The STRAITS Trilogy

Volume I: Superior Force : the conspiracy behind the escape of Goeben and Breslau Volume II: Straits : British Policy towards the Ottoman Empire and the Origins of the Dardanelles Campaign Volume III: The Millstone : British Naval Policy in the Mediterranean, 1900-1914, the Commitment to France and British Intervention in the War

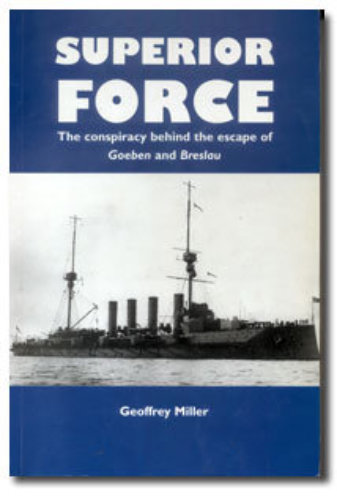

Superior Force

The Conspiracy Behind the Escape of Goeben and Breslau xxiii + 458 pages 20 illustrations 2 maps Full bibliography, notes and index Laminated card cover, 6¼"x9¼" ISBN 0 85958 635 9 Published 1996Straits

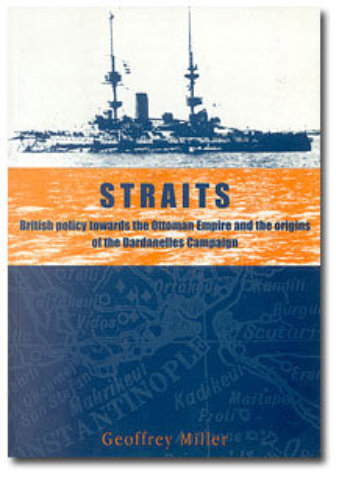

British Policy Towards the Ottoman Empire and the Origins of the Dardanelles Campaign xxvi + 604 pages 12 illustrations, 1 map Full bibliography, notes and index Laminated card cover, 5¾"x8¼" ISBN 0 85958 635 9 Hardcover ISBN 0 85958 663 4 Published 1997The Millstone

British Policy in the Mediterranean, 1900-1914, the Commitment to France and British Intervention in the War xv + 611 pages Full bibliography, notes and index Laminated card cover, 5¾"x8¼" ISBN 0 85958 690 1 Published 1999

As the range of our activities is so diverse, we have a number of different websites. The main Flamborough Manor

site, which is where you are now, focuses primarily on accommodation (bed & breakfast) but has brief details of all

our other activities. To allow for more information to be presented on these other activities, we have other self-

contained web-sites and some of the links you will encounter while browsing these pages will take you to these

separate sites. To return to this site, simply go to the LINKS page, which is common to all our sites.

Views of Flamborough Head

The Manor House, Flamborough, Bridlington, East Riding of Yorkshire. YO15 1PD

Telephone: 01262 850943 [International: +44 1262 850943]

E-mail: gm@flamboroughmanor.co.uk

Web-site design & content Copyright © 2025 Geoffrey Miller

These books provide a comprehensive account of British naval and diplomatic policy in the two decades

prior to the Great War, focusing in particular on the escape of the German ships Goeben and Breslau

[Superior Force], the origins of the Dardanelles Campaign [Straits], and the political and diplomatic

imperatives behind the British decision to enter the war in August 1914 [The Millstone].

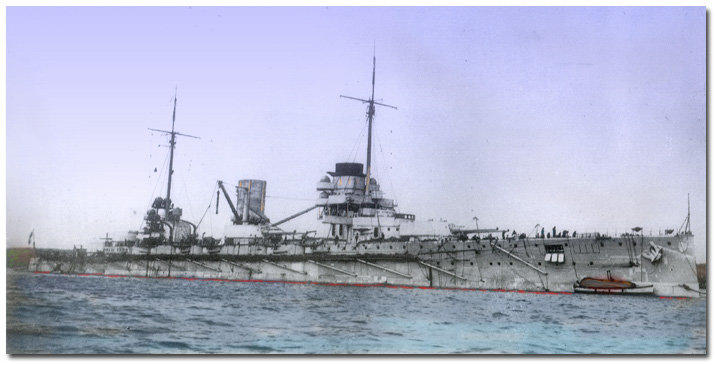

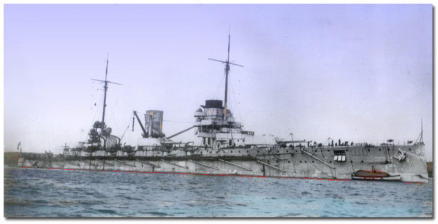

SMS Goeben

Superior Force

The Conspiracy Behind the Escape of Goeben and Breslau

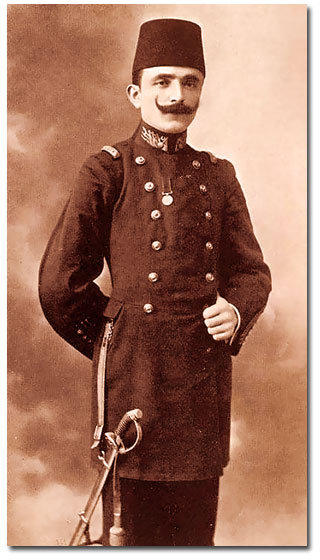

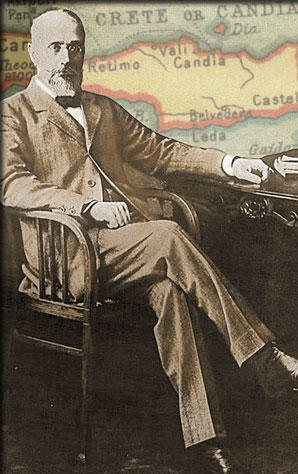

Synopsis : In the first weeks of August, 1914 the German battle cruiser, Goeben, and her accompanying light cruiser, Breslau, escaped the clutches of the pursuing British Mediterranean Squadron and took refuge at Constantinople, where they would later exert a decisive influence upon Turkey’s attempts to remain out of the war. In October 1914, with the connivance of the Turkish Minister of War, but against the wishes of the majority of the Turkish Cabinet, the German Admiral at the head of the Turkish Navy single- handedly forced the issue. At the helm of Goeben, Admiral Souchon manoeuvred into the Black Sea and deliberately shelled Russian ships, ports and shore installations. The Turks, reluctant to the last, were finally catapulted into the War. Yet, would this outcome have eventuated without the presence of Admiral Souchon and Goeben? The Turkish fleet by itself was too weak to risk a sortie in the Black Sea. Without Goeben could the issue have been forced? Meanwhile, the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, actively sought Greek co-operation for a planned major offensive against the Turks at the Dardanelles. His plea for assistance reached the British Officer at the head of the Greek Navy, Rear-Admiral Mark Kerr, who set impossible conditions which he knew would result in the proposal being rejected in London. What Churchill did not know, and which has never previously been revealed, was that Kerr had not only removed any chance of Greek participation at the Dardanelles, but had also been instrumental in the conspiracy afoot in Athens during August to allow the German ships to escape in the first place. Various accounts of the escape have sought to apportion blame, with the Admiralty (under Churchill), the Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean, and the Rear-Admiral, First Cruiser Squadron all being found culpable to some extent. What no previous account has revealed however is the fact that there was an organized conspiracy afoot in Athens, involving the Greek Premier on one side, and the King and a serving British Rear-Admiral on the other, to facilitate the escape of the German ships. The eventual destination of Goeben and Breslau (a mystery to the British until the ships actually reached the Dardanelles) was common knowledge amongst ruling circles in Athens some hours before Britain declared war on Germany. Privy to this secret was Rear-Admiral Mark Kerr, the British Officer at the head of the Greek Navy. For three vital days Kerr kept the secret to himself; then, when it was almost too late, he fed the Admiralty clues which were, however, not acted upon. In addition to being the most complete account of the dramatic escape yet published, Superior Force, for the first time, reveals the extent of the Athens conspiracy and the ambivalent rôle played by Mark Kerr who, soon after, would also remove any chance of Greek co-operation in the major offensive planned by Churchill against the Turks at the Dardanelles. Few men can genuinely be said to have changed history; by his actions in Athens in the summer of 1914 Mark Kerr is one of those few.

Straits

British Policy Towards the Ottoman Empire

and the Origins of the Dardanelles Campaign

Synopsis : On 19 February 1915 the guns of the massed Anglo-French fleet off Cape Helles opened fire on targets on the European and Asiatic shores of the Ottoman Empire. The Dardanelles campaign had begun. There is, however, little in-depth analysis of the way in which the campaign came about. Turkey’s pre-war alignment with Germany culminated with the signatures of the German Ambassador and Turkish Grand Vizier on the formal Treaty of Alliance on the afternoon of Sunday, 2 August 1914, but for months the treaty remained no more than a scrap of paper. The Turks mobilized only as fast as their moribund economy allowed while at the same time continuing to give the outward appearance of an anxious, if hardly disinterested, neutral. The menacing days of August passed; the Turks prevaricated, neither in the War nor immune from it. Unable to contain himself any longer, the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, actively sought Greek co-operation for a planned major offensive against the Turks at the Dardanelles. His plea for assistance reached the British Officer at the head of the Greek Navy, Rear-Admiral Mark Kerr, who set impossible conditions which he knew would result in the proposal being rejected in London. With his plans having thus gone awry, Churchill turned his gaze away from the plain of Troy — temporarily. By October, 1914 the patience of the Germans had also snapped. With the connivance of the Turkish Minister of War, but against the wishes of the majority of the Turkish Cabinet, the German Admiral at the head of the Turkish Navy single-handedly forced the issue. At the helm of the magnificent battle cruiser Goeben, which had escaped from the pursuing British Squadron in the first days of the war and had sought refuge at Constantinople, Admiral Souchon steamed into the Black Sea and deliberately shelled Russian ships, ports and shore installations. The Turks, reluctant to the last, were finally propelled into the war. Yet, would this outcome have eventuated without the presence of Souchon and Goeben? The Turkish fleet by itself was too weak to risk a sortie in the Black Sea. Without Goeben could the issue have been forced? Now that the Turks had become involuntarily embroiled in the War, Churchill’s eyes once more turned eastward. STRAITS takes the opening bombardment at the Dardanelles not as the starting point but as its culmination in an endeavour to explain how it was that Turkey was aligned with Germany — a ruinous alliance which was by no means preordained. British diplomatic policy towards the Ottoman Empire failed comprehensively when the result could have been so different. Why, for example, was every Turkish appeal for an alliance with Britain rebuffed? The Young Turk revolution of 1908 presented the British Foreign Office with a quandary — to support the new régime, which had successfully restored the constitution, or continue to remain aloof, as had been the policy during the reign of Abdul the Damned. Support was grudgingly provided but the improved British position at the Sublime Porte was jeopardized by two events: the new Ambassador, who was deeply antagonistic to the new régime, and the Anglo-Russian convention which meant that the British Foreign Secretary had to try somehow to support the Turks without alienating the Russians. The common thread running through the book is the struggle to control the Straits of the Dardanelles and Bosphorus from the period when the British Squadron at Malta commanded the Mediterranean Sea unopposed at the turn of the century through to the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire first as a result of the Turco-Italian and Balkan Wars and then following Turkey’s forced, and ultimately disastrous, entry into World War I. This struggle encompassed Russian aspirations, Greek ambition, French colonial ardour and British Imperial and oil considerations — all underpinned by the constant desire of the Turks themselves to prevent the collapse of their Empire. British diplomatic policy towards the Ottoman Empire failed comprehensively when the result could have been so different.

The Millstone

British Policy in the Mediterranean, 1900-1914, the

Commitment to France and British Intervention in the War

Synopsis : At half past two on the afternoon of Sunday, 2 August 1914, Sir Edward Grey, the Foreign Secretary, informed the French Ambassador of the decision just reached by the British Cabinet — despite not yet being at war with Germany, if, nevertheless, the German High Seas Fleet ventured out from its base, the British fleet ‘would intervene … in such a way that from that moment Great Britain and Germany would be in a state of war.’ What led to the giving of this pledge? Was there an obligation on Britain’s part, or merely a commitment, moral or otherwise, to intervene in certain circumstances? The Foreign Secretary subsequently declared in his own defence that the promise to the French ‘did not pledge us to war.’ Grey was, however, wrong — once the promise was made, British entry into the war was certain. Despite this, a group within the Cabinet spent the afternoon of Sunday 2 August desperately searching for an issue around which they could group, and which would provide a more convenient excuse for British entry into the war than one based upon a moral commitment to France; that excuse was to be Belgian neutrality. Two things virtually guaranteed British entry in the war: the secret Anglo-French military and naval talks, which commenced in 1906, and the naval position in the Mediterranean. With Austria and Italy both constructing dreadnoughts, and facing the German naval challenge, British command of the Mediterranean could no longer be guaranteed. Similarly over-extended, the French were unable to protect both their Atlantic and Mediterranean coastlines. From strategic necessity came political expediency. The Millstone will show: • That Grey was more aware of what was settled by the secret military conversations than he pretended to be. • That the situation created by the German naval programme gave Britain no option other than to evacuate the Mediterranean. • That Anglo-French naval co-ordination and strategic planning remained chaotic. • That the Cabinet could not have prevented Britain’s entry into the war; all they could have done was to prevent the formation of a coalition Government. • That the pledge to France and consideration of British interests were the sole determinants of Britain’s entry. • That the German promise in August 1914 not to attack the French coast was irrelevant. • That, far from informing the German Government of the pledge given to Cambon as he claimed, Grey was determined to conceal this fact until Monday, 3 August. • That the issue of Belgian neutrality was used in August 1914 to assuage consciences and prevent the formation of a coalition Government, but was not crucial to the decision to intervene. • That the Continental policy, committing British troops to fight in Europe, was decided upon in August 1911 by a small inner circle of the Cabinet who knew precisely what it would entail.

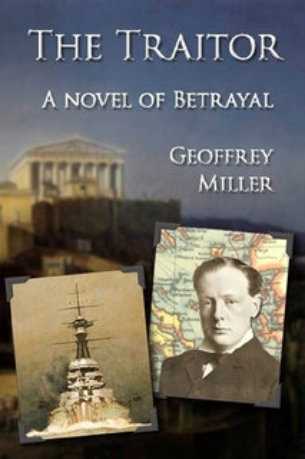

Based on "Superior Force" the acclaimed study of

the escape of Goeben and Breslau :

"The Traitor" is firmly grounded in fact. The majority of the people referred to in the novel took part in the actions described. Many of the conversations are based on diary entries, memoranda and letters subsequently published by the main protagonists. The principal exception to this is the character of Major Lionel Samson. When he first appears, Samson is, as he was in fact at the time, the British Military Consul at the siege of Adrianople in 1913. By 1915 he was, in real life, in charge of the allied espionage network based in Athens. However, between these two dates, all actions ascribed to him in The Traitor are fictional. On the other hand, the other main character, Admiral Mark Kerr is portrayed throughout as he was during the period. His actions, however implausible, are firmly based on the research gathered for my non-fiction studies of the events of this period, Superior Force, Straits and The Millstone. During the first week of August, 1914, Admiral Mark Kerr faced a desperate choice: betray his conscience or his country. It was a choice he faced in real life, where his attempt to reconcile the competing demands of his service to Britain and Greece failed. Major Lionel Samson’s principal experience of betrayal stemmed from a more personal encounter: an affair which ends when fate (according to Edith Roberts) intervenes. The sense of loss — and betrayal — Samson feels is heightened as, at that time, he does not believe in fate, or the pre-ordained workings of some exterior force, either for good or evil. Forced to reconsider his own deeply held beliefs, Samson is also disillusioned when everyone he encounters in Athens appears to operate on two different levels, and betrayal, at both personal and official levels, is rampant. Professor Geroulanos, for example, while certainly calling himself a Greek patriot, belongs to an organization whose only aim is the furtherance of German influence in his country (another example of the activities of a real-life character being mirrored in The Traitor). Even within the confines of the British Legation Samson comes to suspect that senior officials are hiding something. And, finally, the agent he employs is also working for someone else. Samson is forced to consider the prospect that the ability to betray, to lie at will, is part of man’s nature. Then, however, his life is saved by the same Professor Geroulanos he suspects of treason; his closest ally within the Legation is converted to share his suspicion regarding the Greek Premier; and his own agent, the Greek porter, posthumously provides the evidence to help resolve the final part of the puzzle — the identity of the traitor. Samson is almost re-converted into disbelieving the workings of a malign fate until a moment’s cowardice, which he later excuses by reasoning it was pre-ordained, results in his final test.

The Manor House

Accommodation, Books, Traditional Knitwear & Hand-Knitted Ganseys, Breton shirts

Lesley Berry and Geoffrey Miller

The Manor House

Flamborough

Bridlington

East Riding of Yorkshire YO15 1PD

United Kingdom

Telephone: 01262 850943 (Mobile 07718 415234)

International: +44 1262 850943

E-mail: gm@flamboroughmanor.co.uk

Ships of the Victorian &

Edwardian Navy :

I have been drawing the ships of the Victorian and Edwardian Navy for thirty years for my personal pleasure and I am including some of these drawings on this site in the hope that others may find them of interest. The original drawings are all in pencil. Reducing the file size and therefore the download time has resulted in some loss of detail. A set of postcards featuring eight of my drawings is now available for £4.00, plus postage.

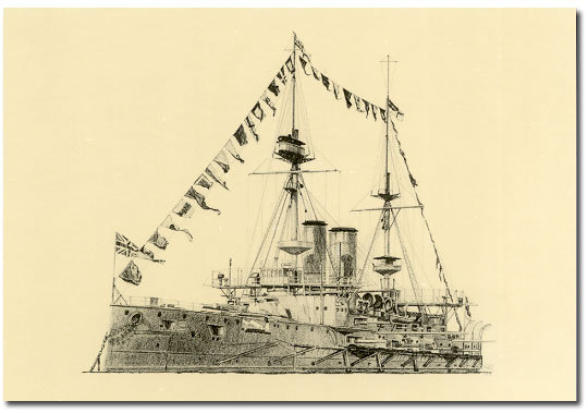

HMS Albemarle

First class battleship, laid down at Thames

Iron Works in July 1899, launched March

1901 and completed October 1903.

Albemarle was sold for breaking-up in

1920.

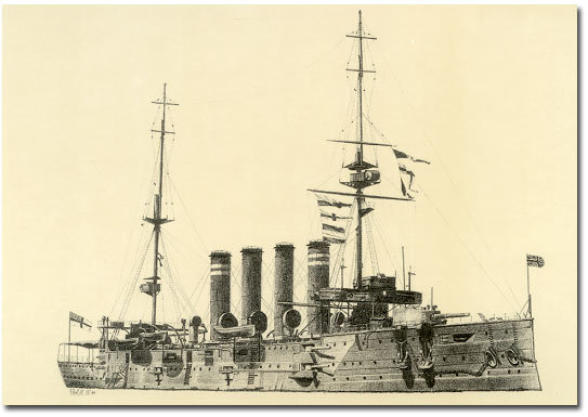

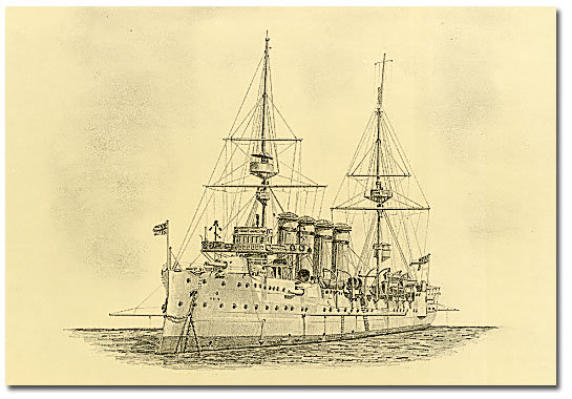

HMS Devonshire

First class armoured cruiser, laid own

at Chatham Dockyard in March 1902,

launched April 1904 and completed

August 1905. Main armament of four

7.5-inch guns; speed 22 knots.

Devonshire served throughout World

War One and was sold for breaking up

in 1921.

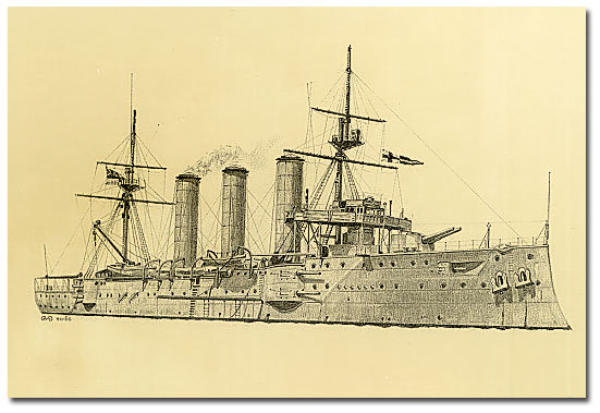

HMS Hogue

First class armoured cruiser, laid down

at Vickers Yard, Barrow in July 1898,

launched August 1900, and completed

November 1902. Hogue, together with

her sister ships Aboukir and Cressy was

sunk by the German submarine U-9 on

22 September 1914.

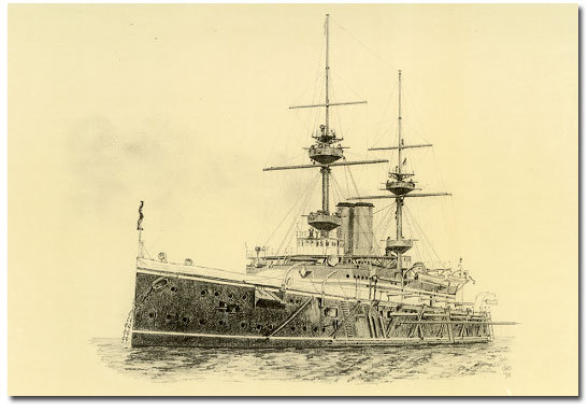

HMS Magnificent

First class battleship, laid down at

Chatham Dockyard in December

1893, launched December 1894 and

completed December 1895.

Magnificent was sold for breaking-up

in 1921.

HMS Commonwealth

First class battleship, laid down at

Fairfield's, Glasgow in June 1902,

launched May 1903 and completed

March 1905. Main armament of four

12-inch guns; speed 18.5 knots.

Served throughout World War One

and was sold for breaking up in 1921.

HMS Berwick

First class armoured cruiser, laid

down at Beardmores in Dalmuir

in April 1901, launched

September 1902, and completed

December 1903. Berwick served

throughout World War One and

was sold for breaking up in

1920.

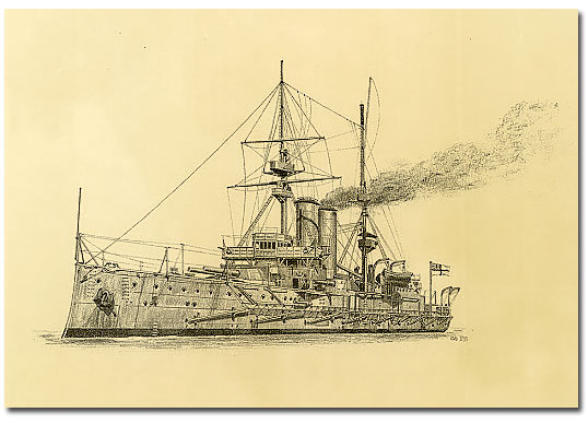

HMS London

First class battleship, laid down at

Portsmouth Dockyard in December

1898, launched September 1899

and completed June 1902. Main

armament of four 12-inch guns;

speed 18 knots. Served throughout

World War One and was sold for

breaking up in 1920. Pictured

above at the Coronation Naval

review of 1911.

The STRAITS Trilogy

Volume I: Superior Force : the conspiracy behind the escape of Goeben and Breslau Volume II: Straits : British Policy towards the Ottoman Empire and the Origins of the Dardanelles Campaign Volume III: The Millstone : British Naval Policy in the Mediterranean, 1900-1914, the Commitment to France and British Intervention in the WarSuperior Force

The Conspiracy Behind the Escape of Goeben and Breslau xxiii + 458 pages 20 illustrations 2 maps Full bibliography, notes and index Laminated card cover, 6¼"x9¼" ISBN 0 85958 635 9 Published 1996Straits

British Policy Towards the Ottoman Empire and the Origins of the Dardanelles Campaign xxvi + 604 pages 12 illustrations, 1 map Full bibliography, notes and index Laminated card cover, 5¾"x8¼" ISBN 0 85958 635 9 Hardcover ISBN 0 85958 663 4 Published 1997The Millstone

British Policy in the Mediterranean, 1900-1914, the Commitment to France and British Intervention in the War xv + 611 pages Full bibliography, notes and index Laminated card cover, 5¾"x8¼" ISBN 0 85958 690 1 Published 1999

This is the mobile variant of our web-site, specially designed for

viewing on smartphones, but lacking some of the more detailed

information available on our full-size site..

Views of Flamborough Head

Web-site design & content Copyright © 2019 Geoffrey Miller

These books provide a comprehensive account of British naval and

diplomatic policy in the two decades prior to the Great War,

focusing in particular on the escape of the German ships Goeben

and Breslau [Superior Force], the origins of the Dardanelles

Campaign [Straits], and the political and diplomatic imperatives

behind the British decision to enter the war in August 1914 [The

Millstone].

SMS Goeben

Superior Force

The Conspiracy Behind the Escape of

Goeben and Breslau

Synopsis : In the first weeks of August, 1914 the German battle cruiser, Goeben, and her accompanying light cruiser, Breslau, escaped the clutches of the pursuing British Mediterranean Squadron and took refuge at Constantinople, where they would later exert a decisive influence upon Turkey’s attempts to remain out of the war. In October 1914, with the connivance of the Turkish Minister of War, but against the wishes of the majority of the Turkish Cabinet, the German Admiral at the head of the Turkish Navy single-handedly forced the issue. At the helm of Goeben, Admiral Souchon manoeuvred into the Black Sea and deliberately shelled Russian ships, ports and shore installations. The Turks, reluctant to the last, were finally catapulted into the War. Yet, would this outcome have eventuated without the presence of Admiral Souchon and Goeben? The Turkish fleet by itself was too weak to risk a sortie in the Black Sea. Without Goeben could the issue have been forced? Meanwhile, the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, actively sought Greek co-operation for a planned major offensive against the Turks at the Dardanelles. His plea for assistance reached the British Officer at the head of the Greek Navy, Rear-Admiral Mark Kerr, who set impossible conditions which he knew would result in the proposal being rejected in London. What Churchill did not know, and which has never previously been revealed, was that Kerr had not only removed any chance of Greek participation at the Dardanelles, but had also been instrumental in the conspiracy afoot in Athens during August to allow the German ships to escape in the first place. Various accounts of the escape have sought to apportion blame, with the Admiralty (under Churchill), the Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean, and the Rear-Admiral, First Cruiser Squadron all being found culpable to some extent. What no previous account has revealed however is the fact that there was an organized conspiracy afoot in Athens, involving the Greek Premier on one side, and the King and a serving British Rear-Admiral on the other, to facilitate the escape of the German ships. The eventual destination of Goeben and Breslau (a mystery to the British until the ships actually reached the Dardanelles) was common knowledge amongst ruling circles in Athens some hours before Britain declared war on Germany. Privy to this secret was Rear-Admiral Mark Kerr, the British Officer at the head of the Greek Navy. For three vital days Kerr kept the secret to himself; then, when it was almost too late, he fed the Admiralty clues which were, however, not acted upon. In addition to being the most complete account of the dramatic escape yet published, Superior Force, for the first time, reveals the extent of the Athens conspiracy and the ambivalent rôle played by Mark Kerr who, soon after, would also remove any chance of Greek co-operation in the major offensive planned by Churchill against the Turks at the Dardanelles. Few men can genuinely be said to have changed history; by his actions in Athens in the summer of 1914 Mark Kerr is one of those few.

Straits

British Policy Towards the Ottoman Empire

and the Origins of the Dardanelles Campaign

Synopsis : On 19 February 1915 the guns of the massed Anglo-French fleet off Cape Helles opened fire on targets on the European and Asiatic shores of the Ottoman Empire. The Dardanelles campaign had begun. There is, however, little in-depth analysis of the way in which the campaign came about. Turkey’s pre-war alignment with Germany culminated with the signatures of the German Ambassador and Turkish Grand Vizier on the formal Treaty of Alliance on the afternoon of Sunday, 2 August 1914, but for months the treaty remained no more than a scrap of paper. The Turks mobilized only as fast as their moribund economy allowed while at the same time continuing to give the outward appearance of an anxious, if hardly disinterested, neutral. The menacing days of August passed; the Turks prevaricated, neither in the War nor immune from it. Unable to contain himself any longer, the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, actively sought Greek co- operation for a planned major offensive against the Turks at the Dardanelles. His plea for assistance reached the British Officer at the head of the Greek Navy, Rear-Admiral Mark Kerr, who set impossible conditions which he knew would result in the proposal being rejected in London. With his plans having thus gone awry, Churchill turned his gaze away from the plain of Troy — temporarily. By October, 1914 the patience of the Germans had also snapped. With the connivance of the Turkish Minister of War, but against the wishes of the majority of the Turkish Cabinet, the German Admiral at the head of the Turkish Navy single-handedly forced the issue. At the helm of the magnificent battle cruiser Goeben, which had escaped from the pursuing British Squadron in the first days of the war and had sought refuge at Constantinople, Admiral Souchon steamed into the Black Sea and deliberately shelled Russian ships, ports and shore installations. The Turks, reluctant to the last, were finally propelled into the war. Yet, would this outcome have eventuated without the presence of Souchon and Goeben? The Turkish fleet by itself was too weak to risk a sortie in the Black Sea. Without Goeben could the issue have been forced? Now that the Turks had become involuntarily embroiled in the War, Churchill’s eyes once more turned eastward. STRAITS takes the opening bombardment at the Dardanelles not as the starting point but as its culmination in an endeavour to explain how it was that Turkey was aligned with Germany — a ruinous alliance which was by no means preordained. British diplomatic policy towards the Ottoman Empire failed comprehensively when the result could have been so different. Why, for example, was every Turkish appeal for an alliance with Britain rebuffed? The Young Turk revolution of 1908 presented the British Foreign Office with a quandary — to support the new régime, which had successfully restored the constitution, or continue to remain aloof, as had been the policy during the reign of Abdul the Damned. Support was grudgingly provided but the improved British position at the Sublime Porte was jeopardized by two events: the new Ambassador, who was deeply antagonistic to the new régime, and the Anglo-Russian convention which meant that the British Foreign Secretary had to try somehow to support the Turks without alienating the Russians. The common thread running through the book is the struggle to control the Straits of the Dardanelles and Bosphorus from the period when the British Squadron at Malta commanded the Mediterranean Sea unopposed at the turn of the century through to the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire first as a result of the Turco-Italian and Balkan Wars and then following Turkey’s forced, and ultimately disastrous, entry into World War I. This struggle encompassed Russian aspirations, Greek ambition, French colonial ardour and British Imperial and oil considerations — all underpinned by the constant desire of the Turks themselves to prevent the collapse of their Empire. British diplomatic policy towards the Ottoman Empire failed comprehensively when the result could have been so different.

The Millstone

British Policy in the Mediterranean, 1900-

1914, the Commitment to France and British

Intervention in the War

Synopsis : At half past two on the afternoon of Sunday, 2 August 1914, Sir Edward Grey, the Foreign Secretary, informed the French Ambassador of the decision just reached by the British Cabinet — despite not yet being at war with Germany, if, nevertheless, the German High Seas Fleet ventured out from its base, the British fleet ‘would intervene … in such a way that from that moment Great Britain and Germany would be in a state of war.’ What led to the giving of this pledge? Was there an obligation on Britain’s part, or merely a commitment, moral or otherwise, to intervene in certain circumstances? The Foreign Secretary subsequently declared in his own defence that the promise to the French ‘did not pledge us to war.’ Grey was, however, wrong — once the promise was made, British entry into the war was certain. Despite this, a group within the Cabinet spent the afternoon of Sunday 2 August desperately searching for an issue around which they could group, and which would provide a more convenient excuse for British entry into the war than one based upon a moral commitment to France; that excuse was to be Belgian neutrality. Two things virtually guaranteed British entry in the war: the secret Anglo- French military and naval talks, which commenced in 1906, and the naval position in the Mediterranean. With Austria and Italy both constructing dreadnoughts, and facing the German naval challenge, British command of the Mediterranean could no longer be guaranteed. Similarly over- extended, the French were unable to protect both their Atlantic and Mediterranean coastlines. From strategic necessity came political expediency. The Millstone will show: • That Grey was more aware of what was settled by the secret military conversations than he pretended to be. • That the situation created by the German naval programme gave Britain no option other than to evacuate the Mediterranean. • That Anglo-French naval co-ordination and strategic planning remained chaotic. • That the Cabinet could not have prevented Britain’s entry into the war; all they could have done was to prevent the formation of a coalition Government. • That the pledge to France and consideration of British interests were the sole determinants of Britain’s entry. • That the German promise in August 1914 not to attack the French coast was irrelevant. • That, far from informing the German Government of the pledge given to Cambon as he claimed, Grey was determined to conceal this fact until Monday, 3 August. • That the issue of Belgian neutrality was used in August 1914 to assuage consciences and prevent the formation of a coalition Government, but was not crucial to the decision to intervene. • That the Continental policy, committing British troops to fight in Europe, was decided upon in August 1911 by a small inner circle of the Cabinet who knew precisely what it would entail.

Based on "Superior Force" the

acclaimed study of the escape of

Goeben and Breslau :

"The Traitor" is firmly grounded in fact. The majority of the people referred to in the novel took part in the actions described. Many of the conversations are based on diary entries, memoranda and letters subsequently published by the main protagonists. The principal exception to this is the character of Major Lionel Samson. When he first appears, Samson is, as he was in fact at the time, the British Military Consul at the siege of Adrianople in 1913. By 1915 he was, in real life, in charge of the allied espionage network based in Athens. However, between these two dates, all actions ascribed to him in The Traitor are fictional. On the other hand, the other main character, Admiral Mark Kerr is portrayed throughout as he was during the period. His actions, however implausible, are firmly based on the research gathered for my non-fiction studies of the events of this period, Superior Force, Straits and The Millstone. During the first week of August, 1914, Admiral Mark Kerr faced a desperate choice: betray his conscience or his country. It was a choice he faced in real life, where his attempt to reconcile the competing demands of his service to Britain and Greece failed. Major Lionel Samson’s principal experience of betrayal stemmed from a more personal encounter: an affair which ends when fate (according to Edith Roberts) intervenes. The sense of loss — and betrayal — Samson feels is heightened as, at that time, he does not believe in fate, or the pre- ordained workings of some exterior force, either for good or evil. Forced to reconsider his own deeply held beliefs, Samson is also disillusioned when everyone he encounters in Athens appears to operate on two different levels, and betrayal, at both personal and official levels, is rampant. Professor Geroulanos, for example, while certainly calling himself a Greek patriot, belongs to an organization whose only aim is the furtherance of German influence in his country (another example of the activities of a real-life character being mirrored in The Traitor). Even within the confines of the British Legation Samson comes to suspect that senior officials are hiding something. And, finally, the agent he employs is also working for someone else. Samson is forced to consider the prospect that the ability to betray, to lie at will, is part of man’s nature. Then, however, his life is saved by the same Professor Geroulanos he suspects of treason; his closest ally within the Legation is converted to share his suspicion regarding the Greek Premier; and his own agent, the Greek porter, posthumously provides the evidence to help resolve the final part of the puzzle — the identity of the traitor. Samson is almost re-converted into disbelieving the workings of a malign fate until a moment’s cowardice, which he later excuses by reasoning it was pre-ordained, results in his final test.

The Manor House

Accommodation, Books, Traditional Knitwear &

Hand-Knitted Ganseys, Breton shirts

Lesley Berry and Geoffrey Miller

The Manor House

Flamborough

Bridlington

East Riding of Yorkshire YO15 1PD

United Kingdom

Telephone: 01262 850943 (Mobile 07718

415234)

International: +44 1262 850943

E-mail: gm@flamboroughmanor.co.uk

The Manor House

Flamborough

Bridlington

East Riding of Yorkshire

Telephone

01262 850943

The Manor House, Flamborough, Bridlington, East Riding of Yorkshire. YO15 1PD

Telephone: 01262 850943 [International: +44 1262 850943]

E-mail: gm@flamboroughmanor.co.uk

Web-site design & content Copyright © 2025 Geoffrey Miller