

Despite making this stand, Grey’s refusal to countenance non-intervention was

not, of course, the same thing as holding out the hope of immediate

participation.

Grey saw Cambon again after the

Cabinet and told him that, in the event of a localized Russo-German conflict,

Germany had agreed not to attack France if she remained neutral. If France, he

added, ‘could not take advantage of this position, it was because she was

bound by an alliance to which we were not parties, and of which we did not know

the terms. This did not mean that under no circumstances would we assist France,

but it did mean that France must take her own decision at this moment without

reckoning on an assistance that we were not now in a position to promise.’ The

Ambassador, with justifiable truculence, replied that he ‘could not and would

not’ transmit such a message.[59]

‘After all that has passed between our two countries’, Cambon exclaimed,

after

the withdrawal of our forces ten kilometres within our frontier so that German

patrols can actually move on our soil without hindrance, so anxious are we to

avoid any appearance of provocation; after the agreement between your naval

authorities and ours by which all our naval strength has been concentrated in

the Mediterranean so as to release your Fleet for concentration in the North

Sea, with the result that if the German Fleet now sweep down the Channel and

destroys Calais, Boulogne and Cherbourg, we can offer no resistance, you tell me

that your Government cannot decide upon intervention? How am I to send such a

message? It would fill France with rage and indignation. My people would say you

have betrayed us. It is not possible. I cannot send such a message. It is true

that agreements between your military and naval authorities and ours have not

been ratified by our Governments, but you are under a moral obligation not to

leave us unprotected.[60]

Cambon

thereupon suggested that he should reply to his Government that the Cabinet had

not yet taken any decision, at which Grey replied ‘that we had come to a

decision: that we could not propose to Parliament at this moment to send an

expeditionary military force to the Continent. Such a step has always been

regarded here as very dangerous and doubtful. It was one that we could not

propose, and Parliament would not authorize unless our interests and obligations

were deeply and desperately involved.’ Nevertheless, Grey at least held out

the hope that a German attack upon the French coast or the violation of Belgian

neutrality ‘might alter public feeling here’ and he promised that he would

‘ask the Cabinet to consider the point about the French coasts.’[61]

Cambon, ‘white and speechless’,

staggered into Nicolson’s room muttering, ‘Ils vont nous lâcher, ils vont

nous lâcher.’ After being seated by the Permanent Under-Secretary, Nicolson

went to see Grey, whom he found ‘pacing his room, biting at his lower lip.’[62]

When informed of the Cabinet decision, Nicolson similarly was left to exclaim,

‘But that is impossible, you have over and over again promised M Cambon that

if Germany was the aggressor you would stand by France.’ Grey replied, ‘Yes,

but he has nothing in writing!’[63]

When Nicolson returned to his own room, Cambon had recovered his composure and

suggested that the time had come to produce ‘mon petit papier’ — the 1912

letter. Nicolson urged the Ambassador not to send an official Note and, instead,

wrote himself to Grey that ‘M Cambon pointed out to me this afternoon that it

was at our request that France had moved her fleets to the Mediterranean, on the

understanding that we undertook the protection of her Northern and Western

coasts. As I understand you told him that you would submit to the Cabinet the

question of a possible German naval attack on French Northern and Western Ports

it would be well to remind the Cabinet of the above fact.’ To this Grey

minuted that he had spoken to Asquith and attached ‘great importance’ to the

point being settled the next day, Sunday 2 August.[64]

Churchill dined alone at the

Admiralty on Saturday night devouring, in addition to his meal, for his appetite

was whetted by the prospect of war, the foreign telegrams as they came in. The

lamps were still not completely extinguished, but flickered dimly; peace hung by

a thread until another box of dispatches arrived containing the news that sent a

gust down Whitehall: Germany had declared war on Russia. Churchill walked across

Horse Guards and entered 10, Downing Street by the garden gate, going up to the

drawing room where a knot of ministers was gathered. After discussing the latest

news, Churchill and Grey left together when, according to Churchill, Grey said

‘You should know I have just done a very important thing. I have told Cambon

that we shall not allow the German fleet to come into the Channel.’ Upon

hearing this, Churchill ‘went back to the Admiralty and gave forthwith the

order to mobilize.’[65]

If true, Grey’s action would have pre-empted the Cabinet discussion the

following day; however, the Foreign Secretary’s account of the conversation

differs crucially from the First Lord’s. According to Grey, he told Churchill

that:

The

French might be sure that the German fleet would not pass through the Channel,

for fear that we should take the opportunity of intervening, when the German

fleet would be at our mercy. I promised however to

see if we could give any assurance that, in such circumstances, we would

intervene.[66]

This

was a different thing altogether.

Sunday’s Cabinet lasted from 11

a.m. to almost 2 p.m. during which the position was, to some extent, clarified.

‘We agreed at last, (with much difficulty),’ wrote Asquith, ‘that Grey

should be authorised to tell Cambon that our fleet would not allow the German

fleet to make the Channel the base of hostile operations.’[67]

It was Grey’s recollection that this pledge had originated from an

‘anti-war’ member of the Cabinet along the lines of, ‘Of course we can’t

have the German fleet come knocking down the Channel, we must stop that.’[68]

On the other hand, Crewe – who could hardly be described as anti-war –

claimed the honour of first raising the point.[69]

Naturally, Grey would not have been a disinterested spectator during these

discussions; it was he, after all, who would have to face Cambon again, and he

thereupon made his position perfectly clear. Perhaps the fairest account is that

of Walter Runciman, who had ‘no record of the guarantee to France of the

English Channel being a suggestion due to the anti-war party. Everyone who

thought about it felt that we could not tolerate the German army at the ports of

the North of France, or the German fleet in the Channel. I never felt that the

Belgian Security Treaty was the big fact. My thoughts were always centred on the

importance to us of the free passage of the English Channel, both for the

purpose of our supplies to London and for the purpose of our easy communication

with the Continent.’ Runciman did not believe that there was either a binding

or a moral obligation to France, but that, simply, ‘a victory for Germany

would be disastrous for us.’[70]

Runciman recalled that the Cabinet

was split three ways, between those determined to resign rather than go to war

(Beauchamp, Morley, Burns and Simon), those who followed what he called the

‘Grey-Asquith view’ which, other than the Prime Minister and Foreign

Secretary, included Churchill, Crewe, Pease and himself, and a middle section

that was still, by Sunday morning, not entirely committed. Typical of the latter

group was Herbert Samuel who now chose to express his own conviction ‘that we

should be justified in joining in the war either for the protection of the

northern coasts of France, which we could not afford to see bombarded by the

German fleet and occupied by the German army, or for the maintenance of the

independence of Belgium’.[71]

The conversion of this middle section, at least to the extent of sanctioning

Grey’s pledge to Cambon, was a crucial determinant in the Cabinet’s later

decision to intervene.[72]

An ancillary, though not unimportant factor (as indicated by McKenna), was that

by Sunday public opinion had turned and was no longer opposed to Britain’s

entry into the War.[73]

Asquith, who was ‘quite clear in my own mind as to what is right &

wrong’, set out his thoughts for his paramour, Venetia Stanley:

(1) We have no obligation of any kind either to France or Russia to give them

military or naval help.

(2) The despatch of the Expeditionary force to France at this moment is out

of the question & wd serve no object.

(3) We mustn’t forget the ties created by the long-standing & intimate

friendship with France.

(4) It as against British interests that France shd be wiped out as a Great

Power.

(5) We cannot allow Germany to use the Channel as a hostile base.

(6) We have obligations to Belgium to prevent her being utilised &

absorbed by Germany.[74]

Was

there ever a more muddle headed piece of thinking? Asquith penned a similar list

for the benefit of the Opposition leaders, which differed only in admitting that

‘Both the fact that France has concentrated practically their whole naval

power in the Mediterranean, and our own interests, require that we should not

allow Germany to use the North Sea or the Channel with her fleet for hostile

operations against the Coast or shipping of France.’[75]

As Asquith calmly attempted to reconcile the irreconcilable, the irony was that

Cambon’s ‘petit papier’, which the Ambassador had threatened to use to

devastating effect, contained the following sentence: ‘The disposition, for

instance, of the French and British fleets respectively at the moment is

not

based upon an engagement to co-operate in war.’ Clearly, either Grey

shamelessly used Cambon’s threat to railroad the rest of the Cabinet, or the

1912 Agreement was not worth the paper it was written on. Even Churchill, who

had warned so forthrightly in 1912 of the dangers of voluntarily surrendering

‘freedom of choice’, now became swept up, exhilarated, by the events

unfolding around him; and as for his senior naval adviser – Battenberg – it

is evident from the note he submitted to Churchill on Sunday morning that the

notion of ‘freedom of action’ was chimerical.[76]

Grey

saw Cambon at 2.30 p.m., after the Cabinet had adjourned, to impart the good

news[77]

and, at the Admiralty shortly thereafter, Churchill (in the presence of

Battenberg and Sturdee) informed Saint-Seine of the Cabinet’s decision. This

was by no means the end of Cambon’s worries though, as Churchill apparently

informed the French Naval Attaché that Grey had also spoken to the German

Ambassador concerning the pledge to France. The Foreign Secretary had to rush to

reassure Cambon that this was quite wrong and nothing would be said to any other

foreign representative until he had had a chance to make a public statement.[78]

Saint-Seine was told that the general direction of the naval war would rest with

the British Admiralty, however, ‘In the event of the neutrality of Italy being

assured, France would undertake to deal with Austria assisted only by such

British ships as would be required to cover German ships in that sea, and secure

a satisfactory composition of the allied fleet. The direction of the allied

fleets in the Mediterranean to rest with the French, the British Admiral

[Troubridge] being junior.’[79]

As vague as this was, it was formalized four days later when a convention was

signed in London by Battenberg and the Assistant Chief of the French Naval

Staff. Section (ii) of this convention stipulated that the French would have

general direction of operations in the Mediterranean, though it was intended

that eventually Troubridge would have some latitude to conduct independent

operations.

The immediate problem, according to

Battenberg, remained the two rogue German ships: ‘So long as the

Goeben

and Breslau are not destroyed or

captured, the British naval forces at present in the Mediterranean will

co-operate with the French fleet in their destruction or capture. When this

operation has been completed the 3 English Battle-Cruisers and 2 or 3 of the

Armoured Cruisers will be released for general service’, while the remainder

of the British forces would be placed directly under the command of the French

C-in-C.[80]

Clearly, Troubridge was correct in his assumption that Milne, being senior to

Lapeyrère, would eventually have to be recalled; however, until this happened

(after the German ships had been disposed of), Milne was still in charge and

Troubridge – not privy to the Admiralty decision – had no valid

justification for his opinion of 2 August that the battle cruisers had been

attached to him permanently.[81]

At the meeting with Saint-Seine on the afternoon of Sunday 2nd, Churchill had

also stated that the package containing the secret signal books could be

distributed and opened — but not yet used. Although this was an advance over

his position the previous Thursday, it was hardly conducive to the fostering of

active co-operation.

The Cabinet reconvened at 6.30 p.m.

that evening, at which time it was learned Germany had invaded Luxembourg.[82]

A last minute appeal by the Counsellor from the German Embassy could not

alleviate the effect of the latest war news: Kühlmann had gone to see Haldane

after the morning Cabinet adjourned to advise ‘England to stand out at first,

and then, after the first shock of arms, to dictate peace by a threat of

intervention.’ Haldane seemed interested by this suggestion but then Grey

appeared and replied, in effect, ‘that he had an honourable obligation to

France.’[83]

The mood at the evening Cabinet had changed: Asquith now ordered the

mobilization of the Army and, with Cabinet approval, Churchill returned to the

Admiralty where, at 7.06 p.m., he sent a signal to Malta authorizing

communication between Milne and Lapeyrère ‘in case Great Britain should

decide to become ally of France against Germany.’[84]

Milne’s War Orders No. 2 – which

had been sent to him in May 1913 – stipulated that a book of signals, labelled

“Secret Package A”, had been prepared for the purpose of joint communication

and that, during a period of strained relations, a cypher telegram would be sent

‘that in the event of war these arrangements are to become operative.’

Manifestly, according to these orders, Milne could only open Secret Package A in

the event of war actually breaking out, which had not occurred when he received

the Admiralty telegram on Sunday evening. In view of this, as he had no other

way of communicating safely with the French, he sought permission to use the

contents of the Secret Package as a cypher immediately, before the formal

declaration of war; in so doing, he was exercising the same caution that

Churchill had shown to Saint-Seine earlier that afternoon.[85]

A signal was duly sent from London at 9.40 the following morning (3 August)

authorizing the use of the cypher; despite this Milne remained unable to contact

Lapeyrère by wireless.

Wireless telegraphy was still in its

infancy and Milne’s abortive attempts to raise the French C-in-C were not

untypical: in Defence, for example,

the W/T room was ‘a funny little iron caboose by the funnels…in the charge

of a Lieutenant of the Royal Marines.’ In this tense period, senior officers

milled around outside wanting to know if the operator could hear anything.

‘Obviously’, a junior officer recorded, ‘they were hoping to get something

direct from the Admiralty which had never been achieved before.’ At this

stage, most of the information came in ‘by land wire and via various

consuls’[86]

and, indeed, there was so much to decode that three watches had to be formed to

handle the task.[87]

Milne continued to send his message to Lapeyrère, detailing the forces

available at his (Milne’s) disposal and wanting to know how best he could

assist the French C-in-C. Having failed to get an answer by the afternoon of

Monday 3 August, Milne dispatched the light cruiser Dublin to Bizerta with a letter for the Senior Naval Officer there,

to be forwarded to the elusive French Admiral; Dublin

would not arrive till 9.43 on the morning of Tuesday the 4th.[88]

Having delivered the letter and departed, Dublin picked up the reply from Bizerta at 3.30 p.m., while at sea,

and relayed it to Milne. The French fleet, it said, consisting of all their

forces, had just left for the Algerian coast.[89]

It was the first hard news Milne had had of the French and it was incorrect as

regards the time: the French fleet had actually departed from Toulon at 4 a.m.

on Monday, 3 August.

Hovering

uncertainly above the heads of the principal French participants was the

tiresome question of the transportation of the XIXth Army Corps, a subject of

controversy between the opposing ministries for over 40 years[90]

until, finally, in May 1913, the Supreme Council of National Defence decreed

that, the arrival of the troops being of paramount importance, the transports

should sail independently, each steaming at its highest speed. A special

division, comprising an obsolete pre-dreadnought and seven old cruisers would be

stationed just to the east of the line Algiers-Toulon, approximately half-way

along the route to be used by the transports, to provide a limited form of close

cover. The main protection for the transports though would be provided by

immediate offensive operations against the enemy by the bulk of the French

fleet: ‘if the enemy were so engaged’, wrote Vice-Admiral Bienaimé, who

would later emerge as one of Lapeyrère’s severest critics, ‘he would not be

free to detach ships to attack the transports; and, in any case, by these

vessels passing singly and at high speed they would be safe, for the target they

presented was small, and the risk to the enemy incommensurate with the gain.’[91]

This would hold true in the case of offensive operations against the Italian or

Austrian fleets, but did not address the problem caused by the presence of

Goeben

and Breslau — fast and powerful

raiders with, apparently, one specific function: disrupting the transportation

of the Algerian Corps.

The most onerous task would devolve

upon Rear-Admiral Darrieus, in command of the special division, patrolling the

midway point of the transports’ route. Darrieus was hardly over-enamoured of

his task, realizing that if Goeben did

break through the offensive cordon his obsolete ships would be the last line of

defence; he therefore requested first that his division be strengthened and

then, in contravention of the long standing arrangement, that the transports be

arranged into convoys to embark from two (not the planned three) ports, Oran and

Algiers. Lapeyrère forwarded these proposals to Paris where they must have

landed like a bombshell upon the desk of the unstable Minister of Marine, Armand

Gauthier, a doctor of medicine knowing next to nothing of naval affairs and who

had achieved his post after a political scandal had caused the removal of his

predecessor.[92]

Gauthier’s increasingly erratic behaviour, which included at one point a

demand that Goeben be attacked before

war had been declared, led to his replacement within days; however, his reaction

to Lapeyrère’s wire was predictable enough. The Admiral had been involved in

all the recent discussions, at which he had made plain he could not spare ships

to escort convoys, and now he wanted to alter a carefully thought out plan on

the very eve of war. Lapeyrère was therefore ordered on 30 July to institute

the plan as originally conceived.

The following day continuing anxiety

about the German ships resulted in the C-in-C seeking permission to send three

old ships of the Division de Complément (Suffren,

Gaulois, Charlemagne), which he had earlier proposed should reinforce

Darrieus’ division, to Bizerta instead to guard against a surprise attack by

the Germans. Not receiving a reply quickly enough to satisfy him, Lapeyrère

telegraphed again that day to the effect that he would dispatch the division on

his own authority unless he received orders to the contrary. Gauthier refused

the request and reiterated his opposition to the formation of convoys.[93]

Although he had agreed to the 1913 plan, Lapeyrère was not an enthusiastic

proponent of it, especially where, in his opinion, the insistence on a timetable

of sailings for the transports hindered his freedom of action and detracted from

the all-out offensive at the outset.

The flaw in the plan had always been

that the troops were to be sent before French command of the seas had been

guaranteed. Lapeyrère now had to weigh in his own mind the consequences of a

disaster befalling the XIXth Army Corps – upon whose presence at the front the

army apparently set so much store – against the possible lost opportunity of

an early victory at sea. The final version of the French Army’s infamous Plan

XVII, effective from 15 April 1914, stipulated that the 37 steamers to be used

to transport the troops were to leave between the third and seventh days of

mobilization; convoys could be formed if adjudged essential but only if no

significant delay resulted.[94]

It was this let-out clause that Lapeyrère now wanted to utilize. His position

was undoubtedly complicated in late July by the ambiguity of the attitudes of

Italy and Britain: although he could, in all probability, count on the former

declaring neutrality and the latter coming in as an ally of France, he could not

be absolutely sure. And, by the first days of August, the clarification of this

situation had been offset by the confusion reigning in Paris which in turn was

exacerbated by the command structure, by friction between the C-in-C and the

Naval Staff, and, above all, by the forlorn figure of Dr Gauthier. The hapless

Minister, having ‘forgotten’ to order torpedo boats into the Channel, now

wanted, on 2 August, to attack the Germans immediately, then proceeded to

challenge the War Minister to a duel and finally broke down in tears, leading

the President to conclude, somewhat euphemistically, that Gauthier’s nerves

were on edge.[95]

In the crisis the situation in the

Mediterranean was overlooked until the Cabinet, having regained some of its

composure later in the afternoon, drafted a telegram to Lapeyrère on the basis

of the latest information of the German ships, which placed them at Brindisi on

the night of 31 July/1 August. These orders, received by Lapeyrère at 8.50 p.m.

on Sunday evening, 2 August, instructed him to set sail to try to intercept

Goeben

and Breslau and reiterated the

necessity to have the transports proceed independently. So important was this

deemed that the Minister of War, Messimy, accepted responsibility for all risks.[96]

Despite this generous offer, Lapeyrère remained unhappy; uncertainty surrounded

him. As early as 30 July the Cabinet had voluntarily withdrawn all French troops

ten kilometres from the frontier: this order had been reaffirmed by Messimy on 1

August while German mobilization continued apace. Only on the 2nd, that perilous

Sunday, did the arguments of General Joffre prevail: the territory abandoned

would, if captured by the Germans, have to be retaken later with great loss of

life. Even so, French desperation to portray Germany as the aggressor led Joffre

to declare on 3 August that no French troops must cross the frontier; any

‘incidents’ must arise as a result of German provocation.[97]

Lapeyrère’s position was more

difficult: the enemy he had planned to oppose, Italy, showed no signs of joining

the fray, while he could not afford to let the German ships make the first move

as, in all probability, this move would be not some minor incident but the

sinking of a troop transport. In the circumstances, despite his earlier

willingness to allow independent sailing, he had now convinced himself that only

by convoy could the XIXth Army Corps be transported safely. Late on the night of

Sunday 2nd he telegraphed Paris again, setting out a virtual list of demands:

his fleet would sail so as to be off the African coast on the afternoon of the

4th; he had ordered the transports to stay in harbour; and convoys were

essential. As Sunday became Monday Lapeyrère received accurate information that

Goeben

had been in Messina on the

previous day; finally, some hours later, at 4 a.m. on 3 August, the main body of

the French fleet weighed anchor and proceeded majestically, if hardly noticed,

out of Toulon harbour.

|

[1] Admiralty to C-in-C, Medt., no. 176, 27 July 1914, PRO Adm 137/HS19.

[2] Milne to Admiralty, 20 August 1914, para. 2, PRO Adm 137-879; Lumby,

p. 213.

[3] Statement by Captain Francis W Kennedy, HMS

Indomitable, 20 October 1914, King’s College Centre for Military

Archives, Kennedy 3 [this important source was written by Kennedy when he

feared he might be made a scapegoat for the Goeben

affair after hearing certain rumours to that effect; hereinafter referred to

as “Kennedy”]. See also, Journal of Midshipman (later Vice-Admiral) B B

Schofield, HMS Indomitable, 27

July 1914, IWM BBS 2.

[4] It was only in December 1913 that Churchill had announced that,

during 1914, four battle cruisers would be ‘kept based on Malta’, but

that ‘If the Germans continue to keep their battle-cruiser Goeben

in the Mediterranean, the British force there will be re-inforced by the New

Zealand as soon as the Tiger

joins the 1st. Battle-Cruiser Squadron at the end of 1914.’ Navy

Estimates, 1914-15, Memorandum by Churchill, 5 December 1913, PRO Cab

37/117/86; Lumby, p. 116.

[5] Churchill to Battenberg, 28 July 1914, First Lord’s Minutes, Naval

Historical Library; World Crisis,

p. 120.

[6] Journal of Lieutenant Parry, HMS

Grasshopper, Wed., 29 July 1914, IWM 71/19/1.

[7] Asquith to the King, 30 July 1914, PRO Cab 41/35/22.

[8] Admiralty to C-in-C, Mediterranean, Senior Naval Officer, Gibraltar,

Admiral Superintendent, Malta, 29 July 1914; Admiralty to C-in-C, no. 179,

29 July 1914. PRO Adm 137/HS19; Lumby, p. 145.

[9] Admiralty to C-in-C, Medt., no. 183, 30 July 1914, PRO Adm 137/HS19;

Lumby, p. 146 gives the final version. Note: Dan van der Vat, The

Ship that Changed the World, (London, 1985) pp. 65-7, makes too much of

the slightly altered version appearing in The

World Crisis and, in particular, the change from “Goeben which” – clearly what Churchill intended – to “Goeben

who” which appeared in the telegram Milne received. Churchill was in the

habit of always abbreviating “which” to “wh” — either the

Admiralty code clerk did not understand this, misread what Churchill had

written, or decided to improve on the grammar. As first drafted, the

offending piece read: “...fast German or Austrian ships wh may

interfere...”. This called for “which”. Churchill then altered it to

read: “...fast German ships particularly Goeben

wh may interfere...”. This again called for “which” though it is easy

to imagine the code clerk substituting “who” in the belief that it

referred to Goeben alone; but,

whatever else Churchill may be held responsible for, this particular error

was not his.

[10] ‘These directions on which the First Sea Lord and I were completely

in accord,’ Churchill wrote in The

World Crisis [p. 131], ‘gave the Commander-in-Chief guidance in the

general conduct of the naval campaign; they warned him against fighting a

premature single-handed battle with the Austrian Fleet in which our

battle-cruisers and cruisers would be confronted with Austrian Dreadnought

battleships; they told him to aid the French in transporting their African

forces, and they told him how to do it, viz. “by covering and, if

possible, bringing to action individual fast German ships, particularly Goeben.”

So far as the English language may serve as a vehicle of thought, the words

employed appear to express the intentions we had formed.’

[11] Fisher to his daughter, Dorothy Sybil Fullerton, 31 July 1914,

Fullerton mss., NMM FTN 7/2.

[12] Journal of Midshipman A de Salis, HMS

Defence, 31 July 1914, IWM 76/117/1.

[13] C-in-C, Medt. to Admiralty, no. 375, 31 July 1914, PRO Adm 137/HS19;

Lumby, p. 146.

[14] Admiralty minute sheet, 31 July 1914, PRO Adm 137/HS19.

[15] Milne to Admiralty, 20 August 1914, para. 8, PRO Adm 137/879; Lumby,

p. 214; Sir Julian Corbett, Naval

Operations, vol. I, p. 35.

[16] Rome to Admiralty, no. 43, 1 August 1914, rec’d 9.41 p.m.; Ad.

Supt., Malta, via S.N.O. Gibraltar to Admiralty, no. 47, 1 August 1914,

rec’d 1.20 a.m., 2 August. PRO Adm 137/HS19; Lumby, p. 147. Breslau

had stopped at Brindisi to disembark Dönitz on his mission to organize

colliers; Goeben’s attempt to

coal later the same day was forestalled by the Italians.

[17] Captain’s clerk Lawder quoted in, Liddle, The

Sailor’s War 1914-1918, p. 29.

[18] Churchill to Battenberg and Sturdee, 2 August 1914, PRO Adm 137/879.

[19] Minute by Battenberg, ibid.

[20] Minute by Sturdee, ibid.

[21] Admiralty to C-in-C, Medt., no. 196, sent 1.30 p.m., 2 August 1914,

PRO Adm 137/HS19; Lumby, p. 147.

[22] Midshipman’s Journal, B. B. Schofield, 2 August 1914, IWM BBS 2.

[24] E. C. T. Troubridge, Rough

Account of “Goeben” and “Breslau”, Lumby, p. 417.

[25] Fisher himself disagreed with this contention. See, Fisher to

Churchill, 31 March 1913, WSC Comp.

vol II, pt iii, p. 1937. Large armoured cruisers had become obsolete

with the introduction of the battle cruiser, but this left a gap for

scouting and patrol work which was duly filled with the laying down, in

1909, of the Bristol class of light cruiser. Subsequent classes followed

and, despite his misgivings, Churchill sanctioned the construction of a

further eight in the 1913 Estimates. Soon after, the First Lord developed

his own theory as to how these light cruisers should be deployed: ‘It is

suggested’, he informed Admiral Sir Henry Jackson, ‘that the light

cruiser squadrons … should work with the battle cruiser squadron, and that

in observation or scouting the battle cruiser should be in the front line

with the light cruisers of his group perhaps 5 or 6 miles in rear of it. At

any rate the battle cruiser would be an essential part of the very front

line in the closest contact with the enemy; the armoured cruiser squadrons

lying distinctly further back in support.’ Churchill to Jackson, 3 April

1913, WSC Comp. vol II, pt iii,

pp. 1721-2.

[26] Minutes of the Proceedings of a Court of Inquiry, 22 September 1914,

Lumby, p. 253.

[27] Vice-Admiral Sir F. C. D. Sturdee, Report

on the Principal Cruiser Work Carried Out by the Home Fleets During 1913,

Admiralty War Staff, Operations Division, July 1914, PRO Adm 1 8388/227.

[28] Troubridge recorded in a statement, presented to the Court of Inquiry

in September, that: ‘Admiral Sturdee in his book which is issued that I

received about a fortnight ago, says that the day of the armoured cruiser is

gone. From the result of the experiments in the North Sea he deduces that

they must never separate, and all he will permit himself to say is that they

will do some useful cruiser work under the aegis of a Fleet and they might

do something against a battle-cruiser, showing the great risk in his

opinion, which is considered very authoritative.’

[29] Minutes of Proceedings at a Court Martial, held on board HMS Bulwark at Portland, 5-9 November 1914. Statement for the

Defence; Lumby, p. 367.

[30] Court Martial, qu. 5, Lumby, p. 247.

[31] Court Martial, qu. 169, Lumby, p. 294.

[32] Sailing Orders, Rear-Admiral, First Cruiser Squadron, 2 August 1914,

PRO Adm 137/879; Lumby, pp. 149-50.

[33] Decypher, Mr Sinclair, Brindisi, no. 7 urgent, 2 August 1914. PRO Adm

137/HS19; Lumby, p. 147.

[34] Admiralty to C-in-C, Medt., no. 198, 2 August 1914, PRO Adm 137/HS19.

[35] Court Martial, qu. 5, Lumby, p. 247.

[36] Court of Inquiry, statement by Troubridge, Lumby, p. 254; qu. 27,

Lumby, p. 266.

[37] Court Martial, Statement for the Defence, Lumby, p. 368.

[38] Note: this appears in the original, PRO Adm 137/879, p. 62, but is

excluded from the extract given in Lumby, pp. 149-50.

[39] On 22 July Milne had been ordered to assume command at Admiralty

House, Chatham, on 30 August.

[40] Wireless Telegraph Signal Log, HMS

Defence, IWM MISC 64 ITEM 1009.

[41] Kennedy, p. 2; see also, E Keble Chatterton, Dardanelles

Dilemma, (London, 1935), pp. 19-20.

[42] Court of Inquiry, qu. 13, Lumby, p. 250.

[43] W/T Signal Log, HMS Defence,

IWM MISC 64 ITEM 1009.

[44] Log of HMS Indefatigable,

PRO Adm 53/44809.

[45] Midshipman’s Journal, B. B. Schofield, 2 August, IWM BBS 2.

[46] C-in-C to Admiralty, no. 386, 2 August 1914, rec’d 7 p.m.; pencil

annotation by Battenberg, 2 August, PRO Adm 137/HS19.

[47] Admiralty to C-in-C, Medt., no. 204, sent 12.50 a.m., 3 August 1914,

PRO Adm 137/HS19, Lumby. p. 150.

[48] Churchill later argued, in The

World Crisis, that ‘it happened in a large number of cases that,

seeing what ought to be done and confident of the agreement of the First Sea

Lord, I myself drafted the telegrams and decisions in accordance with our

policy and the Chief of the War Staff took them personally to the First Sea

Lord before despatch.’

[49] Martin Gilbert, Winston S

Churchill, vol. III, pp. 18-9.

[50] Nicolson subsequently informed Hardinge: ‘On Saturday Cambon

pointed out that at the request some time ago of our Admiralty the French

had sent all their fleet to the Mediterranean on the understanding that we

would protect their northern and western coasts. This was a happy

inspiration on the part of Cambon and to this appeal there could be but one

answer…’ Nicolson to Hardinge, private, 5 September 1914, Nicolson mss.,

PRO FO 800/375. Only one answer there may have been, but it had nothing to

do with the 1912 letter which specifically denied the pledge Cambon was now

trying to redeem.

[51] Asquith to Venetia Stanley, 31 July 1914, Asquith

Letters, no. 111, p. 138.

[52] Charmley, Lord Lloyd, p.

33.

[54] For the part played by the Conservatives, see appendix i.

[55] Callwell, Wilson, vol. I,

p. 153; Nicolson, Lord Carnock, pp.

418-9; Cameron Hazlehurst, Politicians

at War, (London, 1971), p. 91.

[56] Lichnowsky to Jagow, tel. no. 205, 1 August 1914, given in, Geiss

(ed.), July 1914, no. 170, p. 343.

Note, however, that Lichnowsky himself later referred to a

‘misunderstanding’ in this telegram as ‘Sir Edward Grey had meant that

Germany should then remain altogether neutral, even in a war between Austria

and Russia.’ Lichnowsky, Heading for

the Abyss, p. 414, n. 1.

[57] Sir Henry Wilson, diary entry for 1 August 1914, quoted in Callwell, Wilson,

vol. I, p. 154. See also Hazlehurst, Politicians

at War, p. 90 which tries to make some sense of Asquith’s

“impenetrable” intentions.

[58] Asquith to Venetia Stanley, 1 August 1914, Asquith

Letters, no. 112, pp. 139-40; Narrative by Professor Temperley, Spender

mss., BM Add MSS 46386.

[59] Grey to Bertie, tel. no. 299, 1 August 1914, BD, XI, no. 426.

[60] Conversation between Grey and Cambon quoted in, Henry Wickham Steed, Through Thirty Years, vol. II, pp. 14-5.

[61] Grey to Bertie, tel. no. 299, 1 August 1914, BD, XI, no. 426.

[62] Nicolson, Lord Carnock, p.

419.

[63] Diary of Henry Wilson, quoted in, Hazlehurst, Politicians

at War, p. 88. Note: this record of the conversation was excised in

Callwell’s biography.

[64] Nicolson to Grey, private, 1 August 1914, BD, XI, no. 424.

[65] Churchill, World Crisis, p.

127.

[66] Narrative by Professor Temperley, Spender mss., BM Add MSS 46386 [my

emphasis].

[67] Asquith to Venetia Stanley, 2 August 1914, Asquith

Letters, no. 113, pp. 145-7. ‘Was ever anything heard like this?’

recorded Sir Henry Wilson. ‘What is the difference between the French

coast and the French frontier?’ Diary entry for 2 August, Callwell, Wilson, vol. I, p. 155.

[68] Notes of an Interview between Grey and Temperley, Spender mss., BM

Add MSS 46386.

[69] Crewe to Temperley, 8 May 1929, Spender mss., ibid.

[70] Runciman to Temperley, 4 November 1929, ibid.

[71] Samuel to his wife, 2 August 1914, in Lowe & Dockrill, Mirage of Power, vol. III, pp. 489-91.

[72] For an examination of the various factors, including the part played

by the Opposition, see Wilson, The

Policy of the Entente, chapter 8.

[73] McKenna to Spender, 8 May 1929, ibid.

Sir Henry Wilson recounts that, by 10 o’clock that evening, cheering

crowds had gathered outside Buckingham Palace: diary entry, 2 August 1914,

Callwell, Wilson, vol. I, p. 155.

[74] Asquith to Stanley, 2 August 1914, Asquith

Letters, no. 113, pp. 145-7. See also, Hazlehurst, Politicians at War, pp. 96-7 and, in particular, his comment that,

‘The bland disingenuousness of the first and third points, and the

breathtaking strategic ignorance of the second, reveal the extent to which

the cabinet’s deliberations had resulted in a convergence of views.’

[75] Memorandum by Asquith, 2 August 1914, quoted in, Blake, The Unknown Prime Minister, pp. 223-4. The following day, the German

Foreign Minister pledged that the northern coasts of France would not be

threatened so long as Britain remained neutral. By then, it was too late.

Jagow to Lichnowsky, tel. no. 216, 3 August 1914, German

Diplomatic Documents, no. 714, p. 520.

[76] This was when Battenberg declared that British forces were massed in

the North safeguarding French interests, while French forces in the

Mediterranean helped to safeguard British interests. Battenberg to

Churchill, 2 August 1914, PRO Adm 137/879.

[77] Cambon was informed: ‘In case the German fleet came into the

Channel or entered the North Sea in order to go round the British Isles with

the object of attacking the French coasts of the French navy and of

harassing French merchant shipping, the British fleet would intervene in

order to give to French shipping its complete protection, in such a way that

from that moment Great Britain and Germany would be in a state of war.’

Cambon to Viviani, 3 August 1914, given in, Geiss (ed.), July

1914, no. 183, p. 356.

[78] Grey to Cambon, 2 August 1914, Grey mss., PRO FO 800/55.

[79] Précis of conversation, Admiralty, 2 August 1914, PRO Adm 137/988; WSC

Comp. vol. III, pt. i, pp. 11-12.

[80] Anglo-French Convention, London, 6 August 1914, PRO Adm 137/988;

Lumby, pp. 431-2; Halpern, Naval War

in the Medt., pp. 26-7.

[81] Milne was subsequently recalled on 12 August.

[82] After the morning Cabinet, Samuel, Lloyd George, Simon, Morley,

Harcourt, Pease and others lunched at Lord Beauchamp’s and discussed the

situation where, according to Samuel’s letter that day to his wife, they

all agreed with his formula that British intervention would be dependent

upon a substantial violation of Belgium neutrality. See, Samuel to his wife,

2 August 1914, Lowe & Dockrill, Mirage

of Power, vol. III, pp. 489-91. However, some years later, Samuel

maintained that, in the informal afternoon discussions, ‘no definite

conclusions were reached. It had become fairly clear that the Belgian issue

would arise in the most acute form.’ See, Samuel to Temperley, 24 June

1929, Spender mss., BM Add MSS 46386. In either event it had become obvious

that Asquith would stand or fall with Grey.

[83] Interview with Kühlmann, 22 February 1929, in G P Gooch, Studies in Diplomacy and Statecraft, (London, 1942), pp. 82-3.

[84] Admiralty to C-in-C, Malta, C-in-C, Hong Kong, no. 200, sent 7.6

p.m., 2 August 1914, PRO Adm 137/HS19; Lumby, p. 148.

[85] C-in-C to Admiralty, no. 387, 2 August 1914, PRO Adm 137/HS19; Lumby,

p. 149. Note: van der Vat, The Ship

that Changed the World, pp. 68-9, accuses Milne of being at fault for

sending this telegram when it ‘should have been obvious from his general

orders’ [i.e. War Orders No. 2]. However these specifically prohibited

Milne from using Secret Package A until war had been declared.

[86] G. H. Warner, Recollections of

a Junior Officer on HMS Defence, IWM P389.

[87] Captain’s clerk Lawder in, Liddle, The

Sailor’s War 1914-1918, p. 33.

[88] C-in-C to Admiralty, no. 392, 3 August 1914, PRO Adm 137/HS19; Lumby,

p. 153. Log of HMS Dublin, PRO Adm

53/40233.

[89] Admiral, Bizerta to C-in-C, via Dublin,

sent 1.50 p.m., rec’d 3.30 p.m., 4 August 1914. Naval Staff Monographs,

vol. VIII, the Mediterranean, 1914-15, appendix B. Operations

Signals extracted from the logs of various ships. PRO Adm 186/618

[hereinafter referred to as NSM,B].

[90] This dispute is summarized in Halpern, Medt

Naval Situation, pp. 135 ff.

[91] Vice-Admiral Bienaimé, quoted in The

French Fleet in the Mediterranean, August 1-7, 1914, The Naval Review,

1919, vol. 7, p. 494.

[92] Barbara Tuchman, August 1914,

(London, p’back, 1980), p. 91.

[93] Captain Voitoux, writing in Revue

Politique et Parlementaire, quoted in Naval Review, 1919, vol. 7.

[94] Halpern, Medt Naval Situation,

p. 144.

[95] Tuchman, August 1914, pp.

149-50.

[96] Capt. Voitoux, op. cit.

[97] Brigadier-General E L Spears, Liaison,

(London, 1930), pp. 10-11.

|

|

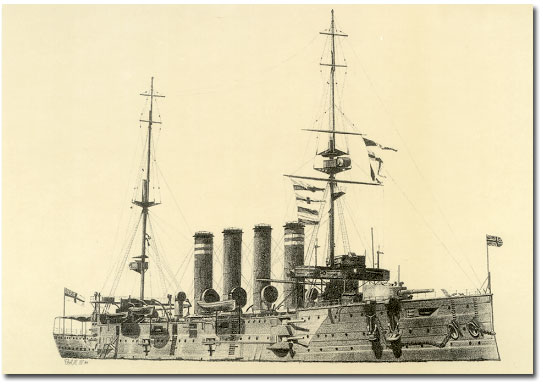

Ships of the Victorian & Edwardian Navy :

I have been drawing the ships of the

Victorian and Edwardian Navy for twenty

years for my personal pleasure and I am

including some of these drawings on this

site in the hope that others may find them

of interest.

The original drawings are all in pencil.